Trump COVID 19 Begin

Steady leadership at any time is important, but especially during a crisis. In early 2020, the world slowly came to the realization that there was a new very serious coronavirus health threat, what would become known as COVID 19.

Countries were not prepared and struggled to deal with the outbreak. We all learned the phrase “flatten the curve” in reference to slowing down the pandemic’s contagious spread.

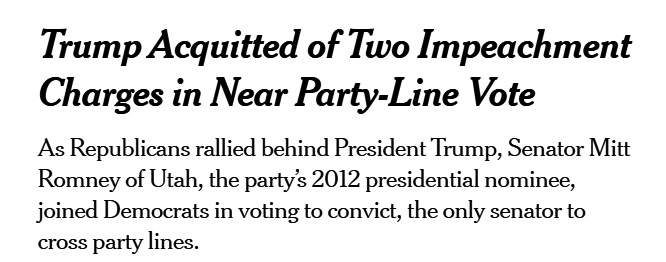

President Trump’s leadership was often lacking. He denied that there was a problem and when he could no longer deny the problem he diminished its threat and when he could no longer diminish its threat he blamed others–the media in particular as always–for the threat.

Here is a timeline of Trump and COVID 19. See my first of several COVID 19 pandemic posts for a much expanded timeline.

China origin

It was in December 2019 that the as yet unnamed deadly virus’s impact was first observed.

December 6: according to a study in The Lancet, the symptom onset date of the first patient identified was “Dec 1, 2019 . . . 5 days after illness onset, his wife, a 53-year-old woman who had no known history of exposure to the market, also presented with pneumonia and was hospitalizein the isolation ward.” In other words, as early as the second week of December, Wuhan doctors were finding cases that indicated the virus was spreading from one human to another.

December 21: Wuhan doctors begin to notice a “cluster of pneumonia cases with an unknown cause.”

Trump COVID 19 Begin

Vaping vs Coronavirus

Trump more interested in vaping

January 18: Health and Human Services Secretary Alex M Azar had his first discussion about the virus with President Trump. Unnamed “senior administration officials” told the Washington Post that “the president interjected to ask about vaping and when flavored vaping products would be back on the market.”

Trump COVID 19 Begin

Totally Under Control

January 22: President Trump, in an interview with CNBC at the World Economic Forum in Davos, Switzerland, declared, “We have it totally under control. It’s one person coming in from China. We have it under control. It’s going to be just fine.”

January 24:In a tweet, Trump praised China for its efforts to prevent the spread of the virus. “China has been working very hard to contain the Coronavirus. The United States greatly appreciates their efforts and transparency. It will all work out well. In particular, on behalf of the American People, I want to thank President Xi!” [NPR timeline]

Trump COVID 19 Begin

January 29: Dr. Mike Ryan, head of the WHO’s Health Emergencies Programme, said, “The whole world needs to be on alert now. The whole world needs to take action and be ready for any cases that come from the epicenter or other epicenter that becomes established.” [NPR timeline]

January 29, 2020: on April 7, 2020, the NY Times reported that top White House adviser Peter Navarro had warned in a memo to Trump administration officials that the coronavirus crisis could cost the United States trillions of dollars and put millions of Americans at risk of illness or death.

“The lack of immune protection or an existing cure or vaccine would leave Americans defenseless in the case of a full-blown coronavirus outbreak on U.S. soil,” Navarro’s memo said. “This lack of protection elevates the risk of the coronavirus evolving into a full-blown pandemic, imperiling the lives of millions of Americans.”

The memo came during a period when Mr. Trump was playing down the risks to the United States. He later went on to say that no one could have predicted such a devastating outcome.

In one worst-case scenario cited in the memo, more than a half-million Americans could die.

WHO declaration

January 30: the World Health Organization Amid officially declared a “public health emergency of international concern.”

That same day, Trump addressed the coronavirus during a speech on trade in Michigan.

“We think we have it very well under control,” Trump said. “We have very little problem in this country at this moment — five — and those people are all recuperating successfully. But we’re working very closely with China and other countries, and we think it’s going to have a very good ending for us.”

“Hopefully it won’t be as bad as some people think it could be,” he added.

And at a campaign rally in Iowa, Trump talked about the U.S. partnership with China to control the disease. “We only have five people. Hopefully, everything’s going to be great. They have somewhat of a problem, but hopefully, it’s all going to be great. But we’re working with China, just so you know, and other countries very, very closely. So it doesn’t get out of hand.” [NPR timeline]

January 31: Trump blocked travel from China.

February 2: Trump told Fox News host Sean Hannity, “We pretty much shut it down coming in from China.”

February 10: at a campaign rally in Manchester, N.H., Trump said: “Looks like by April, you know, in theory, when it gets a little warmer, it miraculously goes away. I hope that’s true. But we’re doing great in our country. China, I spoke with President Xi, and they’re working very, very hard. And I think it’s going to all work out fine.” [NPR timeline]

February 13: in an interview with Geraldo Rivera, Trump characterized the threat of the virus in the U.S. by saying: “In our country, we only have, basically, 12 cases, and most of those people are recovering and some cases fully recovered. So it’s actually less.” [NPR timeline]

Trump COVID 19 Begin

Very Small

February 14: China reports that 1,716 health workers have contracted COVID-19 and that six of them have died.

Trump discussed the “very small” number of U.S. coronavirus cases with Border Patrol Council members:

“We have a very small number of people in the country, right now, with it. It’s like around 12. Many of them are getting better. Some are fully recovered already. So we’re in very good shape.”

Centers for Disease Control Director Robert Redfield had estimated that the “virus is probably with us beyond this season and beyond this year.” Despite that view, President Trump continued to push the idea that it would be gone in a matter of weeks.

“There’s a theory that, in April, when it gets warm, historically, that has been able to kill the virus,” he said . “So we don’t know yet. We’re not sure yet. But that’s around the corner.”

Trump COVID 19 Begin

Under Control

February 23: Speaking to reporters on the White House lawn, President Trump stated that “We have it very much under control in this country.”

Stock Market crashes

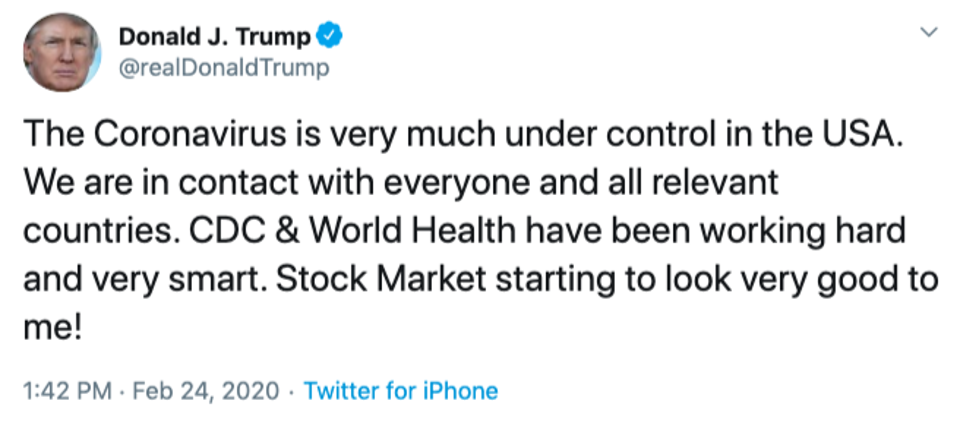

February 24: stock market plummeted as Dow Jones Industrials fell more than 1,000 points.

The same day, Trump asked for $1.25 billion in emergency aid. It grows to $8.3 billion in Congress.

He tweeted that the virus “is very much under control” and the stock market “starting to look very good to me!”

Trump COVID 19 Begin

Pence Put In Charge

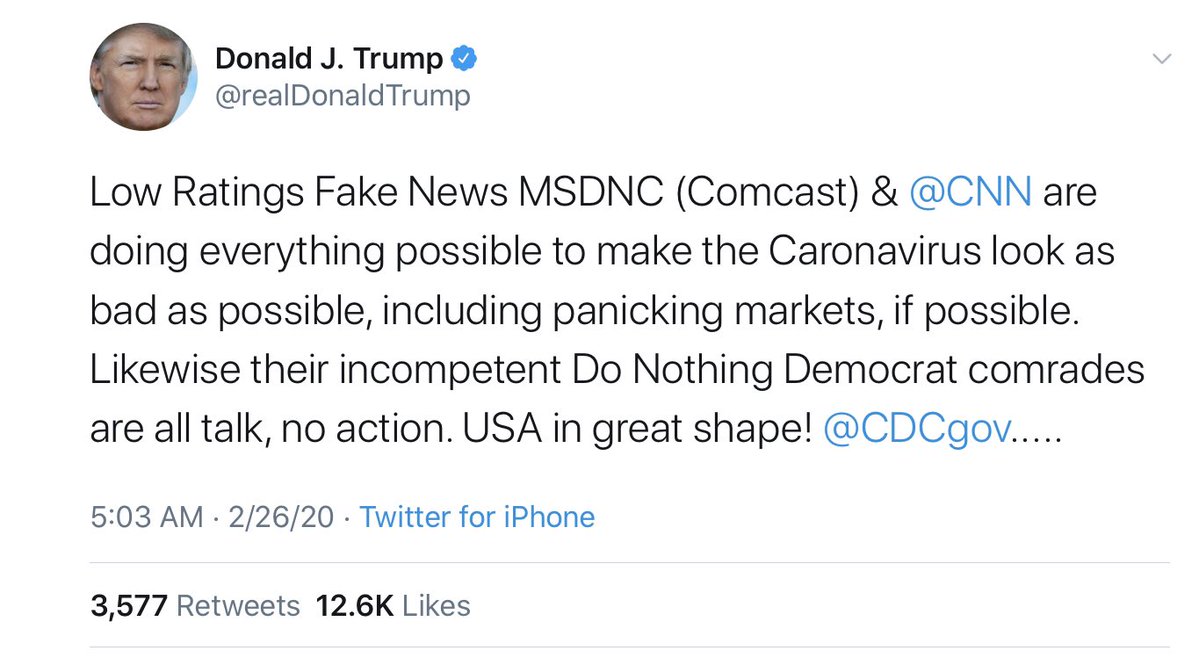

February 26: In a news conference that day, Trump said the United States was “really prepared.”

He also said, ““When you have 15 people, and the 15 within a couple of days is going to be down to close to zero, that’s a pretty good job we’ve done.”

He put Vice President Mike Pence in charge of the White House task force.

Trump also criticized the media and accused them of creating the crisis and that all was fine. [NPR timeline]

He added during a brief press conference: “We’re going to be pretty soon at only five people,” he said. “And we could be at just one or two people over the next short period of time. So we’ve had very good luck.”

“I think every aspect of our society should be prepared,” he added later. “I don’t think it’s going to come to that, especially with the fact that we’re going down, not up. We’re going very substantially down, not up.”

February 27: the number of infections globally continued to grow. There were 3,474 cases of COVID-19 — including 54 deaths — outside of China in 44 countries.

President Trump stated, “It’s going to disappear. One day — it’s like a miracle — it will disappear.”

Trump COVID 19 Begin

First American Death

February 29: a patient near Seattle became the first coronavirus patient to die in the United States.

While speaking at the Conservative Political Action Conference, Trump again claimed his administration had the coronavirus under control.

“I’ve gotten to know these professionals. They’re incredible,” Trump said. “And everything is under control. I mean, they’re very, very cool. They’ve done it, and they’ve done it well. Everything is really under control.”

It would be revealed later that a CPAC attendee tested positive for COVID-19, leading multiple Republican lawmakers who came into contact with him to self-quarantine.

Trump COVID 19 Begin

- COVID 19 Pandemic Begins

- February 2020 COVID 19

- March 2020 COVID 19

- April 2020 COVID 19

- May 2020 COVID 19

- Trump COVID 19 Continue

- April 2020 Trump COVID

- June 2020 COVID 19

- July 2020 COVID 19

- August 2020 COVID 19

- September 2020 COVID 19

- October 2020 COVID 19

- November 2020 COVID 19

- December 2020 COVID 19

- Winter 2021 COVID 19

- Spring 2021 COVID 19

- Summer 2021 COVID 19

- Fall Winter 2021 COVID