War Hero Deborah Sampson

Early life

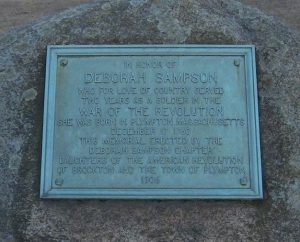

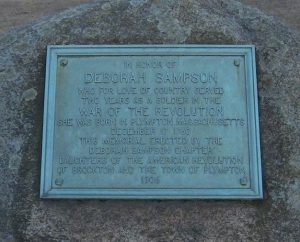

Deborah Sampson was born on December 17, 1760 in Plympton, Massachusetts. Her father, Johnathan Sampson, Jr. was a direct descendant of the Mayflower pilgrim Miles Standish. Her mother, Deborah Bradford, was a direct descendant of the Mayflower pilgrim, William Bradford.

Though having historic roots, the Sampson family suffered financially due to bad luck and poor skills on Johnathan Samson’s part. He eventually abandoned his wife and seven children.

War Hero Deborah Sampson

Indentured servant

Because of her difficult situation and in poor health, Mrs Sampson placed her children in the homes of various relatives and friends. Ten-year-old Deborah Sampson became an indentured servant until her release at the age of 18.

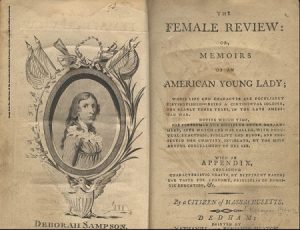

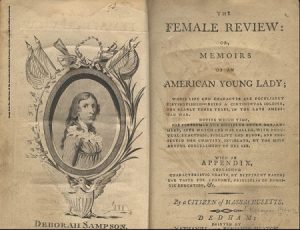

For the next three years, she worked part-time as a schoolteacher and worked in homes spinning and weaving. Turning 21, above average in height strong, and hearing of the Revolutionary War’s heroics, Deborah was looking for adventure. She decided to dress like a man and join the Continental Army.

After her first attempt, she thought others were suspicious and left.

Abner Weston, a neighbor of Sampson, wrote in his diary about her cross-dressing: “Their hapend a uncommon affair at this time, for Deborah Samson of this town dress her self in men’s cloths and hired her self to Israel Wood to go into the three years Servis. But being found out returnd the hire and paid the Damages.”

Sampson tried again, this time successfully joining the Fourth Massachusetts Regiment on May 20, 1782 under the alias Robert Shurtliff, Her five feet seven inch height helped fool others.

War Hero Deborah Sampson

Battle of Tarrytown

Less that two months later, on July 3, 1782 at the Battle of Tarrytown, Sampson was wounded . Two musket balls hit her in the thigh and a sabre cut her forehead.

Fearful that others would discover her true identity, she begged her fellow soldiers to let her die and not take her to the hospital, but they refused to abandon her. Doctors treated her head wound, but she left the hospital before they could attend to the thigh.

She removed one of the balls herself with a penknife and sewing needle, but her leg never fully healed because the other musket ball was too deep for her to reach.

Almost a year later, on April 1, 1783, Sampson was transferred to Philadelphia as a personal orderly to General John Patterson. This job entitled her to a better quality of life, better food, less danger, and improved shelter, but during that summer, Sampson came down with fever.

War Hero Deborah Sampson

Dr Barnabas Binney

Dr Barnabas Binney cared for her. He saw the cloth she used to bind her breasts and so discovered her secret. He did not betray her; he took her to his house, where his wife and daughters housed and took care of her.

In September, after Sampson had fully recovered, Binney asked her to deliver a personal letter to General Patterson. Upon delivering it, Patterson informed her that the letter said she was a woman in disguise.

War Hero Deborah Sampson

Discharge and marriage

On October 23, 1783 Deborah Sampson was honorably discharged from the Army.

On April 7, 1785 she married Benjamin Gannet from Sharon, Massachusetts. Together they had three children, Earl, Mary, and Patience.

War Hero Deborah Sampson

Request for pay

In January 1792 Deborah Sampson petitioned the Massachusetts State Legislature for pay which the army had withheld from her because of her sex. Her petition passed through the State Senate, was approved, and signed by Governor John Hancock. The General Court of Massachusetts verified her service and wrote that she “exhibited an extraordinary instance of female heroism by discharging the duties of a faithful gallant soldier, and at the same time preserving the virtue and chastity of her gender, unsuspected and unblemished“. The award was 34 pounds.

War Hero Deborah Sampson

Pension request

Twelve years later, on February 20, 1804 Paul Revere wrote to Massachusetts US Representative William Eustis on behalf of Sampson. Revere requested that the US Congress grant her a military pension. This had never before been requested by or for a woman, but with her health failing and her family destitute, the money was greatly needed. Revere wrote, “I have been induced to enquire her situation, and character, since she quit the male habit, and soldiers uniform; for the more decent apparel of her own gender…humanity and justice obliges me to say, that every person with whom I have conversed about her, and it is not a few, speak of her as a woman with handsome talents, good morals, a dutiful wife, and an affectionate parent.“

More than a year later, on March 11, 1805, the US Congress obliged Revere’s letter and placed her on the Massachusetts Invalid Pension Roll. This pension plan paid Deborah Sampson four dollars a month.

Continuing to experience financial difficulty, in 1809, Sampson sent another petition to Congress, asking that her pension as an invalid soldier, given to her in 1804, commence with the time of her 1793 discharge. Had her petition been approved, she would have been awarded $960, to be divided into $48 a year for twenty years. However, Congress denied the request.

Seven years later, Sampson’s petition came before Congress again. This time, they approved it awarding her $76.80 a year. With this amount, she was able to repay all her loans and take better care of the family farm.

War Hero Deborah Sampson

Death

On April 29, 1827 Deborah Sampson died at the age of 66. She is buried in Rock Ridge Cemetery in the town of Sharon, Massachusetts.

In 1831, Sampson’s husband petitioned Congress for pay as the spouse of a deceased soldier. Although the couple was not married at the time of her service, in 1837 the committee concluded that the history of the Revolution “furnished no other similar example of female heroism, fidelity and courage.” He was awarded the money, though he died before receiving it.

War Hero Deborah Sampson

Proclamation

May 23, 1983: Governor Michael J. Dukakis signed a proclamation which declared that Deborah Sampson was the Official Heroine of the Commonwealth of Massachusetts. Two news services stated this was the first time in US history that any state had proclaimed anyone as the official hero or heroine.

Using her unselfish example today, it was reported on March 21, 2017 in the Military Times that “advocates are lobbying for sweeping reforms in women veterans services in the wake of a nude photo sharing scandals that have raised questions about misogyny and morale in the military.

“When people think of veterans, when they close their eyes, they don’t think about someone who looks like me,” said Allison Jaslow, chief of staff for Iraq and Afghanistan Veterans of America. “Until we get over that hurdle, we’re not going to be able to get everything else that we need.”

The measure — dubbed the Deborah Sampson Act, after the woman who disguised herself as a man to serve in the Continental Army — mandates more peer-to-peer counseling for women veterans, expanded newborn care services at Department of Veterans Affairs facilities, better tracking of women’s health issues by the department and $20 million to retrofit VA medical centers with more privacy features.

Deborah Sampson Act

On January 5, 2021, President Trump signed H.R. 7105, the “Johnny Isakson and David P. Roe, M.D. Veterans Health Care and Benefits Improvements Act of 2020.

The American Legion reported that, “One of the bill’s most notable provisions is the Deborah Sampson Act, which paves the way to improving care for women veterans within the Veterans Health Administration (VHA). The act will establish an Office of Women’s Health within VHA to oversee women’s health programs. The office will be responsible for ensuring standards of care for women veterans are being met by the VHA. The bill mandates that every Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) health-care facility has a women’s health primary care provider.”

War Hero Deborah Sampson

Shere Hite was born on November 2, 1942 in St Joseph, Missouri. MO. She died in London as a German citizen on September 9, 2020.

Shere Hite was born on November 2, 1942 in St Joseph, Missouri. MO. She died in London as a German citizen on September 9, 2020.