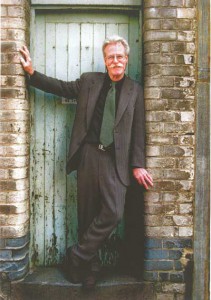

Edward Chip Monck

Celebrating his birthday, March 5, 1939

The above audio clip is from an interview with Chip Monck in 2009 on the 40th Anniversary of the Woodstock Festival. Glenn A Baker interviewed Monck as part of the Ovation Channel show ‘Monday Night Legends’

The chipmonck.com site starts with these questions:

- Have you heard of Woodstock?

- Monterey Pop?

- The Rolling Stones Tour?

- Newport Jazz and Folk Festivals?

- The Concert for Bangladesh?

And then answers those questions with this simple answer:

He staged them all

Edward Chip Monck

Chip Monck

Edward Herbert Beresford “Chip” Monck was born in Wellesley, Massachusetts. He became a lighting and staging designer, but as the above references suggest, he did those things for some of the most iconic musical events of the 20th century.

When he was 20, Monck began working at the Greenwich Village nightclub The Village Gate. While at the gate, his young friend Bobby Dylan worked in Monck’s basement apartment. Reputedly, Dylan wrote “A Hard Rain’s a’Gonna Fall” and “The Ballad of Hollis Brown” there.

Monck recalls about Dylan, “He spied the IBM Selectric [typewriter]. He typed while I worked at the Gate. That gave him like six hours, he’d just drift in, I gave him a key and he’d sit down and type and then I’d come back in and he’d go, or we’d go and have a drink or something. We really never spoke much.”

Edward Chip Monck

Festivals

While still working at the Village Gate, Monck also began working with the Newport Folk Festival, and the Newport Jazz Festival.

If those credentials aren’t enough, in 1967 he lit the Monterey International Pop Festival where Jimi Hendrix’s American coming out party occurred.

He also worked with Bill Graham in renovating Graham’s Fillmore theaters.

Edward Chip Monck

Woodstock Music and Art Fair

Woodstock Ventures hired Monck to do the lighting at their Fair. The last minute change of venue from Wallkill, NY to Bethel, NY forced Monck to eliminate much of his planned lighting. Spotlights became the primary source.

But to those who attended the Woodstock Music and Art Fair, Chip Monck’s voice along with John Morris’s became the reassuring threads that connected each band. Both men took turns not just introducing performers, but giving advice, recommending choices, and explaining what was going on at a time when social media didn’t exist as a term.

Perhaps the most famous quote of that weekend was Monck’s: ““The warning that I’ve received, you might take it with however many grains of salt you wish, that the brown acid that is circulating around is not specifically too good. It is suggested that you stay away from that. But it’s your own trip, be my guest. But please be advised that there’s a warning, okay?”

Edward Chip Monck

A LOT more after Woodstock

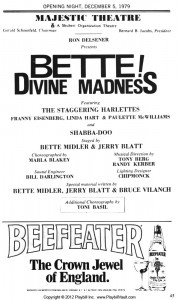

For years he helped light Rolling Stone tours and he received Tony nominations in lighting for The Rocky Horror Show and Bette Midler’s Divine Madness.

He was always busy working many major venues. In 1989 he helped set up Pope John Paul’s papal mass at L.A.’s Dodger Stadium.

In the early 90s, Monck moved to Australia, his wife’s home country, where he continued in the lighting and design business. (Monck’s wife died in 2002)

Edward Chip Monck

Honors

He continues to live Melbourne, his focus mainly on corporate and retail work. In 2003, he received the Parnelli Lifetime Achievement Award. The award recognizes pioneering, influential professionals and their contributions, honoring both individuals and companies. It is the Oscar of the live event industry.Here is the video that introduced that presentation.