November 21 Peace Love Art Activism

Feminism

Lucy Burns

November 21, 1913: Lucy Burns fined $1 for chalking the sidewalk in front of the White House. (see Dec 8)

Suffragists Lucy Burns and Dora Lewis

November 21, 1917: Occoquan jail officials began force-feeding Lucy Burns and Dora Lewis followed by Elizabeth McShane. Unable to pry open Burns’s mouth, officials inserted a glass tube up her nostril, causing significant bleeding and pain. McShane developed stomach ulcers and gall bladder infection. [Herstory article] (see Nov 27 – 28)

Rebecca L. Felton

November 21, 1922: Rebecca L. Felton of Georgia was sworn in as the first woman to serve in the U.S. Senate. (see April 2, 1923)

November 21 Peace Love Art Activism

School Desegregation

November 21, 1927: first adopted in 1890 following the end of Reconstruction, the Mississippi Constitution divided children into racial categories of Caucasian or “brown, yellow, and black,” and mandated racially-segregated public education. In 1924, the state law was applied to bar Martha Lum, a nine-year-old Chinese American girl, from attending Rosedale Consolidated High School in Bolivar County, Mississippi, a school for white students. Martha’s father, Gong Lum, sued the state in a lawsuit that did not challenge the constitutionality of segregated education but instead challenged his daughter’s classification as “colored.”

When the Mississippi Supreme Court held that Martha Lum could not insist on being educated with white students because she was of the “Mongolian or yellow race,” her father appealed to the United States Supreme Court.

On November 21, 1927, in Gong Lum v Rice, the Supreme Court ruled against the Lums and upheld Mississippi’s power to force Martha Lum to attend a colored school outside the district in which she lived. Applying the “separate but equal” doctrine established in 1896’s Plessy v. Ferguson decision, the Court held that the maintenance of separate schools based on race was “within the constitutional power of the state legislature to settle, without intervention of the federal courts.” The Court thus reasoned that Mississippi’s decision to bar Ms. Lum from attending the local white high school did not violate the Fourteenth Amendment because she was entitled to attend a colored school. This decision extended the reach of segregation laws and policies in Mississippi and throughout the nation by classifying all non-white individuals as “colored.” (see September 18, 1945)

November 21 Peace Love Art Activism

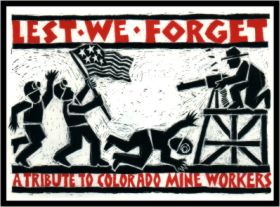

US Labor History

Columbine Massacre

November 21, 1927: six miners striking for better working conditions under the IWW banner were killed and many wounded in the Columbine Massacre at Lafayette, Colo. Out of this struggle Colorado coal miners gained lasting union contracts. (see May 18, 1928)

César E. Chávez, Dolores Huerta, and the UFW

November 21, 2000: The United Farm Workers union ended its 16-year-old boycott of California table grapes. The union’s co-founder, César Chávez, who died in 1993, had called for the boycott in 1984 to focus on the spraying of dangerous pesticides. ”Some goals of that boycott have already been met,” the union’s president, Arturo Rodriguez, said in a letter. ”César Chávez’s crusade to eliminate use of five of the most toxic chemicals plaguing farm workers and their families has been largely successful.” The union also held two boycotts against California table grapes in the 1960’s and 1970’s. (see April 23, 2003)

November 21 Peace Love Art Activism

FREE SPEECH

November 21, 1938: The Library Bill of Rights originated on this day with the Des Moines, Iowa, Public Library. The statement was a response to the anti-Semitic actions by Nazi Germany, which included excluding Jews and books written by Jews from libraries. (see June 19, 1939)

November 21 Peace Love Art Activism

Japanese Internment Camps

November 21, 1945: Manzanar, one of the Relocation Centers (usually referred to as concentration camps) in the evacuation and internment of the Japanese-American during World War II, was officially closed on this day. See February 19, 1942 for President Roosevelt’s Executive Order authorizing the program. Many historians regard the evacuation and internment of the Japanese-Americans as the greatest civil liberties tragedy in American history. The government’s program was officially ended on December 17, 1944, but Manzanar did not close until this day, almost a year later. The site was designated a National Historic Site, on March 3, 1992, and is now managed by the National Park Service. (see Internment for expanded chronology)

November 21 Peace Love Art Activism

November 21 Music et al

George Harrison deported

November 21, 1960: from his Anthology: It was a long journey on my own on the train to the Hook of Holland. From there I got the day boat. It seemed to take ages and I didn’t have much money – I was praying I’d have enough. I had to get from Harwich to Liverpool Street Station and then a taxi across to Euston. From there I got a train to Liverpool. I can remember it now: I had an amplifier that I’d bought in Hamburg and a crappy suitcase and things in boxes, paper bags with my clothes in, and a guitar. I had too many things to carry and was standing in the corridor of the train with my belongings around me, and lots of soldiers on the train, drinking. I finally got to Liverpool and took a taxi home – I just about made it. I got home penniless. It took everything I had to get me back. (see Dec 5)

“Stay” by Maurice Williams and the Zodiacs

November 21 – 27, 1960: “Stay” by Maurice Williams and the Zodiacs #1 Billboard Hot 100. Williams wrote the song in 1953 when he was 15 after unsuccessfully trying to convince his girlfriend to ignore her 10 o’clock curfew. The original recording of “Stay” remains the shortest single ever to reach the top of the American record charts, being only 1 minute and 37 seconds long.

LSD

November 21, 1965: not the first “acid test” but a similar event held six days before the Santa Cruz Acid Test, was the Lysergic A Go Go, staged by Hugh Romney (later Wavy Gravy) and Del Close. Not as participatory as the Pranksters’ Tests, attendees “brought their own head,” recalled Romney. “We did not supply any psychotropics,” Gravy says. “What we provided was a palette.”

Though they distributed “solar meat cream” capsules at the door, according to a Los Angeles Free Press report, they were merely filled with “Safeway hamburger.” The light show was provided by Romney’s roommate, Del Close. The Lysergic A Go Go was a genuinely chaotic happening, crammed with some 500 heads. (see Nov 27)

John & Yoko

November 21, 1968: Yoko Ono suffered a miscarriage of the baby she was expecting with John Lennon. It had been due to be born in February. Lennon stayed at her side at Queen Charlotte’s Hospital, London, sleeping overnight next to her. When that bed was needed for a patient he slept on the floor. Just before the miscarriage, the fetal heartbeat was recorded. It was included in Lennon and Ono’s 1969 album Life With The Lions, followed by two minutes’ silence. The child was named John Ono Lennon II, and was buried in a secret location. It was later claimed that Ono’s miscarriage was caused by the stress of their October drugs bust and subsequent arrest.(Beatles, see Nov 22; Life, see May 9, 1969)

Beatles’ Anthology 1

November 21, 1995: The Beatles’ Anthology 1 released in the U.S. The double CD contained 60 songs. (next Beatles, see Dec 9)

November 21 Peace Love Art Activism

BLACK HISTORY

November 21, 1964: the FBI mailed an anonymous letter to Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King containing recordings of King engaging in what the FBI regarded as extramarital sexual activity. The letter was part of the FBI’s attempt to “neutralize” King as a civil rights leader, a strategy it adopted as an official plan on December 23, 1963. The recordings on the tape were derived from secret and illegal surveillance of King by the FBI using listening devices placed in hotel rooms and other locations where the FBI knew King would be. The FBI had installed the first bug on January 5, 1964.

While Attorney General Robert Kennedy approved wiretaps on King on October 10, 1963, he did not approve the use of the far more intrusive “bugs.” The letter and the tape recording sent to King has been sealed by a judge, and it is not publicly available. (BH see Nov 29; MLK, see Dec 1)

SCOTTSBORO TRAVESTY

November 21, 2013: the State of Alabama posthumously pardoned Haywood Patterson, Charles Weems and James A. Wright, the three black men who had been falsely convicted more than 80 years ago in the rapes of two white women, thus absolving the last of the so-called Scottsboro Boys. During a hearing in Montgomery, the Alabama Board of Pardons and Paroles voted unanimously to issue pardons to the three men. (see Scottsboro for expanded chronology)

November 21 Peace Love Art Activism

Vietnam

November 21, 1967: Gen. William Westmoreland, commander of U.S. Military Assistance Command Vietnam, told U.S. news reporters: “I am absolutely certain that whereas in 1965 the enemy was winning, today he is certainly losing.”

With such reassurances, the ferocity of the Tet attacks only two months later stunned Americans. [CFR article] (see Nov 29)

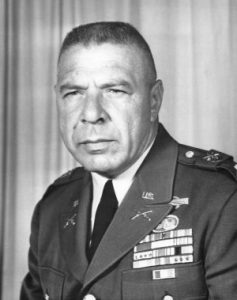

Colonel “Bull” Simons

November 21, 1970: a combined Air Force and Army team of 40 Americans–led by Army Colonel “Bull” Simons–conducted a raid on the Son Tay prison camp, 23 miles west of Hanoi, in an attempt to free between 70 and 100 American suspected of being held there. The raid was conducted almost flawlessly, but no prisoners of war were found in the camp. They had been moved earlier to other locations. (see January 12, 1971)

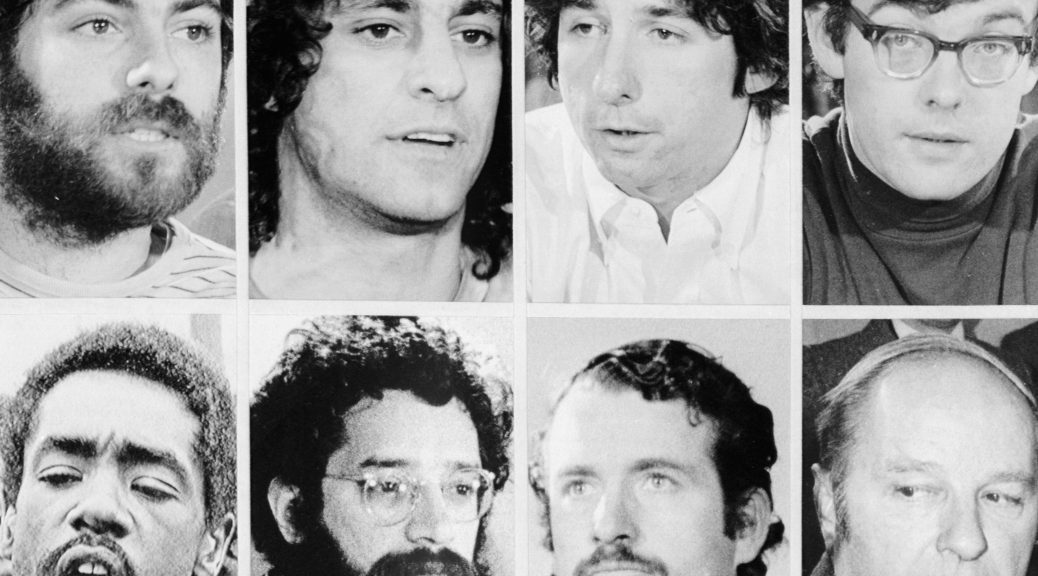

Chicago 8

November 21, 1972: all of the convictions were reversed by the US Court of Appeals for the Seventh Circuit on the basis that the judge was biased in his refusal to permit defense attorneys to screen prospective jurors for cultural and racial bias. (NYT article) (see Nov 23)

November 21 Peace Love Art Activism

Native Americans

Alcatraz Takeover

November 21, 1970: the Indians occupying Alcatraz began their second year on the island in San Francisco Bay today, still determined to get the United States to deed it to them for an Indian culture center. (NA, see Nov 26; Alcatraz, see June 12, 1971)

Code Talkers

November, 21, 2013: 96-year-old Edmond Harjo and other American Indian “code talkers” were formally awarded the Congressional Gold Medal to using their native language to outwit the enemy and protect U.S. battlefield communications during World Wars I and II. (see Nov 26)

November 21 Peace Love Art Activism

Watergate Scandal

November 21, 1973: President Richard Nixon’s attorney, J. Fred Buzhardt, revealed the existence of an 18 1/2-minute gap in one of the White House tape recordings related to Watergate. (NYT article) (see Watergate for expanded chronology)

November 21 Peace Love Art Activism

DEATH PENALTY

November 21, 1974: the National Conference of Catholic Bishops spoke out against capital punishment in a reversal of the traditional Roman Catholic Church position supporting the death penalty as a legitimate means of self-protection for the state. (see July 2, 1976)

November 21 Peace Love Art Activism

Iran–Contra Affair

November 21, 1986,: National Security Council member Oliver North and his secretary, Fawn Hall, started shredding documents that implicated them in selling weapons to Iran and channeling the proceeds to help fund the Contra rebels in Nicaragua. (see Nov 25)

November 21 Peace Love Art Activism

The Cold War

Dissolution of Yugoslavia

November 21, 1995: leaders of Croatia, Bosnia and Serbia agreed to the Dayton Accords ending nearly four years of terror and ethnic bloodletting that had left a quarter of a million people dead in the worst war in Europe since World War II. The Accords were formally signed in Paris, France on December 14. (see Dec 14)

NATO expanded

November 21, 2002: NATO invited seven former communist countries to join the alliance: Slovenia, Slovakia, Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania, Romania and Bulgaria. [RFE article] (see February 19, 2008)

Gen. Ratko Mladic

November 21, 2017: Gen. Ratko Mladic, the former Bosnian Serb commander, was convicted of genocide, crimes against humanity and war crimes. He was sentenced to life in prison.

From 1992 to 1995, the tribunal found, Mr. Mladic, 75, was the chief military organizer of the campaign to drive Muslims, Croats and other non-Serbs off their lands to cleave a new homogeneous statelet for Bosnian Serbs.

The deadliest year of the campaign was 1992, when 45,000 people died, often in their homes, on the streets or in a string of concentration camps. Others perished in the siege of Sarajevo, the Bosnian capital, where snipers and shelling terrorized residents for more than three years, and in the mass executions of 8,000 Muslim men and boys after Mladic’s forces overran the United Nations-protected enclave of Srebrenica. [BBC article] (see Yugoslavia for expanded chronology)

November 21 Peace Love Art Activism

Sexual Abuse of Children

November 21, 2003: Ohio state Judge Richard Niehaus of Common Pleas Court found the Archdiocese of Cincinnati guilty of failing to report sexually abusive priests in the 1970’s and 80’s and imposed the maximum penalty possible, a fine of $10,000. (NYT article) (see February 27, 2004)

November 21 Peace Love Art Activism

Consumer Protection

November 21, 2007: officials announced the recall of more than a half-million pieces of Chinese-made children’s jewelry contaminated with lead. [TC article] (see February 5, 2014)

November 21 Peace Love Art Activism

SEPARATION OF CHURCH AND STATE

November 21, 2011: in the Republican race for the 2012 Republican presidential nomination, Rick Santorum, former U.S. Senator from Pennsylvania, based his campaign on his strong Christian views.

On this day, he said that the U.S. should be governed by “God’s law.” His position was characteristic of many fundamentalist Christians and their political leaders who believed that religious doctrine — which is to say, their view of what it says — was a higher law than the Constitution and the Bill of Rights. (see May 5, 2014)

November 21 Peace Love Art Activism

LGBTQ

November 21, 2013: the Pentagon had ordered national guard facilities nationwide to extend equal treatment to married couples in the U.S. military – including same-sex married couples – and Defense Secretary Chuck Hagel gave them a December 1 deadline to comply. Rather than comply, Gov. Mary Fallin of Oklahoma’s announced that Oklahoma will stop processing all military spouse benefit applications at state-owned National Guard facilities rather than begin accepting the applications from same-sex spouses. Instead, military spouse applications, including those of same-sex couples, will only be accepted at four federally owned National Guard bases: the Air National Guard bases in Tulsa and Oklahoma City, the Regional Training Institute in Oklahoma City and Camp Gruber. (see Nov 27)

November 21 Peace Love Art Activism

TERRORISM

November 21, 2013: officials arrested Pamela Morris, 45, the former secretary of the KKK chapter, for committing perjury before a grand jury investigating a 2009 cross burning her son, Stephen, is being investigated about. (see Nov 29)

November 21 Peace Love Art Activism

Immigration History

November 21, 2017: District Judge William H. Orrick in San Francisco issued an injunction to permanently block President Trump’s executive order to deny funding to cities that refused to cooperate with federal immigration officials, after finding the order unconstitutional.

Orrick’s came in response to a lawsuit filed by the city of San Francisco and nearby Santa Clara County and followed a temporary halt on the order that the judge issued in April.

Orrick, in his summary of the case, found that the Trump administration’s efforts to move local officials to cooperate with its efforts to deport undocumented immigrants violated the separation of powers doctrine as well as the Fifth and Tenth amendments.

“The Constitution vests the spending powers in Congress, not the President, so the Executive Order cannot constitutionally place new conditions on federal funds. Further, the Tenth Amendment requires that conditions on federal funds be unambiguous and timely made; that they bear some relation to the funds at issue; and that they not be unduly coercive,” the judge wrote. “Federal funding that bears no meaningful relationship to immigration enforcement cannot be threatened merely because a jurisdiction chooses an immigration enforcement strategy of which the President disapproves.” [WP article] (IH, see Nov 29; Trump restrictions, see Dec 4)

November 21 Peace Love Art Activism

Nuclear/Chemical News

November 21, 2017: Russia’s meteorological service reported “extremely high pollution” of a radioactive isotope in the Urals near a facility that previously suffered the third worst nuclear catastrophe in history. This was the first time that the Russians admitted to any issues.

The news bolstered international November 9 report that a ruthenium-106 leak originating in the Urals sent a radioactive cloud over Europe. Greenpeace Russia said it would ask the prosecutor general to investigate the possible cover-up of a nuclear accident.

Rosatom, Russia’s state nuclear company, said in a statement to The Telegraph there had been “no unreported accidents” and the ruthenium-106 emission was “not linked to any Rosatom site”. Its Mayak facility, where an explosion on September 29, 1957 contaminated a swath of central Russia, told state news agency RIA Novosti that it had not processed nuclear fuel with ruthenium-106 in 2017.[Telegraph article]

Terrorism vulnerability

November 21, 2017: officials with the Nuclear Regulatory Commission announced a three-month investigation at Millstone Nuclear Power Plant in Waterford, CT had found that a contract security guard there failed to follow proper procedures regarding testing weapons used for the facility’s security and then falsified records to hide what had happened.

The investigation determined the officer deliberately failed to perform his assigned duties, including being responsible for the accountability, testing and maintenance of weapons used to respond to terrorist attacks. Investigators also found numerous discrepancies on a number of weapons maintenance records between January 2015 and June 2016, according to Sheehan.

Specifically, the officer indicated in records that test-firing, cleaning or maintenance activities had been performed on weapons. But in reality, the weapons had not been worked on, and in some cases, had not been retrieved from their staged locations. [ctpost article] (NN and T, see Nov 28)

November 21 Peace Love Art Activism

Trump Impeachment Inquiry/Public

November 21, 2019: in her opening statement, the former top Russia expert on the National Security Council Fiona Hill called for Republicans to stop propagating what she called a “fictional narrative” that Ukraine, not Russia, meddled in the 2016 elections. She called the conspiracy claim a story invented by Russian intelligence services to destabilize the United States and deflect attention from their own culpability.

David Holmes, who worked in the United States Embassy in Kyiv told lawmakers that he overheard President Trump, who was speaking loudly, asking Ambassador Sondland whether Ukraine President Zelensky was “going to do the investigation.” Sondland told Trump that Zelensky “loves your ass,” and would conduct the investigation and do “anything you ask him to,”

According to Holmes’s account, Sondland later told him that Trump cared only about “big stuff that benefits the president” like the “Biden investigation” into the son of former Vice President Joseph R. Biden Jr. Mr. Sondland largely confirmed that account on Wednesday but said he did not recall specifically mentioning Mr. Biden. [NYT story] (see TII/P for expanded coverage)

November 21 Peace Love Art Activism

Environmental Issues/Space

November 21, 2020: a SpaceX Falcon 9 rocket launched the Sentinel-6 Michael Freilich satellite, an advanced ocean-mapping satellite into orbit for NASA and the European Space Agency.

Built by Airbus in Germany, the satellite was roughly the size of a small pickup truck and carried multiple instruments to track changes in sea level down to just a few centimetres. To measure sea levels, they’ll beam electromagnetic signals down to the world’s oceans and then measure how long it takes for them to bounce back.

The oceanography satellite was named for Michael Freilich, the former head of NASA’s Earth science division. [Space.com article] (next EI, see Nov 25; next Space, see January 24, 2021)