John Lennon Opines Jesus

July 29, 1966

August 1966 interview about his March opinion

John Lennon Opines Jesus

Looking for trouble

By 1966, it could seem that the whole world knew who Beatles were and that most of the world liked their music and them, too. Of course there were many who did not like the Beatles’s music nor the Beatles themselves. Critics made wise cracks about them needing a haircut, looking like girls, their looks in general.

Rock and Roll was just a teenager and there were plenty of people who were suspicious of the music and anyone associated with it. The Red Scare and McCarthyism of the 1950s still echoed in the early 60s, the Soviet Union was still our arch nemesis, and the re-invigorated civil rights movement threatened the status quo, however unjust that status quo was.

Parents warned their teenagers, “If you go looking for trouble, you’ll find it.” Teenagers knew, “If you want to find a reason to dislike my music, you’ll find a reason.”

John Lennon Opines Jesus

Maureen Cleave

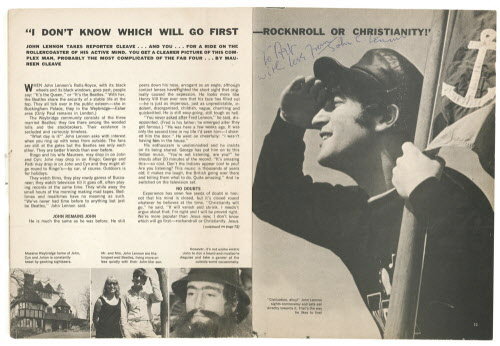

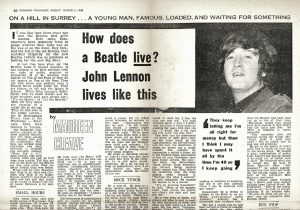

Journalists knew that a Beatle interview was money in the bank. Maureen Cleave, of the London Evening Standard, ran a series of interviews called “How does a Beatle Live?”

On March 4, 1966, Maureen Cleave interviewed John Lennon for the series.

During the interview, Lennon, who had been reading about various religions said, “Christianity will go. It will vanish and shrink. I needn’t argue about that. I’m right and I’ll be proved right. We’re more popular than Jesus now. I don’t know which will go first, rock ‘n’ roll or Christianity. Jesus was all right but his disciples were thick and ordinary. It’s them twisting it that ruins it for me.”

The article appeared and that was that. No outrage by the British.

John Lennon Opines Jesus

US reaction

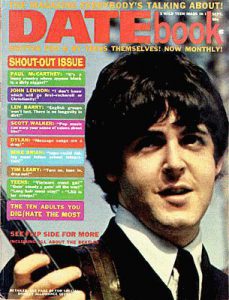

Tony Barrow was the Beatles press officer. He offered the rights to all four interviews to US teen magazine, Datebook.

On July 29, 1966 the article appeared with a headline featuring the Lennon Christianity quote, which was only a small part of the entire interview.

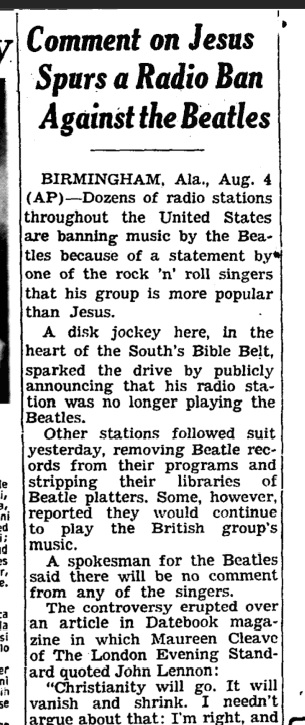

It became national news on August 4. A NY Times article lead sentence read: “Dozens of radio stations throughout the United States are banning music by the Beatles because of a statement by one of the rock ‘n’ roll singers that his group is more popular than Jesus.”

The article’s last sentence read: “Several radio stations scheduled bonfires for the burning of Beatle records and pictures.”

John Lennon Opines Jesus

Some support

The US negative reaction was not universal. A Kentucky radio station declared that it would give the Beatles’ music airplay to show its “contempt for hypocrisy personified”, and the Jesuit magazine America wrote: “Lennon was simply stating what many a Christian educator would readily admit.”

John Lennon Opines Jesus

Aftermath

The Beatles toured that summer, but it was their last. While the Christianity comment alone did not cause that cessation, it was a part of it.

And in 2008, the Vatican issued the following statement: “The remark by John Lennon, which triggered deep indignation, mainly in the United States, after many years sounds only like a ‘boast’ by a young working-class Englishman faced with unexpected success, after growing up in the legend of Elvis and rock and roll. The fact remains that 38 years after breaking up, the songs of the Lennon-McCartney brand have shown an extraordinary resistance to the passage of time, becoming a source of inspiration for more than one generation of pop musicians.” [BBC article]