American Hero Medgar Evers

July 2, 1925 – June 12, 1963

From an NAACP article: Medgar Evers was a native of Decatur, Mississippi, attending school there until being inducted into the U.S. Army in 1943. Despite fighting for his country as part of the Battle of Normandy, Evers soon found that his skin color gave him no freedom when he and five friends were forced away at gunpoint from voting in a local election. Despite his resentment over such treatment, Evers enrolled at Alcorn State University….

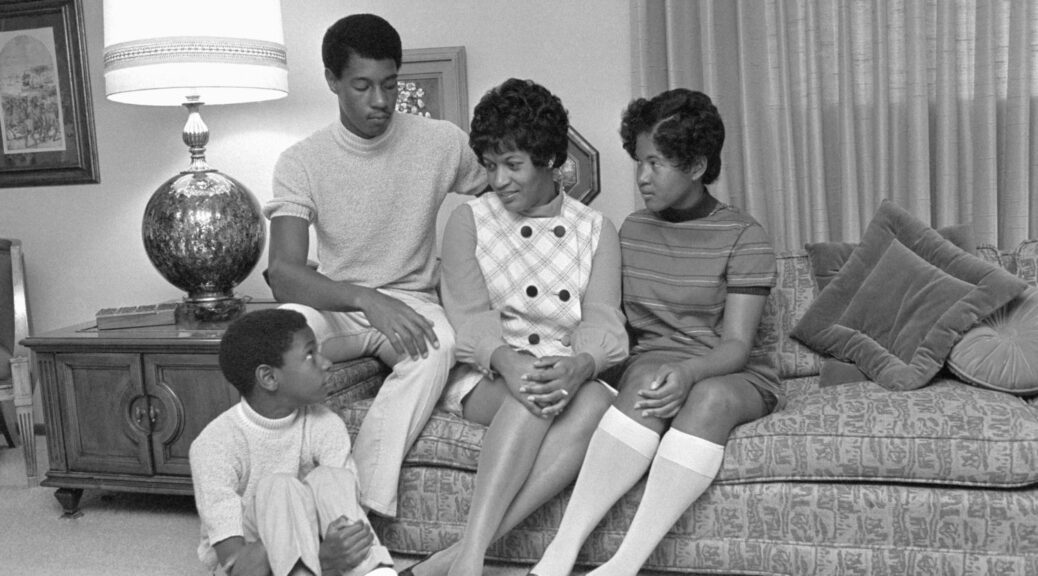

He married classmate Myrlie Beasley on December 24, 1951, and completed work on his degree the following year. The couple moved to Mound Bayou, MS, where T.R.M. Howard had hired him to sell insurance for his Magnolia Mutual Life Insurance Company. Howard was also the president of the Regional Council of Negro Leadership (RCNL), a civil rights and pro self-help organization….

After moving to Jackson, he was involved in a boycott campaign against white merchants and was instrumental in eventually desegregating the University of Mississippi when that institution was finally forced to enroll James Meredith in 1962.

…Evers found himself the target of a number of threats… On May 28, 1963, a molotov cocktail was thrown into the carport of his home, and…he was nearly run down by a car after he emerged from the Jackson NAACP office.

American Hero Medgar Evers

June 12, 1963

On June 12, 1963, Byron De La Beckwith assassinated NAACP civil rights leader Medgar Evers outside his home.

Byron De La Beckwith was born on November 9, 1920. He would die on January 21, 2001, 37 years, 7 months, 10 days after he gunned down Evers. He was a member of the White Citizens’ Council.

The arc of justice was a long and serpentine one. Here is a chronology of the days, months, years, and decades following the assassination.

American Hero Medgar Evers

1963

June 15, 1963: mourners file past the open casket of Medgar Evers in Jackson, Mississippi.

June 23, 1963: the FBI announced the arrest in Greenwood, MS of Byron De La Beckwith.

June 26, 1963: the federal government dropped its civil rights charges against De La Beckwith in view of Mississippi’s plans to prosecute him for Evers’s murder. On July 2, 1963: in Jackson, Mississippi, the Hinds County grand jury indicted Beckwith.

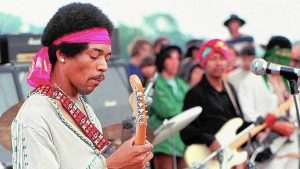

July 6, 1963: Dylan first performed “Only a Pawn in Their Game” at a voter registration rally in Greenwood, Mississippi. The song refers to the murder of Medgar Evers. He would sing it again at the March on Washington on August 28.

Took Medgar Evers’ blood

A finger fired the trigger to his name

A handle hid out in the dark

A hand set the spark

Two eyes took the aim

Behind a man’s brain

But he can’t be blamed

He’s only a pawn in their game.

“You got more than the blacks, don’t complain

You’re better than them, you been born with white skin, ” they explain

And the Negro’s name

Is used, it is plain

For the politician’s gain

As he rises to fame

And the poor white remains

On the caboose of the train

But it ain’t him to blame

He’s only a pawn in their game.

And the marshals and cops get the same

But the poor white man’s used in the hands of them all like a tool

He’s taught in his school

From the start by the rule

That the laws are with him

To protect his white skin

To keep up his hate

So he never thinks straight

‘Bout the shape that he’s in

But it ain’t him to blame

He’s only a pawn in their game.

And the hoofbeats pound in his brain

And he’s taught how to walk in a pack

Shoot in the back

With his fist in a clinch

To hang and to lynch

To hide ‘neath the hood

To kill with no pain

Like a dog on a chain

He ain’t got no name

But it ain’t him to blame

He’s only a pawn in their game.

They lowered him down as a king

But when the shadowy sun sets on the one

That fired the gun

He’ll see by his grave

On the stone that remains

Carved next to his name

His epitaph plain

Only a pawn in their game

American Hero Medgar Evers

Pleads not guilty

July 8, 1963: De La Beckwith pleaded not guilty in State Circuit Court and on July 25 he entered a state mental institution for court-ordered mental tests. On August 10 a state judge ordered him released and transferred to jail to await trial.

January 27, 1964: the Mississippi State prosecution accepted a full slate of white men to sit as a jury in the case of Byron De La Beckwith.

February 5, 1964: De La Beckwith took the witness stand in his defense and said he did not kill Evers.

February 7, 1964: a Jackson, Mississippi jury reported that it could not reach a verdict, resulting in a mistrial. The jury Was 7-5 for acquittal.

Phil Ochs had already released his composition “Ballad of Medgar Evers.

In the state of Mississippi many years ago

A boy of 14 years got a taste of southern law

He saw his friend a hanging and his color was his crime

And the blood upon his jacket left a brand upon his mind

Chorus: too many martyrs and too many dead

Too many lies too many empty words were said

Too many times for too many angry men

Oh let it never be again.

His name was Medgar Evers and he walked his road alone

Like Emmett till and thousands more whose names we’ll never know

They tried to burn his home and they beat him to the ground

But deep inside they both knew what it took to bring him down

The killer waited by his home hidden by the night

As Mstepped out from his car into the rifle sight

He slowly squeezed the trigger, the bullet left his side

It struck the heart of every man when Evers fell and died.

And they laid him in his grave while the bugle sounded clear

Laid him in his grave when the victory was near

While we waited for the future for freedom through the land

The country gained a killer and the country lost a man

American Hero Medgar Evers

Second Trial

April 6, 1964: Byron De La Beckwith went on trial for the second time. Again there was an all-white jury.

On April 11, the day after ten crosses were burned in the Jackson, Mississippi area, 75 KKK members showed up as spectators at the trial.

Capt. Ralph Hargrove of the Jackson Police Department testified that the fingerprint found on the rifle that killed Medgar Evers was De La Beckwith’s.

April 18, 1964: a second mistrial was declared in the murder case against De La Beckwith and on November 14 William L Walter, the district attorney who had prosecuted the case announced that Beckwith would not be tried a third time unless new evidence was obtained.

January 12, 1966: De La Beckwith appeared before a Congressional committee and refused to answer charges that he had participated in Ku Klux Klan intimidation since his release from jail.

American Hero Medgar Evers

Louisiana bomb

September 27, 1973: New Orleans police arrested De La Beckwith who had a time-bomb and several rifles in his car. He stated he had come to New Orleans to sell china. Police stated that De La Beckwith intended to blow up the home of A I Botnick, head of the New Orleans chapter of B’nai B’rith. It was the first day of Rosh Hashanah. Botnick had moved his family out of New Orleans several days earlier after receiving threatening calls.

October 11, 1973: the Louisiana Ku Klux Klan said it was raising a defense fund for De La Beckwith.

January 19, 1974: Byron De La Beckwith was found not guilty of carrying a live time bomb and a pistol on a midnight drive into New Orleans from Mississippi.

Beckwith said he was “exceedingly grateful for the kind treatment I have received and I ask the blessing of the most high God on all who have shown me such consideration.”

Beckwith had stated during the trial that he did not know he was carrying a time bomb into New Orleans. He said that the was “astounded” to learn from newspaper accounts after his arrest that there was a bomb in his car.

May 16, 1975: a Louisiana state jury convicted Byron De La Beckwith of transporting a dynamite bomb to New Orleans without a permit. The earlier trial had been a federal one.

On August 1, De La Beckwith, Mississippi was sentenced to five years in prison.

American Hero Medgar Evers

15 more years

October 1, 1989: sealed documents from the Mississippi Sovereignty Commission revealed that at the same time that the state of Mississippi prosecuted De La Beckwith for the murder of Evers, another arm of the state, the Mississippi Sovereignty Commission, secretly assisted Beckwith’s defense, trying to get him acquitted. The revelation led the district attorney’s office to reopen and re-prosecute the case against Beckwith. It was the first of a series of prosecutions of unpunished killings from the civil rights era.

December 17, 1990: De La Beckwith, now 70 years old was arrested as a fugitive from Mississippi. Officials said a grand jury in Hinds County had heard testimony the previous week in the slaying of Medgar Evers.

December 19, 1990: twenty-seven years after the slaying, authorities charged De la Beckwith with Evers’s murder for the third time. Prosecutors said that they had turned up new evidence and new witnesses after a 14-month investigation.

In a hearing in Tennessee, where Beckworth had lived for the past nine years, Beckwith denied killing Evers and vowed to resist extradition “tooth, nail and claw.”

American Hero Medgar Evers

Tennessee

December 31, 1990: in a move intended to speed his transfer from Tennessee to Mississippi, De la Beckwith was arrested on a governor’s warrant charging him with first-degree murder and was jailed without bond.

January 14, 1991: Chattanooga, TN. Judge Joe DeRisio of Hamilton County Criminal Court ordered that De la Beckwith be returned to Mississippi to face a charge of first-degree murder in the 1963 slaying of Medgar Evers, but DeRisio delayed putting the extradition order into effect until January 22 to give De La Beckwith time to file an appeal with the Tennessee Court of Criminal Appeals.

June 3, 1991: the Tennessee Court of Criminal Appeals ruled that De la Beckwith must be returned to Mississippi to stand trial a third time.

September 30, 1991: Nashville, TN. The Tennessee State Supreme Court ruled that De la Beckwith must be extradited to Mississippi to stand trial a third time. Mr. Beckwith’s lawyer then took the case to the Federal courts, asking for a temporary restraining order to block the extradition. Tennessee agreed to hold Mr. Beckwith until then.

October 3, 1991: a Federal judge in Chattanooga, Tenn., refused to block the extradition of De la Beckwith, sending him back to Mississippi for a third trial.

American Hero Medgar Evers

Mississippi Must Decide

November 13, 1991: Jackson, Miss. Judge L. Breland Hilburn of Hinds County Circuit Court denied bond to Byron De La Beckwith and ordered him to remain in jail pending his murder trial.

August 4, 1992: Judge, Hilburn refusedDe La Beckwith’s request to let him go free because of deteriorating health and memory.

August 24, 1992: the Mississippi Supreme Court delayed indefinitely the third trial . The court said it would decide later if the state may prosecute De La Beckwith in the now 29-year-old case. Beckwith’s lawyers had asked the court to review a lower court’s refusal to dismiss the murder charge, which they say violated Beckwith’s right to a speedy trial and due process.

December 16, 1992: a divided Mississippi Supreme Court refused to block the trial of De La Beckwith. The court voted 4 to 3 to deny Mr. Beckwith’s claim that the case should be dismissed without going to trial.

December 23, 1992: a Mississippi state judge reversed an earlier order and set bond at $100,000 for De La Beckwith. He was freed later after a benefactor who did not want to be identified came forward with $12,000 cash required for his release, said a defense lawyer, Merrida Coxwell.

American Hero Medgar Evers

Trial #3

January 26, 1994: a jury of eight blacks and four whites was chosen. [NYT article]

February 1, 1994: the prosecution wound up dramatically with two more witnesses testifying that the defendant had bragged about the killing. Mark Reiley was the sixth person to testify that De La Beckwith had boasted of or made reference to having killed Evers in 1963.

February 2, 1994: the defense in the third trial of Byron De La Beckwith began its presentation much the same way its counterparts did at the first trial 30 years ago: calling witnesses who placed the defendant 95 miles away at the time of the shooting. Two witnesses, a businessman and auxiliary police officer from the town of Greenwood by the name of Roy Jones, who had died, and a retired Greenwood police lieutenant, Hollis Cresswell, were heard through the reading of the transcript of their testimony at the first trial in 1964.

American Hero Medgar Evers

11,197 days later

February 5, 1994: after six hours of deliberation a jury of eight blacks and four whites unanimously convicted Byron de la Beckwith of murder and immediately sentenced to life in prison.

December 22, 1997: The Mississippi Supreme Court upheld the conviction. The court said the 31-year lapse between the ambush slaying and Beckwith’s conviction did not deny him a fair trial.

January 21, 2001: De La Beckwith, 80 years old, died at University Medical Center in Jackson, Mississippi. [NYT article]

American Hero Medgar Evers

USNS Medgar Evers (T-AKE-13)

October 10, 2009: Myrlie Evers-Williams, the widow of the slain civil rights pioneer Medgar Evers, heard Navy Secretary Ray Mabus, a former Mississippi governor, announce that he was naming a new Navy supply ship for her husband. She said: “I think of those who will serve on this ship and those who will see it in different parts of the world. And perhaps they, too, will come to know who Medgar Evers was and what he stood for.”

American Hero Medgar Evers

American Hero Medgar Evers

Evers home

Landmark

January 11, 2017: the National Park Service named the Evers home a national historic landmark.

Monument

March 12, 2019: the Evers home became a national monument. The federal government took over the three-bedroom, ranch-style home from Tougaloo College, a historically black institution that had maintained the Evers home since 1993, when the property was donated to the school by the Evers family.

Disregarded

March 15, 2019: Congressional Black Caucus chairwoman Karen Bass of California said Mississippi’s Republican Gov. Phil Bryant was “clearly despicable” for not acknowledging work by Rep. Bennie Thompson, the state’s only black congressman, to get the Evers’s home named a national monument.

On Twitter, Gov Bryant had praised President Trump and Mississippi’s two Republican U.S. senators for the monument designation.

Thompson tweeted back: “Give adequate credit. I’ve worked on this for 16 years.”

Disregarded and dismissed

In June 2025, Defense Secretary Pete Hegseth, President Trump’s Defense Secretary, directed the secretary of the Navy to rename several ships, including the USNS Medgar Evers.