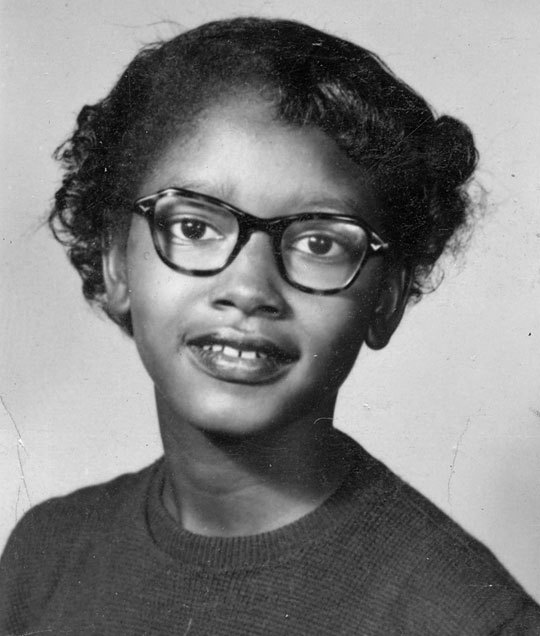

Civil Rights Activist Claudette Colvin

In February 2017, the City of Montgomery, Alabama passed a proclamation naming March 2 “Claudette Colvin Day.”

Civil Rights Activist Claudette Colvin

15-year-old student

On March 2, 1955, Claudette Colvin was a 15-year-old student at Booker T. Washington High School in Montgomery, Alabama. Her family did not own a car, so she used buses to get back and forth to school. Annie Larkins Price was a friend.

On their way home from school together that March day, Price recalled, “The bus was getting crowded and I remember him (the bus driver) looking through the rear view mirror asking her to get up out of her seat, which she didn’t. She didn’t say anything. She just continued looking out the window. She decided on that day that she wasn’t going to move.“

Other black passengers complied; Colvin ignored the driver.

Civil Rights Activist Claudette Colvin

Police summoned

“I’d moved for white people before,” Colvin says. But this time, she was thinking of the slavery fighters she had read about recently during Negro History Week in February. “The spirit of Harriet Tubman and Sojourner Truth was in me. I didn’t get up.” “They dragged her off that bus,” said Price, who was sitting behind her classmate. “The rest of us stayed quiet. People were too scared to say anything.” Colvin screamed that her Constitutional rights were being violated. (Colvin arrest report)

We all know the name of Rosa Parks who also defied the Jim Crow laws separating Blacks and Whites throughout the United States. The Courts called it “separate but equal.” We know Parks for her refusal to give up her seat and the resulting 381-day Montgomery bus boycott that followed under the leadership of the young Rev. Martin Luther King, Jr.

That was nine months later on December 1, 1955.

Civil Rights Activist Claudette Colvin

Browder v Gayle

In the meantime, court had ruled against Colvin and put her on probation. She became one of the plaintiffs in the Browder v. Gayle case, along with Aurelia S. Browder, Susie McDonald, and Mary Louise Smith (Jeanatta Reese, who was initially named a plaintiff in the case, withdrew early on due to outside pressure).

On June 13, 1956, the federal court ruled that Montgomery’s segregated bus system was unconstitutional. In December 1956, the city of Montgomery passed an ordinance allowing any bus passenger to sit in any seat they chose to.

Two years later, Colvin moved to New York City, where she worked as a nurse’s aide at a Manhattan nursing home. She retired in 2004.

Civil Rights Activist Claudette Colvin

In a 2013 interview…

Colvin stated, “I tell—one of the questions asks, “Why didn’t you get up when the bus driver asked you, and the policemen?” I say, “I could not move, because history had me glued to the seat.” And they say, “How is that?” I say, “Because it felt like Sojourner Truth’s hands were pushing me down on one shoulder and Harriet Tubman’s hands were pushing me down on another shoulder, and I could not move. And I yelled out, ’It’s my constitutional rights,’” because I wasn’t breaking a law under the state’s law, separate but equal; I was sitting in the area that was reserved for black passengers.

At that time, we didn’t even want to be called “black,” because black had a negative connotation. We were called “coloreds.” So I was sitting in the coloreds’ section. But because of Jim Crow law, the bus driver had police force, he could ask you to get up. And the problem was that the white woman that was standing near me, she wasn’t an elderly white woman. She was a young white woman. She had a whole seat to sit down by—opposite me, in the opposite row, but she refused to sit down; because of Jim Crow laws, a white person couldn’t sit opposite a colored person. And a white person had to sit in front of you.

The purpose was to make white people feel superior and colored people feel inferior”.

Civil Rights Activist Claudette Colvin

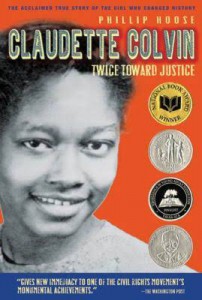

Book

In 2009, Farrar, Straus and Giroux published Claudette Colvin: Twice Toward Justice by Phillip Hoose. Here is a link to an excerpt from that book: NPR story

From Twice Toward Justice, here is Colvin’s description of the police who came onto the bus that March 2 day:

One of them said to the driver in a very angry tone, “Who is it?” The motorman pointed at me. I heard him say, “That’s nothing new . . . I’ve had trouble with that ‘thing’ before.” He called me a “thing.” They came to me and stood over me and one said, “Aren’t you going to get up?” I said, “No, sir.” He shouted “Get up” again. I started crying, but I felt even more defiant. I kept saying over and over, in my high-pitched voice, “It’s my constitutional right to sit here as much as that lady. I paid my fare, it’s my constitutional right!” I knew I was talking back to a white policeman, but I had had enough.

One cop grabbed one of my hands and his partner grabbed the other and they pulled me straight up out of my seat. My books went flying everywhere. I went limp as a baby—I was too smart to fight back. They started dragging me backwards off the bus. One of them kicked me. I might have scratched one of them because I had long nails, but I sure didn’t fight back. I kept screaming over and over, “It’s my constitutional right!” I wasn’t shouting anything profane—I never swore, not then, not ever. I was shouting out my rights.

In September 2016, the National Museum of African-American History and Culture opened to great fanfare. Colvin was not invited to the opening dedication and the Museum did not recognize her act of bravery.

References

yes yes this is the stuff i want to hear!!!

Hopefully you’ll find more that you want to hear here.