Dyer Anti-Lynching bill

Abraham Lincoln’s Republican Party

Abraham Lincoln’s Republican Party casts a long shadow in American history. While today’s GOP does not emphasize inclusion in its platform, for decades after the Civil War Lincoln’s party tried to give actual freedom to the legally freed Black population in the southern States. The Democratic party in those states gradually regained control, created Black Codes, and became an increasingly important piece of the national Democratic party’s evolving success.

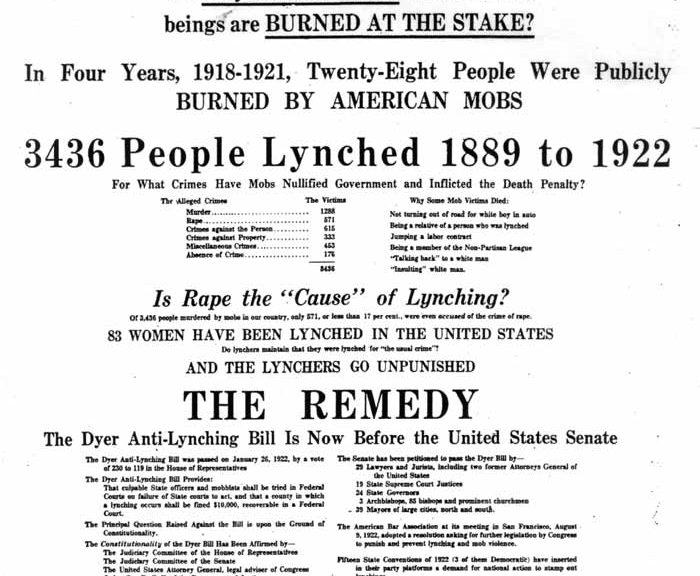

On the face of it, introducing a bill in the early 20th century that made lynching a federal crime seems a sure thing.

It was not.

Dyer Anti-Lynching bill

Leonidas C. Dyer

Missouri’s Leonidas C. Dyer served 11 terms in the U.S. Congress from 1911 to 1933. He had served in the Spanish-American War in 1898 entering as a private and rising to the rank of colonel.

Dyer was both a Republican and a progressive, terms that today seem antithetical. The 1917 race riots in Missouri as well as the continual reports of lynchings in the south brought him to the point of introducing the Dyer Anti-Lynching Bill in April 1918 .

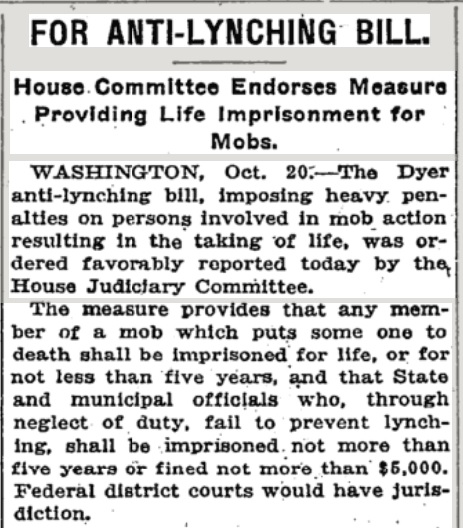

It called for the prosecution of lynchers in federal court and that State officials who failed to protect lynching victims or prosecute lynchers could face five years in prison and a $5,000 fine. The victim’s heirs could recover up to $10,000 from the county where the crime occurred.

In 1920 the Republican Party supported such legislation in its platform from the National Convention.

Dyer Anti-Lynching bill

No official record

Here is a look at the long and frustrating path the bill took. Keep in mind that according to the site, Chestnutt Archieve, there had been thousands of lynchings that had taken place in the United States since 1882! Like police shootings today, there was no official record kept of such killings. More than 70% of the lynchings were done by Whites against Blacks. Those Whites lynched (also by Whites) were done typically when the White person was perceived as having aided a Black person in some way.

Dyer Anti-Lynching bill

House Judiciary Committee

October 20, 1921: the House Judiciary Committee supported the bill.

October 26, 1921: President Warren G. Harding spoke at the 50th Anniversary celebration of the founding of Birmingham, Alabama. Before a crowd of about 100,000 whites and African-Americans, he gave a strong civil rights message: “Let the black man vote when he is fit to vote; prohibit the white man voting when he is unfit to vote.” Reportedly his statement was greeted with complete silence.

Dyer Anti-Lynching bill

Representative Finis Garrett of Tennessee

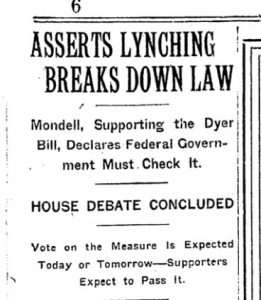

December 20, 1921: although outnumbered in the House membership by more than two to one, Democrats under the leadership of Representative Finis Garrett of Tennessee filibustered successfully against consideration of the Dyer Anti-Lynching bill. Republican floor leader, Rep Franklin Mondell, gave in to the filibuster and agreed to postpone debate on the the bill until after the Christmas holidays.

January 4, 1922: debate on the Dyer anti-lynching bill got under way in the House. Democratic House leader, Representative Garrett of Tennessee, spent three hours demanding roll calls in an attempt to postpone debate.

January 26, 1922: after more than three weeks, the House passed the Dyer Bill by a vote of 230 to 119.

Dyer Anti-Lynching bill

Senate Committee on the Judiciary

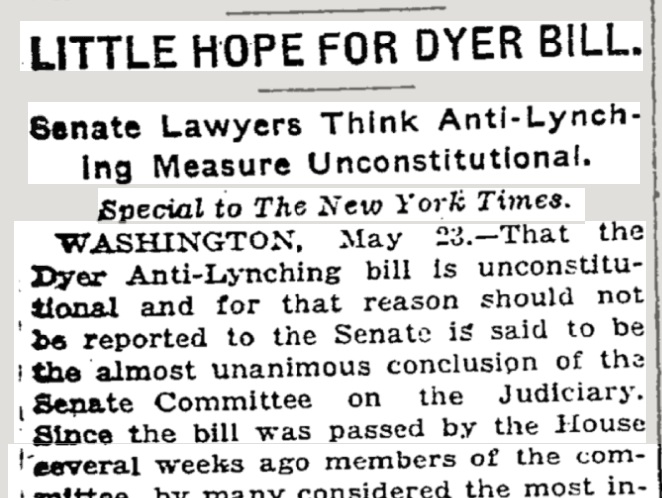

May 23, 1922: the Senate Committee on the Judiciary concluded that the Dyer Anti-Lynching bill was unconstitutional and for that reason should not be reported to the Senate.

Silent March

June 14, 1922: Blacks from Washington, DC staged a silent parade to protest continued lynchings and in an effort to promote action by Congress on the Dyer anti-lynching bill before the Senate Judiciary Committee.

June 23, 1922: at its thirteen annual conference in Newark, the NAACCP pledged the Association membership to “punish” those who oppose the Dyer bill. “The Republican Party has always received the bulk of the negro vote; the Republican Party is in power; the Republican Party has promised by its platform and its President to pass the Dyer bill. Unless the pledge is kept we solemnly pledge ourselves to use every avenue of influence to punish the persons who defeat it. We will regard no man as our friend who opposes this bill.”

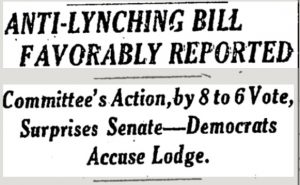

June 30, 1922: the Senate Judiciary Committee, to the surprise of the Senate, voted 8 to 6 to favorably report the Dyer Anti-Lynching bill, which would permit the Federal Government to assume prosecution of lynchings when States fall or neglect to prosecute. It was fully understood that the Senate would allow this bill to die because it stirred up so much feeling during its progress in the House.

August 14, 1922: a delegation of Black women met with President Harding to urge final Congressional action on the Dyer Anti-Lynching bill. He expressed doubt about the bill’s passage.

Dyer Anti-Lynching bill

National Equal Rights League

September 24, 1922: the National Equal Rights League sent a telegram to President Harding calling for a special session of Congress to act on the Dyer Anti-Lynching bill. Congress had adjourned without completing consideration of the bill.

November 4, 1922: the National Equal Rights League presented a petition signed by thousands of people from fifteen States calling for Congress to consider the Dyer Anti-Lynching bill.

Dyer Anti-Lynching bill

Democrat filibuster

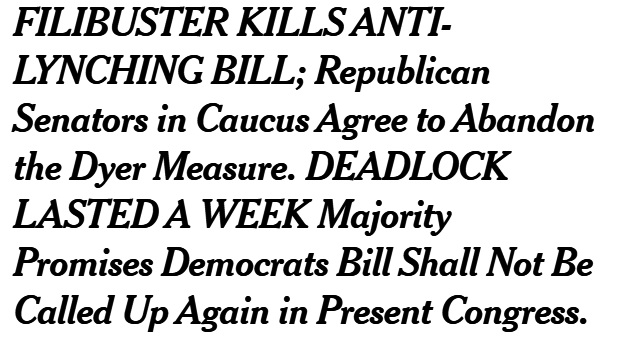

November 28, 1922: a Democrat filibuster completely deadlocked the US Senate as a result of the Republican attempt to have the Dyer Anti-Lynching bill made the unfinished business of the Senate. Senator Oscar Underwood, the Democratic leader, stated that the minority world filibuster to the end of the session if necessary, adding that so long as the majority persisted in trying to bring the bill before the Senate the opponents of the bill would refuse to permit the consideration of any other legislation.

Dyer Anti-Lynching bill

Bill lynched

December 2, 1922: the Republican caucus voted to drop the Dyer Anti-Lynching bill. Republican Senator Henry Cabot Lodge of Massachusetts stated, “The conference was in session nearly three hours and discussed the question very thoroughly. Of course the Republicans feel very strongly, as I do, that the bill ought to become a law. The situation before us was this: Under the rules of the Senate the Democrats, who are filibustering, could keep up that filibuster indefinitely, and there is no doubt they can do so.

An attempt to change the rules wold only shift the filibuster to another subject. We cannot pass the bill in this Congress and, therefore, we had to choose between giving up the whole session to a protracted filibuster or going ahead with regular business of the session….The conference decided very reluctantly that it was our duty to set aside the Dyer bill and go on with the business of the session.”

Dyer Anti-Lynching bill

Lynchings continue

July 13 1923: Dyer stated that he was not surprised at the acquittal of a George Barkwell at Columbia, Missouri on the charge of murder in connection with the lynching of James Scott, a Black. Dyer referred to statistics which, he said, showed that 3,824 lynchings had been recorded during the last thirty-five years and that in all those cases there had scarcely been a conviction.

August 24, 1923: a 34-year-old black farmhand Ben Hart was killed based on suspicion that he was a “Peeping Tom” who had that morning peered into a young white girl’s bedroom window near Jacksonville, Florida. According to witnesses, approximately ten unmasked men came to Hart’s home around 9:30 p.m. claiming to be deputy sheriffs and informing Hart he was accused of looking into the girl’s window. Hart professed his innocence and readily agreed to go to the county jail with the men, but did not live to complete the journey.

Shortly after midnight the next day, Hart’s handcuffed and bullet-riddled body was found in a ditch about three miles from the city. Hart had been shot six times and witnesses reported seeing him earlier that night fleeing several white men on foot who were shooting at him as several more automobiles filled with white men followed.

Police investigating Hart’s murder soon determined he was innocent of the accusation against him; he was at his home 12 miles away when the alleged peeping incident occurred.

October 6, 1923: a delegation from the National Equal Rights League asked President Coolidge to recommend to Congress the enactment of the Dyer bill.

The President declared his unalterable stand in behalf of the full rights of all citizens.

Dyer Anti-Lynching bill

Legacy

Other legislators proposed anti-lynching bills, but the powerful southern Democratic coalition in the Senate continued to bloc each bill.

Efforts to pass similar legislation were not taken up again until the 1930s with the Costigan-Wagner Bill. The Dyer Bill influenced the text of anti-lynching legislation promoted by the NAACP into the 1950s, including the Costigan-Wagner Bill.

On June 13, 2005, in a resolution the US Senate formally apologized for its failure to enact this and other anti-lynching bills “when action was most needed.

The resolution was the first time that members of Congress, who had apologized to Japanese-Americans for their internment in World War II and to Hawaiians for the overthrow of their kingdom, had apologized to African-Americans for any reason.

Here is a link to the full text of the 1922 Anti Lynching Bill.