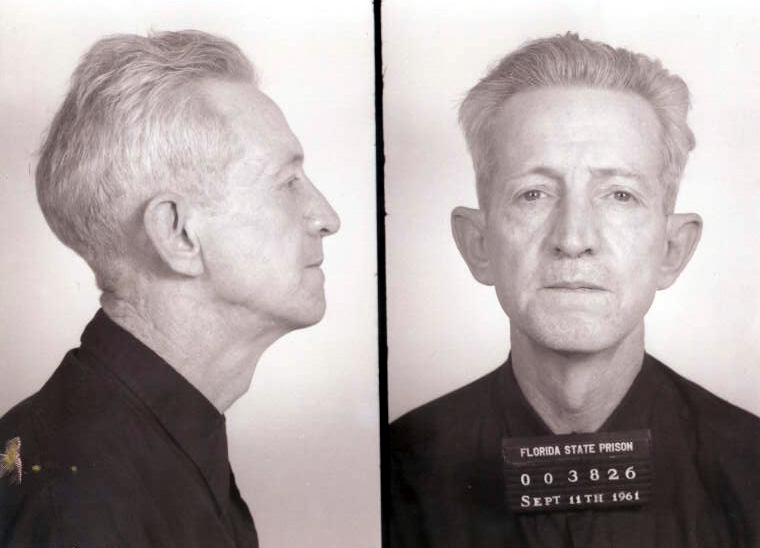

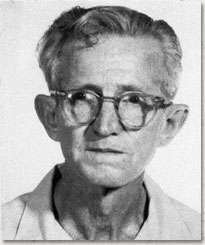

Clarence Earl Gideon

Difficult start

Clarence Earl Gideon was born in Hannibal, Missouri on August 30, 1910. His father died when Clarence was three. His mother remarried, but Clarence and his step father did not get along.

When he was 14, Clarence ran away for a year.

Back in Missouri, but not with his mother, he stole clothes, got caught, and his mother asked to have him put into a reformatory.

He was released after a year and had the scars to prove the mistreatment he received there.

Clarence Earl Gideon

Continued hard times

Gideon married and got a job in a shoe factory. He lost his job and after committing a number of crimes in Missouri was sentenced to ten years for robbery.

He was paroled but continued to run afoul the law. According to an article in the National Association of Criminal Defense Lawyers, “In 1934, he was convicted of theft of U.S. government property and conspiracy and sentenced to three years in Fort Leavenworth, where he was assigned to the shoe factory. In 1939, he was arrested on an unknown charge and again escaped from jail before trial. In 1940, he was convicted of burglary and larceny and sentenced as a repeat offender. In 1943, he escaped from prison and went to work on the Southern Pacific Railroad as a brakeman, using an assumed name and forged Selective Service card. The following year he was arrested on a tip, convicted of escape, and imprisoned until January 1950. In 1951, he was convicted of an unspecified crime in Texas and served 13 months.”

Clarence Earl Gideon

Bay Harbor Pool Room

Gideon moved to Florida. On June 3, 1961, $5 in change and a few bottles of beer and soda were stolen from Bay Harbor Pool Room (Panama, FL), a pool hall that belonged to Ira Strickland, Jr.

Henry Cook, a 22-year-old resident who lived nearby, told the police that he had seen Clarence Earl Gideon walk out of the hall with a bottle of wine and his pockets filled with coins and then get into a cab and leave. Gideon was arrested in a tavern.

August 4, 1961: being too poor to pay for counsel, Gideon requested that the court appoint one. Because of his extensive criminal record, he was familiar with that practice.

Robert McCrary, Jr, the trial judge, denied the request stating that in Florida a defendant was entitled to a court-appointed defense only in capital offense trials.

Though Gideon was mistaken is his assumption that he was entitled to a court-appointed lawyer, McCrary was also mistaken in that he could have, had he decided, appointed a lawyer.

Defending himself, Gideon was tried and convicted of breaking and entering with intent to commit petty larceny.

Clarence Earl Gideon

Sentenced to 5 years

August 25, 1961: five days before his 51st birthday, McCrary sentenced Gideon to the maximum sentence: five years in prison.

Gideon appealed his conviction to the Florida Supreme Court. That court denied his appeal.

Clarence Earl Gideon

Supreme Court petition

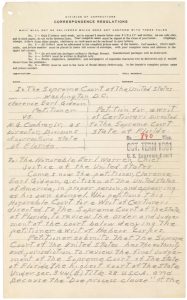

Gideon mailed a five-page hand-printed petition to the US Supreme Court asking the nine justices to consider his complaint.

It is often discussed whether, despite his familiarity with the justice system, Gideon could have written the petition himself. Some have suggested that Gideon’s cellmate, Joseph A. Peel Jr, a lawyer and judge serving time for murder, had assisted Gideon.

January 5, 1962: Whatever the circumstances, the Supreme Court, in reply, agreed to hear his appeal. Originally, the case was called Gideon v. Cochran.

January 15, 1963: the Gideon v. Cochran case was argued at the US Supreme Court. Abe Fortas was assigned to represent Gideon. Bruce Jacob, the Assistant Florida Attorney General, was assigned to argue against Gideon.

Fortas argued (a recording of Fortas’s argument can be heard via the Oyez site) that a common man with no training in law could not go up against a trained lawyer and win, and that “you cannot have a fair trial without counsel.”

Jacob argued that the issue at hand was a state issue, not federal; the practice of only appointing counsel under “special circumstances” in non-capital cases sufficed; that thousands of convictions would have to be thrown out if it were changed; and that Florida had followed for 21 years “in good faith” the 1942 Supreme Court ruling in Betts v. Brady.

The case’s original title, Gideon v. Cochran, was changed to Gideon v. Wainwright after Louie L. Wainwright replaced H. G. Cochran as the director of the Florida Division of Corrections. (NYT abstract)

Clarence Earl Gideon

Supreme court decision

March 18, 1963: the US Supreme Court unanimously ruled that, The Sixth Amendment right to counsel is a fundamental right applied to the states via the Fourteenth Amendment’s due process clause, and requires that indigent criminal defendants be provided counsel at trial. Supreme Court of Florida reversed.

In other words, the US Supreme Court unanimously ruled that those accused of a crime have a constitutional right to a lawyer whether or not they can afford one.

About 2,000 convicted people in Florida alone were freed as a result of the Gideon decision; Gideon himself was not freed. He instead got another trial. (NYT article)

Clarence Earl Gideon

Gideon’s retrial

August 5, 1963: Gideon had chosen W. Fred Turner to be his lawyer for his second trial. Turner picked apart the testimony of eyewitness Henry Cook. Turner also got a statement from the cab driver who took Gideon from Bay Harbor, Florida to a bar in Panama City, Florida, stating that Gideon was carrying neither wine, beer nor Coke when he picked him up, even though Cook had testified that he watched Gideon walk from the pool hall to the phone, then wait for a cab.

Furthermore, although in the first trial Gideon had not cross-examined the cab driver about his statement that Gideon had told him to keep the taxi ride a secret, Turner’s cross-examination revealed that Gideon had said that to the cab driver previously because “he had trouble with his wife.”

The jury acquitted Gideon after one hour of deliberation.

Clarence Earl Gideon

Attorney General Robert Kennedy

November 1, 1963: in a speech before The New England Conference on the Defense of Indigent Persons Accused of Crime, Attorney General Robert Kennedy stated: “If an obscure Florida convict named Clarence Earl Gideon had not sat down in prison with a pencil and paper to write a letter to the Supreme Court, and if the Supreme Court had not taken the trouble to look for merit in that one crude petition among all the bundles of mail it must receive every day, the vast machinery of American law would have gone on functioning undisturbed.”

Clarence Earl Gideon

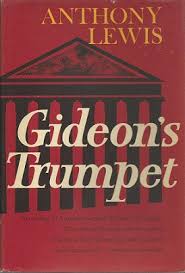

Gideon’s Trumpet

January 28, 1964,: the publication of Gideon’s Trumpet by Anthony Lewis. The book provided history of Gideon’s landmark case.

Clarence Earl Gideon

Aftermath

January 18, 1972: after his acquittal, Gideon resumed his previous way of life and married again. He died of cancer in Fort Lauderdale, Florida at age 61. Gideon’s family in Missouri accepted his body and buried him in an unmarked grave.

April 30, 1980: made for TV movie and a Hallmark Hall of Fame presentation, Gideon’s Trumpet, aired on CBS. The moved starred Henry Fonda as Clarence Earl Gideon, José Ferrer as Abe Fortas and John Houseman as Earl Warren (though Warren’s name was never mentioned in the film; he was billed simply as “The Chief Justice”). Houseman also provided the off screen closing narration at the end of the film. Lewis himself appeared in a small role as “The Reporter”.

November 1984 The local chapter of the American Civil Liberties Union added a granite headstone, inscribed with a quote from a letter Gideon wrote to his attorney, Abe Fortas: “I believe that each era finds an improvement in law for the benefit of mankind.”

Clarence Earl Gideon

Law v reality

March 16, 2013: approaching the 50th anniversary of Gideon v. Wainwright, a NYT article stated, the Legal Services Corporation, the Congressionally financed organization that provides lawyers to the poor in civil matters, says there are more than 60 million Americans — 35 percent more than in 2005 — who qualify for its services. But it calculates that 80 percent of the legal needs of the poor go unmet. In state after state, according to a survey of trial judges, more people are now representing themselves in court and they are failing to present necessary evidence, committing procedural errors and poorly examining witnesses, all while new lawyers remain unemployed… According to the World Justice Project, a nonprofit group promoting the rule of law that got its start through the American Bar Association, the United States ranks 66th out of 98 countries in access to and affordability of civil legal services.