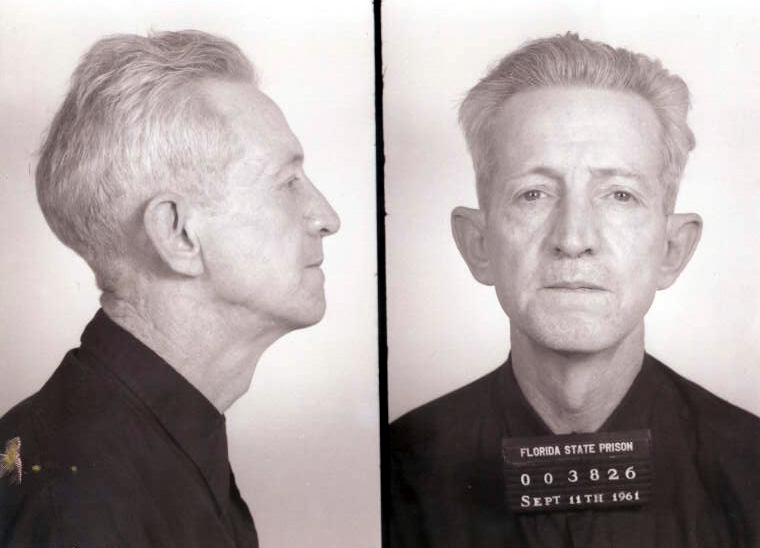

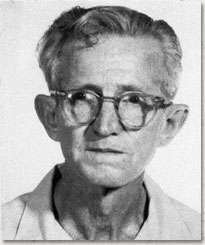

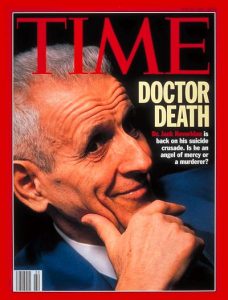

Doctor Jacob Jack Kevorkian

For most people, death is an uncomfortable topic, particularly one’s own mortality. We speak of people “passing,,” not dying. We choose healthy lifestyle, hoping to postpone the inevitable.

For most people, death is an uncomfortable topic, particularly one’s own mortality. We speak of people “passing,,” not dying. We choose healthy lifestyle, hoping to postpone the inevitable.

Others challenge the actuarial tables by smoking, drinking excessively, eating as much and whatever whenever, driving without seat belts, or something else society warns us not to do.

Doctor Jacob Jack Kevorkian

Only the good die young?

Regardless of our personal life style, regardless of others’ life styles, death comes. to the young, the old, those between, those healthy, and those ill. To all.

Many dream of a quiet death surrounded by loved ones who had the time to get to their bedside in a comfortable setting and with had the time to impart sage advice. Forgiveness.

For others, death comes as a horrifically slow and painful chronic illness.

Jack Kevorkian hoped to provide solace to the latter.

Doctor Jacob Jack Kevorkian

Early life

Kevorkian was born in Pontiac, Michigan, on May 26, 1928.In 1952, he graduated from the University of Michigan Medical School. His parents had survived the Armenian holocaust in Turkey.

As a young doctor, some of his views were medically and socially non-traditional. For example, he proposed that society give death row prisoners the choice to undergo capital punishment by medical experimentation while under anesthesia.

The medical community denied any such procedure.

Kevorkian proposed, based on successful research, the transfusion of blood from dead patients to patients in need of blood. He proposed the idea to the military.

The military denied such a procedure.

Doctor Jacob Jack Kevorkian

Euthanasia

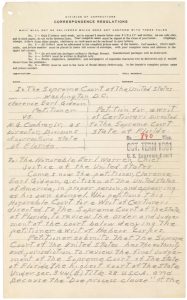

It is no surprise, then, that euthanasia became on of Kevorkian’s interests and on June 4, 1990 he was present at the death of Janet Adkins, a 54-year-old Portland, Oregon, woman with Alzheimer’s disease.

It is no surprise, then, that euthanasia became on of Kevorkian’s interests and on June 4, 1990 he was present at the death of Janet Adkins, a 54-year-old Portland, Oregon, woman with Alzheimer’s disease.

Her death occurred in Kevorkian’s 1968 Volkswagen van in Groveland Oaks Park near Holly, Michigan.

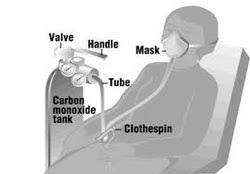

He used a device he developed called that “Thanatron” from the Greek works for death and machine. It worked by the patient pushing a button to deliver the euthanizing drugs mechanically through an IV. It had three canisters mounted on a metal frame. Each bottle had a syringe that connected to a single IV line in the person’s arm. One contained saline, another contained a sleep-inducing barbiturate called sodium thiopental and the third a lethal mixture of potassium chloride, which immediately stopped the heart, and pancuronium bromide, a paralytic medication to prevent spasms during the dying process.

On June 5 he gave an interview to the NY Times about Adkins. In it he prophetically said that, “”They’ll all be after me for this. My ultimate aim is to make euthanasia a positive experience. I’m trying to knock the medical profession into accepting its responsibilities, and those responsibilities include assisting their patients with death.”

Doctor Jacob Jack Kevorkian

Legal issues begin

June 8, 1990: an Oakland County Circuit Court Judge enjoined Kevorkian from aiding in any suicides.

December 12, 1990: District Court Judge Gerald McNally dismissed the murder charge against Kevorkian in death of Adkins.

Doctor Jacob Jack Kevorkian

1991

February 5, 1991: a Michigan court barred Kevorkian from assisting in suicides.

October 23, 1991: Kevokian attended the deaths of Marjorie Wantz, a 58-year-old Sodus, Michigan, woman with pelvic pain, and Sherry Miller, a 43-year-old Roseville, Michigan, woman with multiple sclerosis. The deaths occur at a rented state park cabin near Lake Orion, Michigan. Wantz died from the suicide machine’s lethal drugs, Miller from carbon monoxide poisoning inhaled through a face mask.

Kevorkian would stop using the Thantran and began to use what he called the Mercitron (“mercy machine”). The Mercitron used a mask through which a person inhaled carbon dioxide.

Kevorkian would stop using the Thantran and began to use what he called the Mercitron (“mercy machine”). The Mercitron used a mask through which a person inhaled carbon dioxide.

November 20, 1991: the Michigan state Board of Medicine summarily revoked Kevorkian’s license to practice medicine in Michigan.

Doctor Jacob Jack Kevorkian

1992

May 15, 1992: Susan Williams, a 52-year-old woman with multiple sclerosis, died from carbon monoxide poisoning in her home in Clawson, Michigan.

July 21, 1992: Oakland County Circuit Court Judge David Breck dismissed charges against Kevorkian in the deaths of Miller and Wantz.

September 26, 1992: Lois Hawes, 52, a Warren, Michigan, woman with lung and brain cancer, dies from carbon monoxide poisoning at the home of Kevorkian’s assistant Neal Nicol in Waterford Township, Michigan.

November 23, 1992: Catherine Andreyev of Moon Township, Pennsylvania, died in Kevorkian’s assistant Neil Nicol’s home. She was 45 and had cancer. Hers is the first of 10 deaths Kevorkian attended over the next three months; all die from inhaling carbon monoxide.

December 3, 1992: The Michigan Legislature passed a ban on assisted suicide to take effect on March 30, 1993.

Doctor Jacob Jack Kevorkian

1993

February 15, 1993: Hugh Gale, a 70-year-old man with emphysema and congestive heart disease, died in his Roseville home. Prosecutors investigated after Right-to-Life advocates said that they found papers that showed Kevorkian altered his account of Gale’s death, deleting a reference to a request by Gale to halt the procedure.

The investigator’s follow up investigation read: “It is my decision that no charges will be filed against Dr. Jack Kevorkian or any other person in connection with the death of Hugh Gale. Mr. Gale’s death can only be regarded as a suicide. Those present at the time of his death did nothing more than provide the means for him to accomplish a result that he desired. The great weight of evidence is that he never faltered in that desire up to the point that he lost consciousness.”

February 25, 1993: Michigan Governor John Engler signs the legislation banning assisted suicide. It makes aiding in a suicide a four-year felony but allows law to expire after a blue-ribbon commission studies permanent legislation.

April 27, 1993: a California law judge suspended Kevokian’s medical license after a request from that state’s medical board.

August 4, 1993: Thomas Hyde, a 30-year-old Novi, Michigan, man with ALS, is found dead in Kevorkian’s van on Belle Isle, a Detroit park.

September 9, 1993: hours after a judge ordered him to stand trial in Thomas Hyde’s death, Kevorkian is present at the death of cancer patient Donald O’Keefe, 73, in Redford Township, Michigan.

November 5 – 8, 1993: Kevorkian fasts in Detroit jail after refusing to post $20,000 bond in case involving Hyde’s death.

November 29, 1993: Kevorkian begins fast in Oakland County jail for refusing to post $50,000 bond after being charged in the October death of Merian Frederick, 72.

December 17, 1993: he ended fast and left jail after Oakland County Circuit Court Judge reduced bond to $100 in exchange for his vow not to assist in any more suicides until state courts resolved the legality of his practice.

Doctor Jacob Jack Kevorkian

1994

January 27, 1994: a Circuit Court Judge dismissed charges against Kevorkian in two deaths, becoming the fifth lower court judge in Michigan to rule that assisted suicide was a constitutional right.

May 2, 1994: a Detroit jury acquitted Kevorkian of charges he violated the state’s assisted suicide ban in the death of Thomas Hyde.

May 10, 1994: The Michigan Court of Appeals strikes down the state’s ban on assisted suicide on the grounds it was enacted unlawfully.

November 8, 1994: Oregon became the first state to legalize assisted suicide when voters passed a tightly restricted Death with Dignity Act. Legal appeals kept the law from taking effect until 1997.

November 26, 1994: hours after Michigan’s ban on assisted suicide expired, 72-year-old Margaret Garrish died of carbon monoxide poisoning in her home in Royal Oak. She had arthritis and osteoporosis. Kevorkian was not present when police arrived.

December 13, 1994: the Michigan Supreme Court upheld the constitutionality of Michigan’s 1993-94 ban on assisted suicide and also rules assisted suicide is illegal in Michigan under common law. The ruling reinstated cases against Kevorkian in four deaths

Doctor Jacob Jack Kevorkian

1995

June 26, 1995: Kevorkian opened a “suicide clinic” in an office in Springfield Township, Michigan. Erika Garcellano, a 60-year-old Kansas City, Missouri, woman with ALS, is the first client. A few days later, the building’s owner kicks out Kevorkian.

September 14, 1995: Kevorkian arrived at the Oakland County Courthouse in Pontiac, Michigan in homemade stocks with ball and chain. He is ordered to stand trial for assisting in the 1991 suicides of Sherry Miller and Marjorie Wantz.

October 30, 1995: a group of doctors and other medical experts in Michigan announced its support of Kevorkian , saying they will draw up a set of guiding principles for the “merciful, dignified, medically-assisted termination of life.”

Doctor Jacob Jack Kevorkian

1996

February 1, 1996: the New England Journal of Medicine published massive studies of physicians’ attitudes towards doctor-assisted suicide in Oregon and Michigan. The studies demonstrated that a large number of physicians surveyed support, in some conditions, doctor-assisted suicide. [2000 NEJM article]

March 6, 1996, : the 9th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals in San Francisco ruled that mentally competent, terminally ill adults have a constitutional right to aid in dying from doctors, health care workers and family members. It is the first time a federal appeals court endorses assisted suicide.

March 8, 1996, a jury acquitted Kevorkian in two deaths.

March 20, 1996: Rep Dave Camp (R-MI), introduced a bill in the US House of Representatives to prohibit tax-payer funding of assisted suicide.

April 1, 1996, trial began in Kevorkian’s home town of Pontiac in the deaths of Miller and Wantz. For the start of his third criminal trial, he wears colonial costume–tights, a white powdered wig, and big buckle shoes–a protest against the fact that he is being tried under centuries-old common law. He would face a maximum of five years in prison and a $10,000 fine if convicted in the Wantz/Miller deaths.

May 14, 1996: jury acquitted Kevorkian.

November 4, 1996: Kevorkian’s lawyer announced a previously unreported assisted suicide of a 54-year-old woman. This brought the total number of his assisted suicides, since 1990, to 46.

Doctor Jacob Jack Kevorkian

1997

June 12, 1997, in Kevorkian’s fourth trial, a judge declared a mistrial. The prosecution later dropped the case.

June 26, 1997: in Washington v. Glucksberg. The U.S. Supreme Court rules unanimously that state governments have the right to outlaw doctor-assisted suicide. The Court had been asked to decide whether state laws banning the practice in New York and Washington were unconstitutional. (Oyez article)

October 27, 1997: the Oregon Death with Dignity Act, which voters had approved by referendum on November 8, 1994, and which allowed voluntary end of life, took effect on this day. The law allowed individuals to voluntarily end their own lives by ingesting a life-ending drug that a licensed physician prescribed.

The law has survived two challenges. Oregon voters rejected a repeal measure by a margin of 60 percent in 1997. And in 2006, the Supreme Court upheld the law, in Gonzales v. Oregon. (Oregon Health Authority article)

Doctor Jacob Jack Kevorkian

1998

March 14, 1998: Kevorkian’s 100th assisted suicide, a 66-year-old Detroit man.

September 1, 1998: Michigan’s second law outlawing physician-assisted suicide goes into effect.

September 17, 1998: Kevorkian videotapesd the voluntary euthanasia of Thomas Youk, 52, who was in the final stages of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. He sent the tape to CBS.

November 3, 1998: Michigan voters rejected a proposal to legalize physician-assisted suicide for the terminally ill.

November 22, 1998: CBS’s “60 Minutes” aired Kevorkian’s videotape of Thomas Youk. The broadcast triggered an intense debate within medical, legal and media circles. [60 Minutes Overtime article]

November 25, 1998: Michigan charged Kevorkian with first-degree murder, violating the assisted suicide law and delivering a controlled substance without a license in the death of Thomas Youk. Prosecutors later drop the suicide charge. Kevorkian insists on defending himself during the trial and threatens to starve himself if he is sent to jail.

Doctor Jacob Jack Kevorkian

1999

March 26, 1999: Kevorkian convicted of second-degree murder for giving a lethal injection to an ailing man whose death was shown on “60 Minutes.”

April 13, 1999: Michigan judge Jessica Cooper of Oakland County Circuit Court sentenced Kevorkian to 10 – 25 years in prison for conviction of second-degree murder and delivery of a controlled substance in the death of Thomas Youk. [CNN article]

Cooper denied bail pending appeal and said to Kevorkian that, “This trial was not about the political or moral correctness of euthanasia…It was about you, sir. It was about lawlessness.”

Doctor Jacob Jack Kevorkian

21st Century

September 29, 2005: in an MSNBC interview, by Rita Cosby Kevorkian said that if he were granted parole, he would not resume directly helping people die and would restrict himself to campaigning to have the law changed.

When asked if he had any regrets, he responded: “Well, I do a little. It was disappointing because what I did turned out to be in vain, even though I know it could possibly end that way. And my only regret was not having done it through the legal system, through legislation, possibly.”

December 22, 2005: Kevorkian was again denied parole by a board.

Doctor Jacob Jack Kevorkian

Paroled

June 1, 2007: paroled for good behavior. He had spent eight years and two and a half months in prison. On June 4, the NY Times published an interview with him following his release.

In it he said that, ““I said I won’t do it again,” he said, “and it’s not even worth doing again by me because it’d be counterproductive to what I’m fighting for. It’s up to others. If you people don’t want that right, then don’t do it. Then let your government trample all over you. If you don’t want to do it, it’s all right by me, but you don’t get me talking about it and going back to that thing called prison.”

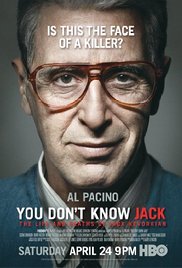

April 14 , 2010: the HBO film You Don’t Know Jack premiered at the Ziegfeld Theater in New York City. Kevorkian walked the red carpet alongside Al Pacino, who portrayed him in the film. Pacino received Emmy and Golden Globe awards for his portrayal, and personally thanked Kevorkian, who was in the audience, upon receiving both of these awards. Kevorkian stated that both the film and Pacino’s performance “brings tears to my eyes – and I lived through it.”

April 14 , 2010: the HBO film You Don’t Know Jack premiered at the Ziegfeld Theater in New York City. Kevorkian walked the red carpet alongside Al Pacino, who portrayed him in the film. Pacino received Emmy and Golden Globe awards for his portrayal, and personally thanked Kevorkian, who was in the audience, upon receiving both of these awards. Kevorkian stated that both the film and Pacino’s performance “brings tears to my eyes – and I lived through it.”

New York Times reviewer Alessandra Stanley wrote, “When it comes to assisted suicide, it is possible to love the sin and hate the sinner.”

Doctor Jacob Jack Kevorkian

Death

June 3, 2011: Kevorkian died after being hospitalized with kidney problems and pneumonia eight days earlier. (NYT obit)

Many of the dates from this chronology come from PBS dot org Frontline