Sunrise to Sunset Festival

May 31 – June 2, 1969

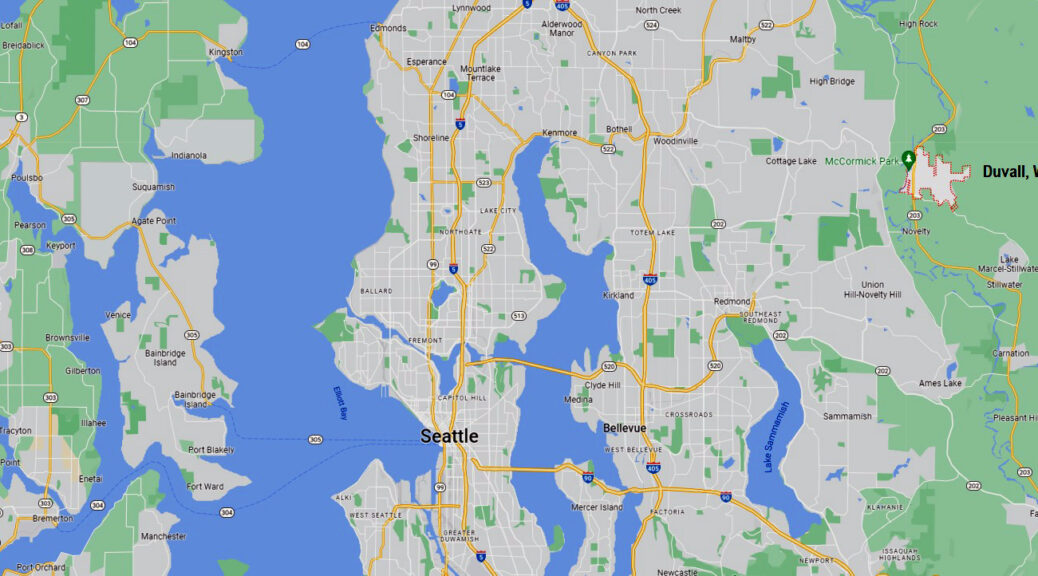

Stanley Carlson farm in Duvall, WA

(after the Tulalip Indian Reservation in Marysville, WA cancelled)

1969 festival #10

Duvall is a city in King County, Washington, located on SR 203 halfway between Monroe and Carnation. The population was 8,034 at the 2020 census.

As a myopic Woodstock 1969 alum, I always thought that Woodstock was the only 1969 festival other than in the infamous Altamont at the end of the year.

I’ve learned repeatedly how wrong I was and am continually astounded at how many other 1969 festivals there were: at least 49, most of which were in the United States.

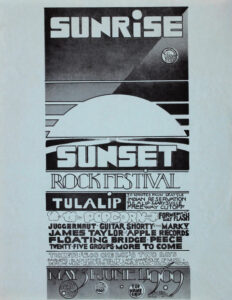

In October 2022, Glen Beebee, a reader posted a comment under my post about those other festivals. He pointed out that I had missed (yet) another one: the Sunrise to Sunset Festival in Duvall, Washington. He provided the jpegs of the concert poster as well as the newspaper article. Thank you Glen.

Otherwise, I find very little about it. I did find a reference to two nearby 1968 events: a piano drop and a festival. Here’s a bit about them.

BTW…Glen also points out that there was also the Spring Flush (Santana, It’s a Beautiful Day, Peanut Butter Conspiracy, Spring,Alice Stuart (Thomas), Gazebo, Juggernaut, Retina Circus (light show) at HEC Edmundson Pavilion 5/3/69. Very subjectively, I’ve limited my accounting of 1969 festivals to multi-day events, so will not include the Spring Flush on my list, but it does point out two things: one, there was a lot of outdoor rock music happening by 1969 and two, the Northwest played (literally and figuratively) a big part in that cornucopia.

Sunrise to Sunset Festival

Great Piano Drop, 1968

Duvall had already experienced another counter-cultural event. On April 28, 1968 there was the Great Piano Drop on musician Larry Vanover’s farm in Duvall. A helicopter dropped an upright piano into a field just so everyone could hear what it would sound like. Organizers thought if they could get people out to a rural spot to watch a piano drop, then they’d come out to a festival, too.

If you are a Northern Exposure fan, a piano drop will sound familiar as in the February 3, 1992 episode Burning Down the House, Chris initially decided to fling a cow, but did a piano instead.

And (of course) that plot was likely inspired by Monty Python who occasionally used the idea in episodes. A video game also uses the concept:

Sunrise to Sunset Festival

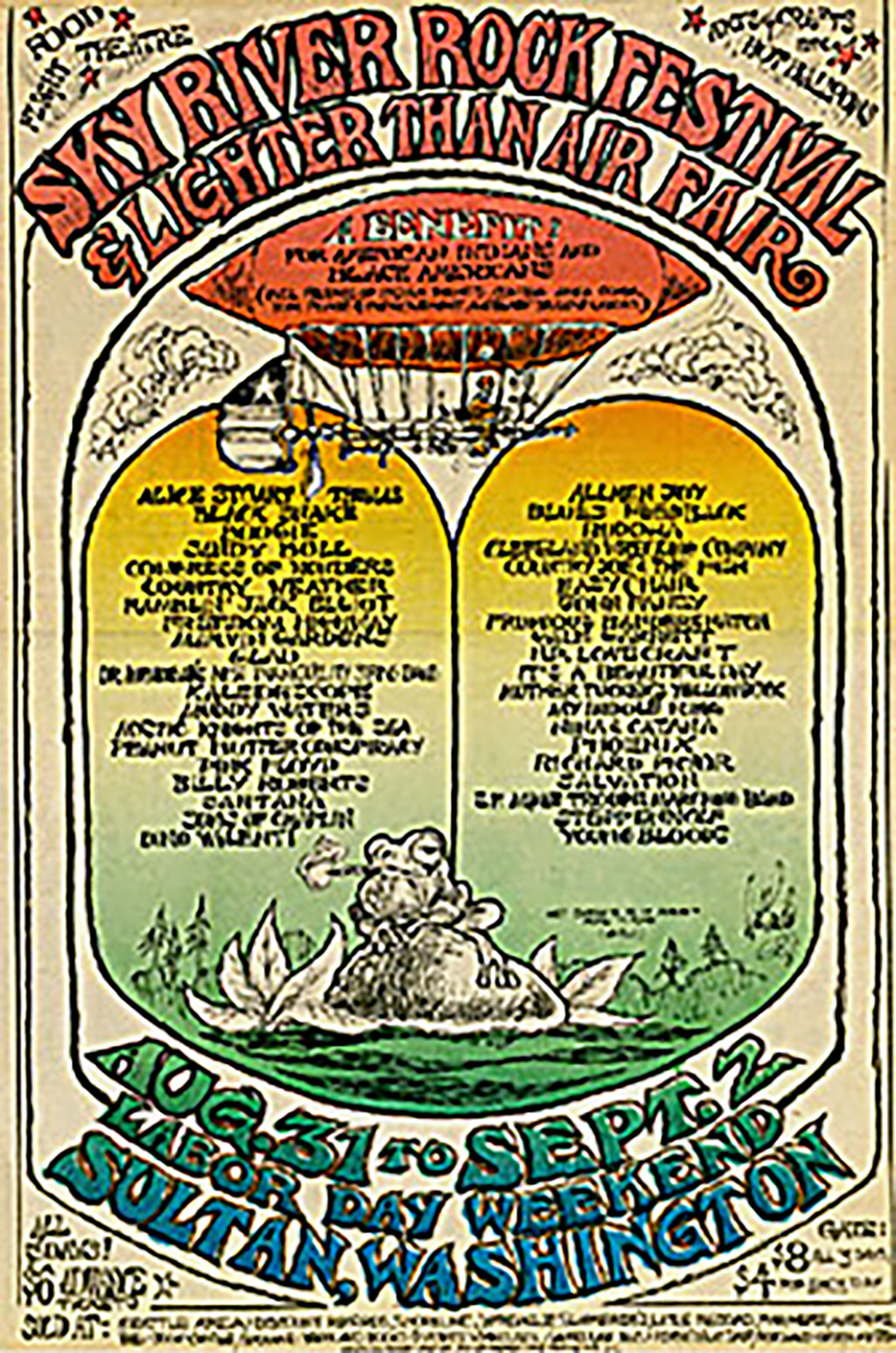

Sky River Festival, 1968

Over Labor Day weekend that year, the Great Piano Drop yielded its fruit: the Sky River Festival. It was likely America’s first outdoor, multi-day hippie rock festival on an undeveloped site. Think Woodstock, but a year earlier.

From an April 23, 2015 article by Ben Marks in Collectors Weekly:

…the organizers of Woodstock may well have taken their cue from the Sky River Rock Festival and Lighter Than Air Fair, held over Labor Day weekend of 1968,… At Sky (short for Skykomish) River, some 20,000 people descended on Betty Nelson’s organic raspberry farm in Sultan, Washington, to turn on, frolic naked in the mud, and tune into the music of 20 or so bands and performers, playing everything from folk and blues to jazz and rock. A young Richard Pryor was there (his debut comedy album would be released that November), as was the Grateful Dead, whose unscheduled appearance on the last day of the festival was as big a surprise to the concert’s exhausted and bewildered promoters as it was to the appreciative crowd.

But I digress. “What about the Sunrise to Sunset Festival,” you ask. I digress for a good reason: I can find very little about the festival other than it did actually happen. The above referenced AP article is The Daily Chronicle from Monday 2 June 1969. The headline reads: Hippies Take To the Hills.

The articles first sentence reads …hippies and some of the not-so-hip took to the hills during the Memorial Day weekend to follow the Sunrise to Sunset Rock Festival as it moved from Marysville to this tiny King County community, scene of a piano drop last April.

Sunrise to Sunset Festival

30 Bands

The article says that there were 30 bands, but does not mention one of them. Apparently the biggest local issue was a traffic jam when a parking area flooded, The wunderground.com site shows it was somewhat a chilly weekend that had had rain some rain in the days before.

Sunrise to Sunset Festival

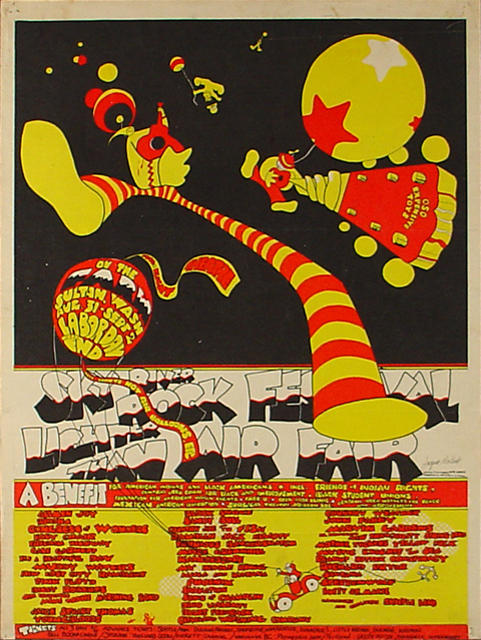

Sky River Rock Festival & Lighter Than Air Fair, 1969

Tenino, Washington is nearly 100 miles south of Duvall and on August 30, 31, and September 1, 1969 was the Sky River Rock Festival and Light Than Air Fair. Besides have what is likely the longest name of any fair that year (or ever?).

Follow my link above to read all about it.

Or follow this link to 1969’s festival #11: The Mississippi River Festival.

Sunrise to Sunset Festival

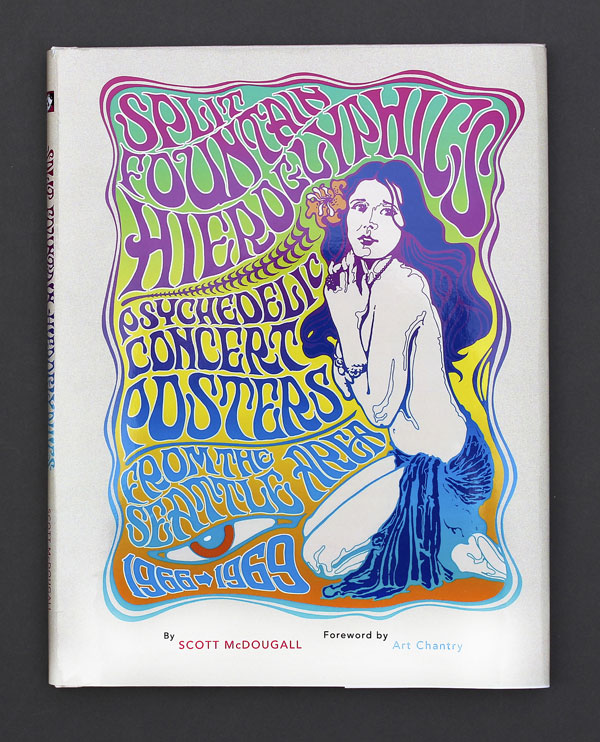

SPLIT FOUNTAIN HIEROGLYPHICS

And a shout out to Glen and his associates for their book: Split Fountain Hieroglyphics: Psychedelic Concert Posters from the Seattle Area, 1966-1969.

From their site: The 60’s Seattle area poster scene has been chronicled in this new, hardcover, 150 page volume titled: Split Fountain Hieroglyphics: Psychedelic Concert Posters from the Seattle Area, 1966-1969. With help from Glen Beebe (design/production), Ben Marks (editor) and a foreword by Art Chantry, I’ve published a limited edition of 500, signed and numbered books. With almost 200, full color illustrations of concert art, artist interviews and essays covering topics such as the Piano Drop and Sky River,

Sunrise to Sunset Festival

Next 1969 festival: Mississippi River Festival