American Slave Revolts

Growing up it was easy to believe the lie that the American slaves didn’t mind being slaves. Their owners took care of them; provided a place for them to live; provided food and clothing.

The American Negro, we were told, weren’t a capable as whites anyway, so the caring for slaves was as much an act of mercy as it was an economic benefit.

Such fake news.

American Slave Revolts

Kidnapped/enslaved

August 19, 1619: the first enslaved Africans arrived in the Virginia colony at Point Comfort on the James River. There, “20 and odd Negroes” from the White Lion, an English ship, were sold in exchange for food; the remaining Africans were transported to Jamestown and sold into slavery.

Historians have long believed that these first African slaves in the colonies came from the Caribbean but Spanish records suggest they were captured in the Portuguese colony of Angola, in West Central Africa.

While aboard the ship São João Bautista bound for Mexico, they were stolen by two English ships, the White Lion and the Treasurer. Once in Virginia, the enslaved Africans were dispersed throughout the colony.

American Slave Revolts

Revolts begin

That any human would want to be held against their will as long as their “owner” chose is incomprehensible after a moment’s thought, but the belief persisted. And any attempted insurrection was violently put down and then denied. The victors wrote the history and they left out revolts.

But revolts there were…

Servents’ Plot

September 13, 1663: first serious slave conspiracy in colonial America. White servants and black slaves conspired to revolt in Gloucester County, VA, but were betrayed by a fellow servant.

Virginia legalizes murder

October 20, 1669: the Virginia Colonial Assembly enacted a law that removed criminal penalties for enslavers who killed enslaved people resisting authority. The assembly justified the law on the grounds that “the obstinacy of many [enslaved people] cannot be suppressed by other than violent means.” The law provided that an enslaver’s killing of an enslaved person could not constitute murder because the “premeditated malice” element of murder could not be formed against one’s own property. [EJI article]

American Slave Revolts

Early 1700s

Newton, Long Island

February 28, 1708: seven white people were killed in Newton, Long Island. Following the rebellion, two black male slaves and an Indian slave were hanged, and a black woman was burned alive.

Virginia

In 1709: a plot involving enslaved Indians as well as Africans spread through at least three Virginia counties—James City, Surry, and Isle of Wight. Of the four ringleaders, Scipio, Salvadore, Tom Shaw, and Peter, all but Peter were quickly jailed.

Virginia a year later

April 20 (Easter), 1710: another Virginia conspiracy in the same area as 1709—perhaps inspired by Peter and involving only African American slaves—was to have begun on Easter 1710.

A slave named Will, however, betrayed it to authorities. Will got his freedom and his owner Robert Ruffin was reimbursed for his value with £40 of public money.

Two of the plot’s leaders were tried by the General Court, convicted, and executed. Wrote Governor Edmund Jenings in his report to the London Lords of Trade, “I hope their fate will strike such terror in the other negroes as will keep them from forming such designs for the future, without being obliged to make an example of any more of them.”

American Slave Revolts

17-teens

New York City

April 6, 1712: New York City had a large enslaved population and the city’s whites feared the threat of rebellion. Enslaved people in New York City suffered many of the same brutal punishments and methods of control faced by their counterparts toiling on Southern plantations. The labor demands of urban life required enslaved people to move frequently throughout the city to complete tasks. This brought greater freedom of movement and communication for the enslaved, which they used to organize a rebellion against their harsh living conditions and lack of autonomy.

Organizers from several ethnic groups, including the Akans of West Africa, who viewed the colonial master-servant relationship as a violation of Akan tradition; the Caromantees and Paw-Paws, also of West Africa, who rejected the brutality of slavery; Spanish-speaking Native Americans who viewed themselves as free people who had been illegally enslaved; and Creoles, who joined in protest of their status and harsh treatment, came together to plan a revolt.

The coalition set fire to a building in the center of the city. Armed with hatchets, knives, and guns, the rebels attacked whites as they arrived at the fire, killing nine and injuring seven. Colonial Governor Robert Hunter dispatched troops to quell the rebellion. The troops arrested some rebels and captured others who fled into the woods. Six of the revolt’s organizers reportedly committed suicide, twenty-one accused rebels were convicted and executed, and thirteen were acquitted and returned to bondage.

American Slave Revolts

1720s

Governor Hugh Drysdale, VA

In 1722: When Hugh Drysdale arrived in Williamsburg in 1722 to begin his term as Virginia’s governor, he found the jail full of mutinous slaves awaiting trial. Three of the leaders were convicted of “Conspiring among themselves and with the said other Slaves to kill murder & destroy very many” of His Majesty’s subjects and sentenced to be sold out of the colony. According to Drysdale, their design “…was to cutt off their masters, and possess themselves of the country; but as this would have been as impracticable in the attempt as it was foolish in the contrivance, I can foresee no other consequence of this conspiracy than the stirring upp the next Assembly to make more severe laws for keeping their slaves in greater subjection etc.”

Every slave rebellion or rumor of plotting resulted in laws increasing the severity of punishment, curtailing slaves’ movements, and restricting their ability to assemble, attend funerals or religious services, or possess weapons.

American Slave Revolts

1730s

Governor William Gooch, VA

1730: Virginia’s Governor William Gooch reported to the Board of Trade that another slave uprising had been scotched. The spark was a false rumor that “His Majesty had sent Orders for setting of them free as soon as they were Christians, and that these Orders were Suppressed.” Gooch tried to learn the source of this falsehood and called out the militia to take up any slave found off his master’s plantation. “A great many” were made prisoner and were whipped for “rambling Abroad,” and by this method Gooch hoped “to Convince them that their best way is to rest contented with their Condition.”

1730: Six months after the above revolt, another insurrection began. Governor Gooch wrote: Negros, in the Countys of Norfolk & Princess Anne, had the boldness to Assemble on a Sunday while the People were at Church, and to Chuse from amongst themselves Officers to Comand them in their intended Insurrection, which was to have been put in Execution very soon after: But this Meeting being happily discovered and many of them taken up and examined, the whole Plot was detected.

After a trial, four ringleaders were executed and the rest harshly punished.

South Carolina Security Act

Mid-August, 1739: South Carolina Security Act. The Act was a response to the white’s fears of insurrection, the act required that all white men carry firearms to church on Sundays, a time when whites usually didn’t carry weapons and slaves were allowed to work for themselves. Anyone who didn’t comply with the new law by September 29 would be subjected to a fine.

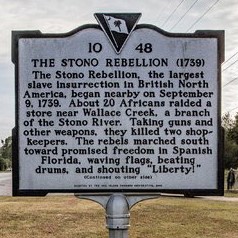

Stono Riverm, SC

September 9, 1739: early on the morning of the 9th, a Sunday, about twenty slaves gathered near the Stono River in St. Paul’s Parish, less than twenty miles from Charlestown. SC. The slaves went to a shop that sold firearms and ammunition, armed themselves, then killed the two shopkeepers who were manning the shop. From there the band walked to the house of a Mr. Godfrey, where they burned the house and killed Godfrey and his son and daughter. They headed south. It was not yet dawn when they reached Wallace’s Tavern. Because the innkeeper at the tavern was kind to his slaves, his life was spared. The white inhabitants of the next six or so houses they reach were not so lucky — all were killed. The slaves belonging to Thomas Rose successfully hid their master, but they were forced to join the rebellion. (They would later be rewarded. See Report re. Stono Rebellion Slave-Catchers.) Other slaves willingly joined the rebellion. By eleven in the morning, the group was about 50 strong. The few whites whom they now encountered were chased and killed, though one individual, Lieutenant Governor Bull, eluded the rebels and rode to spread the alarm.

The slaves stopped in a large field late that afternoon, just before reaching the Edisto River. They had marched over ten miles and killed between twenty and twenty-five whites.

Around four in the afternoon, somewhere between twenty and 100 whites had set out in armed pursuit. When they approached the rebels, the slaves fired two shots. The whites returned fire, bringing down fourteen of the slaves. By dusk, about thirty slaves were dead and at least thirty had escaped. Most were captured over the next month, then executed; the rest were captured over the following six months — all except one who remained a fugitive for three years.

American Slave Revolts

North

NYC

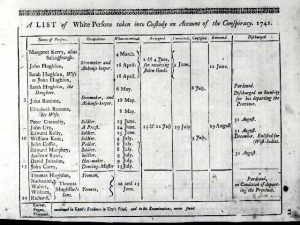

March and April 1741: series of suspicious fires and reports of slave conspiracy led to general hysteria in New York City,

Thirty-one slaves, five whites executed.

Massachusetts

January 6, 1773: Massachusetts slaves petitioned legislature for freedom. There were 8 such petitions during the Revolutionary War period.

American Slave Revolts

Toussaint Louverture

August 22, 1791: Haiti slave revolt. Former slave Toussaint Louverture led a slave revolt in Haiti, West Indies. He is captured in 1802, but the revolt continues and Haitian independence is declared.

The event terrified Southern slave owners and supporters of slavery.

American Slave Revolts

Gabriel Prosser

August 30, 1800: in the spring of 1800, Gabriel Prosser, a deeply religious man, began plotting an invasion of Richmond, Virginia and an attack on its armory.

By summer he had enlisted more than 1,000 slaves and collected an armory of weapons, organizing the first large-scale slave revolt in the U.S. On the day of the revolt, the bridges leading to Richmond are destroyed in a flood, and Prosser was betrayed.

The state militia attacked, and Prosser and 35 of his men were hanged on October 10, 1800.

October 28, 2002: the City Council in Richmond, the former capital of the Confederacy, unanimously voted to honor Gabriel Prosser. The resolution called him an ”American patriot and freedom fighter” and added that ”This resolution seeks to correct an error in history whereby Gabriel has been seen by many as a criminal,’‘ Councilman Sa’ad El-Amin told the Council.

American Slave Revolts

Nat Turner

October 2, 1800: Nat Turner born in Southampton County, Virginia, the week Gabriel Prosser was hanged. While still a young child, Nat was overheard describing events that had happened before he was born. This, along with his keen intelligence, and other signs marked him in the eyes of his people as a prophet “intended for some great purpose.” [see Turner for expanded story]

American Slave Revolts

Charles Deslondes

January 8, 1811: Charles Deslondes led a rebellion of some 500 enslaved black people in New Orleans, Louisiana, in what became known as the German Coast Uprising.

After black people in Haiti won their independence from the French in 1804 following a thirteen-year war, surviving white planters relocated from Haiti to Orleans Territory (now the State of Louisiana). Many brought with them enslaved black laborers, including Charles Deslondes, who had been born into slavery in Haiti. Orleans Territory’s black population tripled between 1803 and 1811, leaving whites fearful of a black rebellion.

In early January 1811, Charles Deslondes convened a meeting of enslaved black people to plan an anti-slavery rebellion in New Orleans. The rebellion began on January 8, 1811, with a plantation attack that left one white man dead. The rebels then traveled along the Mississippi River, attacking plantations and recruiting more fighters. Some enslaved blacks joined the rebels, while others warned their masters and tried to avert plantation attacks. Many whites escaped across the river.

January 11, 1811: a militia of white planters confronted Charles Deslondes and the rebels in a brief battle, killing many and forcing others to flee. Deslondes and his supporters were captured. Some were returned to their plantations; others were tried and executed, their corpses publicly displayed as warning against future uprisings. The final death toll included two whites and ninety-five blacks. The territorial legislature later voted to financially compensate whites whose enslaved black laborers had been killed.

George Boxley attempts revolt

March 6, 1815: George Boxley was a white storekeeper and mill owner. While living in Berkeley Parrish, Spotsylvania County, Virginia, he allegedly tried to coordinate a local slave rebellion in 1815, based on “heaven-sent” orders to free the enslaved. His plan was for slaves from Spotsylvania, and surrounding counties to meet at his home with horses, guns, swords and cubs. His plan involved capturing Richmond’s magazine or arsenal, and from there he planned to help the participating enslaved reach freedom. An enslaved girl, Lucy, informed her owner, Ptolemy Powell, who then informed the magistrate.

The plot was foiled. At least six enslaved people were executed and many others were arrested. Boxley was able to escape from the Spotsylvania County Jail when his wife, brought him a file, which he used to cut his chains and escape to freedom. A thousand dollars reward was offered for Boxley, but he was never caught. Boxley fled to Indiana, where he continued to help runaways and teach the principles of abolitionism on the railway to freedom. [NPS article]

American Slave Revolts

Fort Blount revolt

In 1816: Fort Blount revolt Three hundred slaves and about 20 Native American allies hold Fort Blount on Apalachicola Bay, Florida for several days before being attacked by U.S. troops.

American Slave Revolts

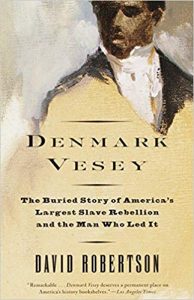

Denmark Vesey

May 30, 1822: Denmark Vesey’s revolt. Vesey had won a lottery and purchased his emancipation in 1800. He was working as a carpenter in Charleston, South Carolina when he started to plan a massive slave rebellion—one of the most elaborate plots in American history—involving thousands of slaves on surrounding plantations, organized into cells. They planned to start a major fire at night and then kill the slave owners and their families. the plan was foiled when a black house servant named George Wilson informed his master of the pending revolt. Charleston authorities promptly arrested and interrogated dozens of suspected conspirators. Mr. Vesey was captured on June 22 and tortured but he refused to identify his comrades.

A total of 131 men was arrested; 67 were convicted and 35, including Denmark Vesey, were executed. The city destroyed Mr. Vesey’s church building. Mr. Vesey and his followers inspired abolitionists and black soldiers through the Civil War.

June 17, 2015: Dylann Storm, Roof, 21, opened fire at Emanuel African Methodist Episcopal Church (Charleston, SC) around 9 p.m. and began shooting, killing nine people before fleeing. He was captured several hours later.

Police chief, Greg Mullen, called the shooting a hate crime.

“This is a tragedy that no community should have to experience,” he said. “It is senseless and unfathomable that someone would go into a church where people were having a prayer meeting and take their lives.” Eight people died at the scene, Mullen said. Two people were taken to the Medical University of South Carolina, and one of them died on the way.

In 1822, one of the church’s co-founders, Denmark Vesey, tried to foment a slave rebellion in Charleston, the church’s website says. The plot was foiled by the authorities and 35 people were executed, including Mr. Vesey.

American Slave Revolts

Underground Railroad

From 1831–1862: The Underground Railroad Approximately 75,000 slaves escape to the North and to freedom via the Underground Railroad, a system in which free African American and white “conductors,” abolitionists and sympathizers help guide and shelter the escapees.

American Slave Revolts

Amistad revolt

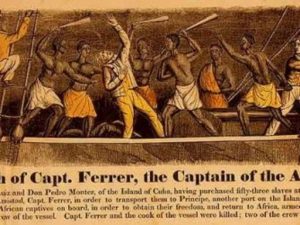

July 2, 1839: Joseph Cinqué led fifty-two fellow captive Africans, recently abducted from the British protectorate of Sierra Leone by Portuguese slave traders, in a revolt aboard the Spanish schooner Amistad. The ship’s navigator, who was spared in order to direct the ship back to western Africa, managed, instead, to steer it northward. When the Amistad was discovered off the coast of Long Island, New York, it was hauled into New London, Connecticut by the U.S. Navy.

President Martin Van Buren, guided in part by his desire to woo pro-slavery votes in his upcoming bid for reelection, wanted the prisoners returned to Spanish authorities in Cuba to stand trial for mutiny. A Connecticut judge, however, issued a ruling recognizing the defendants’ rights as free citizens and ordering the U.S. government to escort them back to Africa. John

August 26, 1839: Americans captured the Amistad (“Friendship”), a Spanish slave ship seized by the 54 Africans who had been carried as cargo on board, which had landed on Long Island, N.Y. At the time, the transportation of slaves from Africa to the U.S. was illegal so the ship owners lied and said the Africans had been born in Cuba.

March 9, 1841: In the Amistad case the U.S. government eventually appealed the case to the Supreme Court. Former president John Quincy Adams, who represented the Amistad Africans in the Supreme Court case, argued in his defense that it was the illegally enslaved Africans, rather than the Cubans, who “were entitled to all the kindness and good offices due from a humane and Christian nation.”

The Amistad survivors were aided, in their defense, by the American Missionary Association, an organization affiliated with the effort to colonize freed slaves overseas. African-American Mosaic includes information about the history of the colonization movement, the colonization of slaves in Liberia, and personal stories of former slaves who chose to move overseas.

The Supreme Court issued a ruling freeing the remaining thirty-five survivors of the Amistad mutiny. Although seven of the nine justices on the court hailed from Southern states, only one dissented from Justice Joseph Story’s majority opinion. Private donations ensured the Africans’ safe return to Sierra Leone in January 1842.

Adams’s victory in the Amistad case was a significant success for the abolition movement.

American Slave Revolts

Slave ship Creole

November 7, 1841: a slave revolt occurred on a slave trader ship, the ‘Creole,’ which was en route from Hampton, Va., to New Orleans, La.,. Slaves overpowered crew and sailed vessel to Bahamas where they were granted asylum and freedom.

American Slave Revolts

Ellen Craft and William

December 25, 1848: Ellen Craft and William were slaves from Macon, Georgia who escaped to the north in December 1848 by traveling openly by train and steamboat, arriving in Philadelphia on Christmas Day. She posed as a white male planter and he as her personal servant. Their daring escape was widely publicized, making them among the most famous of fugitive slaves. Abolitionists featured them in public lectures to gain support in the struggle to end the institution. As the light-skinned mixed-race daughter of a mulatto slave and her white master, Ellen Craft used her appearance to pass as a white man, dressed in appropriate clothing.

American Slave Revolts

Harriet Tubman

In 1849: Harriet Tubman escaped from slavery in Maryland. She became one of the best-known “conductors” on the Underground Railroad, returning to the South 19 times and helping more than 300 slaves escape to freedom.

American Slave Revolts

Compromise of 1850

Fugitive Slave Law

September 18, 1850: Congress passed the Fugitive Slave Law or Fugitive Slave Act as part of the Compromise of 1850 between Southern slave-holding interests and Northern Free-Soilers. This was one of the most controversial acts of the 1850 compromise and heightened Northern fears of a “slave power conspiracy”. It declared that all runaway slaves were, upon capture, to be returned to their masters. Abolitionists nicknamed it the “Bloodhound Law” for the dogs that were used to track down runaway slaves.

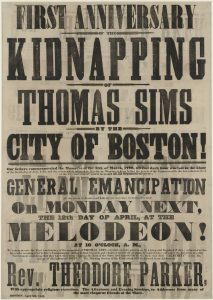

Thomas Sims

April 3, 1851: in early 1851, Thomas Sims, a slave from Savannah, Georgia, successfully escaped and fled to Boston, Massachusetts, where slavery had been abolished. Only a few weeks later, on April 3, 1851, Sims was arrested by a United States Marshal and members of the local police force and taken to the federal courthouse. Fearing riots or an escape attempt, authorities surrounded the courthouse with chains and a heavy police force.

The morning after his capture, attorneys for James Potter, the man who purported to own Sims, presented a complaint to the United States Commissioner. After a short proceeding in which several individuals testified that Sims was the slave who had escaped from Potter’s possession, the Commissioner issued an order remanding Sims back to Georgia. Sims sought review from both the Massachusetts Supreme Court and the United States District Court in Boston, but was unsuccessful. On April 12, Sims left Boston and was returned to Savannah, where he promptly received 39 lashes as punishment for seeking freedom. The marshals who escorted Sims to Georgia received praise and a public dinner for their service.

After the Emancipation Proclamation and in the midst of the Civil War, Thomas Sims again escaped from slavery in 1863, this time fleeing Vicksburg, Mississippi, to return to Boston.

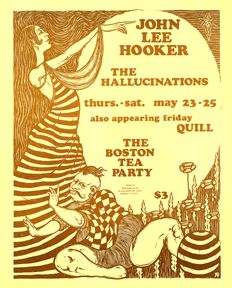

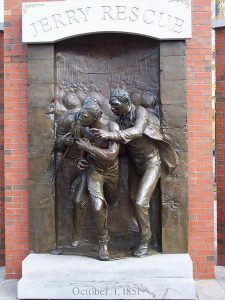

Syracuse, NY

October 1, 1851: citizens of Syracuse, N.Y., broke into the city’s police station and freed William Henry (known as Jerry), a runaway slave who had been working as a barrel-maker. A group of black and white men created a diversion and managed to free Jerry, but he was later rearrested. At his second hearing, a group of men, their skin color disguised with burnt cork, forcibly overpowered the guards with clubs and axes, and freed Jerry a second time. He was then secretly taken over the border to Canada.

American Slave Revolts

John Brown

Harper’s Ferry

October 16 – 17, 1859: Harper’s Ferry attack Led by abolitionist John Brown: a group of slaves and white abolitionists staged an attack on Harper’s Ferry, Virginia. They capture the federal armory and arsenal before the insurrection was halted by local militia under the leadership of Robert E Lee. The raid hastens the advent of the Civil War, which started two years later.

October 25 – November 2, 1859: trial of John Brown.

Hung

December 2, 1859: militant abolitionist John Brown was hanged for murder and treason in the wake an unsuccessful attack on the US armory at Harper’s Ferry, Virginia. An interesting fact is that, the evening before Brown was executed, a group of soldiers slept in the courtroom. One of them was John Wilkes Booth.