American Lynching 4

1934 – present

This is the fourth of four blog entries on Lynching in America (see Never Forget, AL2, and AL3 for the previous entries).

While lynching Blacks may have “ended” in the the 20th century, the inordinate number of Blacks killed has continued. The Black Lives Matter movement of the 21st century–…working for a world where Black lives are no longer systematically targeted for demise–attests to that.

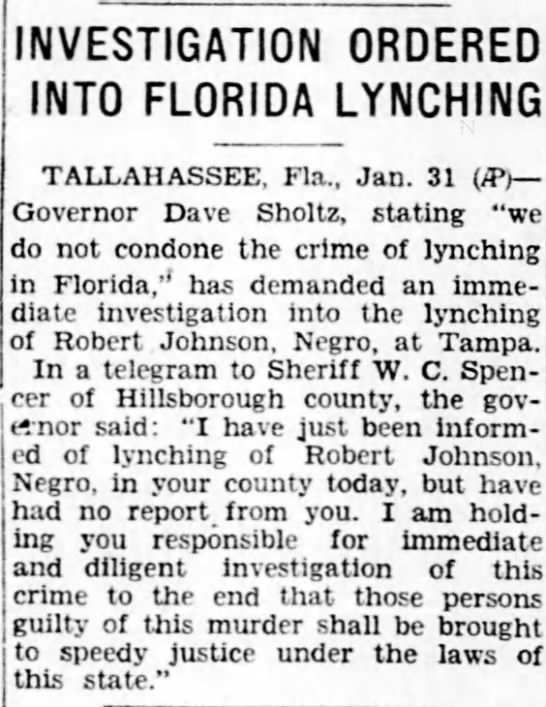

Robert Johnson lynched

January 30, 1934: Deputy Constable Thomas Grave, assigned to move Robert Johnson (see Jan 28), decided to do so after midnight; this was not standard procedure, and Graves later claimed he opted for a late night transfer to avoid waking up early in the morning. Around 2:30 a.m. on January 30th, Graves placed Johnson in the front seat of the police car and began driving to the county jail; on the way, Graves’s vehicle was stopped by three cars full of white men who allegedly disarmed Graves and made him lie face down in the backseat of his car while they kidnapped Robert Johnson.

The mob carried Johnson off to a wooded part of town along the Hillsborough River near Sligh Avenue, where about thirty people were gathered to watch the lynching. Johnson was killed with four shots to the head and one to the body, all fired from the pistol the mob had taken from Deputy Constable Graves.

Governor David Sholtz called for an investigation of the lynching and a grand jury was convened. Though Deputy Constable Graves testified that he was beaten by the mob, the grand jury noted that he bore no bruises or other signs of injury. Nevertheless, the grand jury’s investigation didn’t produce any charges of conspiracy, and no one was prosecuted for Robert Johnson’s murder. [EJI article]

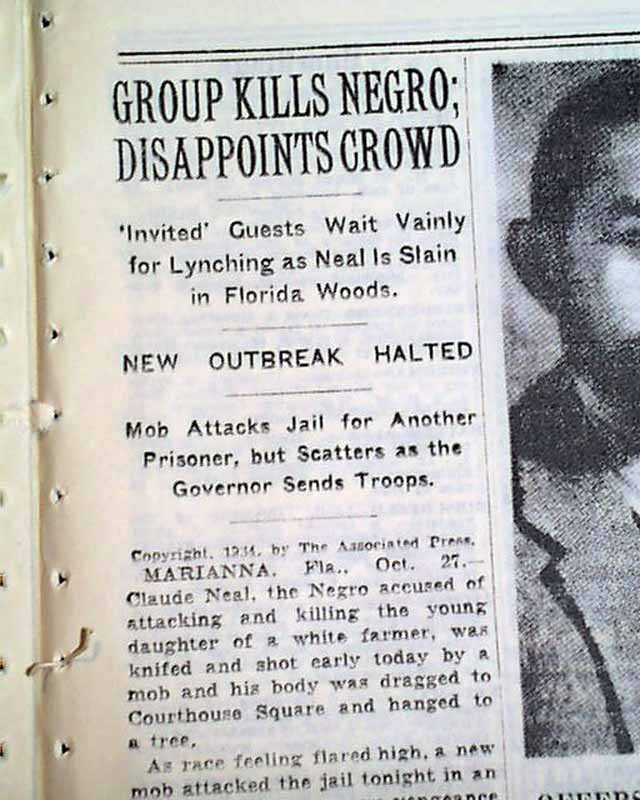

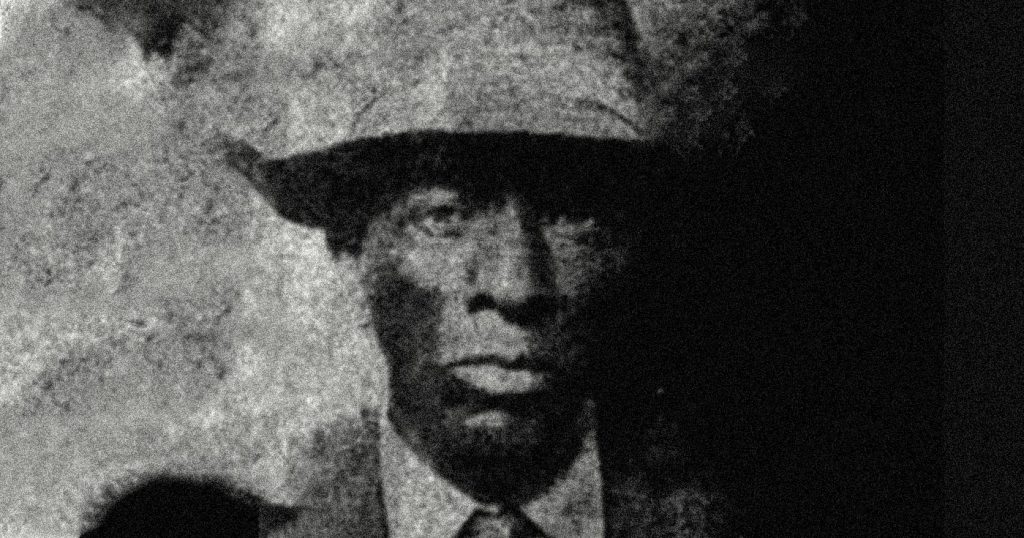

Claude Neal lynched

October 26, 1934: on Thursday, October 18, 1934. Lola Cannidy left her home about noon to water the family livestock. The young white woman never returned. Her mutilated body was found the next morning on a wooded hillside near her home.

Two hours later, Claude Neal, a farmhand who lived across the road from the Cannidy home, was arrested and charged with her rape and murder.

After his arrest, Neal was immediately moved to the neighboring town of Chipley. But when an angry crowd began to gather the sheriff to moved Neal to Panama City, florida. Neal was moved several more times before ending up over 200 miles away in Brewton, Alabama. But it wasn’t far enough.

On the morning of October 26, a mob of more than 100 people showed up at the Brewton jail and hauled Neal back to Marianna. They announced their intention to lynch Neal between 8 and 9 p.m. Friday night – an advance notice of 12 hours.

News of the upcoming lynching spread quickly. Newspapers and radio stations not only in Florida, but across the nation, reported that the lynching was going to take place. And despite the flood of telegrams requesting him to step in, Florida governor Dave Sholtz declined to do so, stating that local authorities had the situation under control.

By the time Friday evening came around, a large crowd of several thousand people had gathered outside the Cannidy farm to observe and participate in the lynching. But the size of the mob began to make the men holding Neal nervous. So the “Lynch Committee of Six,” as the group called itself, decided to take him to another location where they would have better control over how the lynching was carried out.

According to eyewitness accounts and newspaper reports, it was a drawn out and torturous process. Soon after arriving at the chosen spot, Neal was castrated. His torso was cut and stabbed with knives and sticks. His fingers and toes were cut off and the remainder of his body burned with hot irons. One newspaper account states there were 18 bullet holes in Neal’s chest, head and abdomen.

Neal’s body was then tied to the rear of an automobile and dragged to the Cannidy farm, where women and children participated in the final acts of mutilation. The body was then hung from an oak tree on the courthouse lawn. Photos were taken and later sold for 50 cents a piece. Neal’s fingers and toes were reportedly exhibited as souvenirs.

The local sheriff cut the body down the following morning. A mob soon formed demanding that it be hung up again. The sheriff refused, the mob descended upon the courthouse. The mob then dispersed into the city streets and began attacking the remaining blacks in town. [PBS story]

American Lynching 4

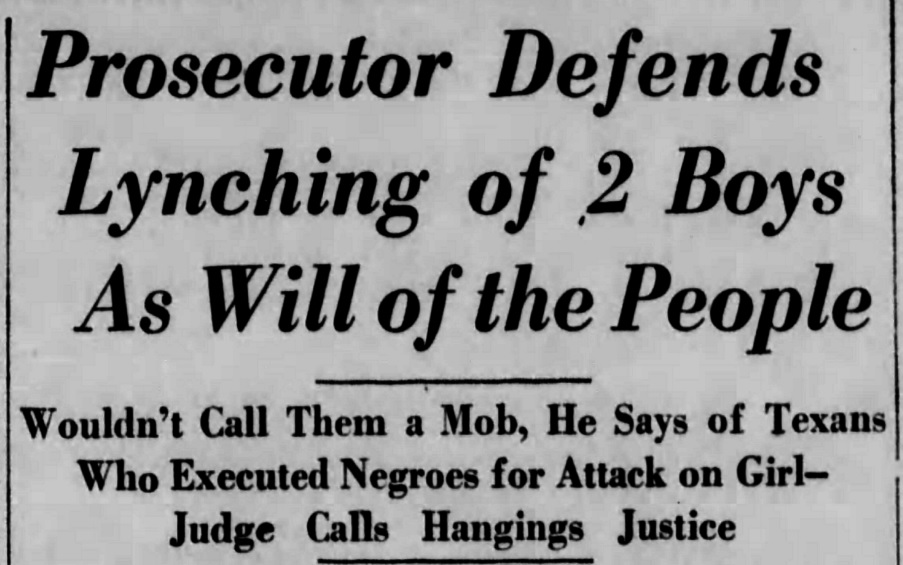

Ernest Collins & Benny Mitchell lynched

November 12, 1935: two teenage black boys – fifteen-year-old Ernest Collins and sixteen-year-old Benny Mitchell – were killed in Colorado County, Texas, in a public spectacle lynching committed by a mob of at least 700 white men and women. Afterward, officials called the lynching “justice,” and no one in the mob was punished. [EJI article]

American Lynching 4

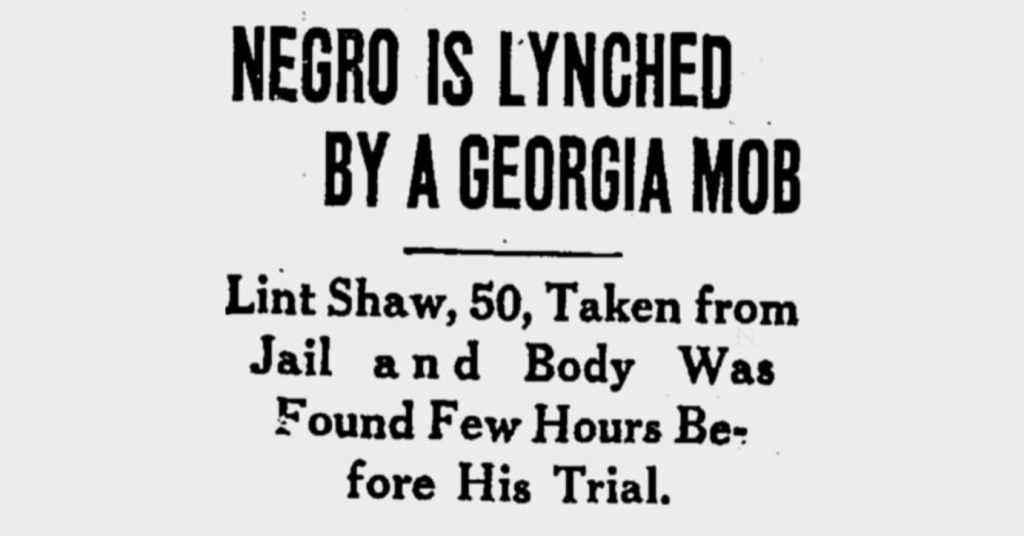

Lint Shaw lynched

April 28, 1936: a 45-year-old black farmer named Lint Shaw was shot to death by a mob of forty white men in Colbert, Georgia – just eight hours before he was scheduled to go on trial on allegations of attempting to assault two white women. [EJI article]

American Lynching 4

Elbert Williams lynched

June 20, 1940: a group of white men led by the local sheriff and the night marshal abducted NAACP leader Elbert Williams from his home in Brownsville, Tennessee. Three days later, Mr. Williams’s lifeless and brutalized body was found in the nearby Hatchie River. He was thirty-one years old.

In the months following the lynching of Elbert Williams, up to forty more black families were permanently driven from the community under threats of violence from the white mob. African Americans who remained in Brownsville were prohibited from meeting in groups, even for church services, and two African American men were beaten to death after being arrested by the same night marshal who had helped to abduct Williams. [EJI article]

American Lynching 4

Jesse Thornton lynched

June 21, 1940: twenty-six-year-old black man Jesse Thornton addressed a passing police officer by his name, Doris Rhodes. When the officer, a white man, overheard Mr. Thornton and ordered him to clarify his statement, Thornton attempted to correct himself by referring to the officer as “Mr. Doris Rhodes.” The officer hurled a racial slur at Mr. Thornton while knocking him to the ground and arresting him. Rhodes then walked Thornton into the city jail as a mob of white men formed just outside.

Thornton tried to escape and managed to flee a short distance while the mob quickly pursued, firing gunshots and throwing bricks, bats, and stones at him. Thornton was injured by gunfire and eventually collapsed. The mob dumped him into a truck and drove to an isolated street where he was dragged into a nearby swamp and shot again. Thornton’s decomposing, vulture-ravaged body was found a week later by a local fisherman in the Patsaliga River, near Tuskegee Institute.

Dr. Charles A.J. McPherson, a local leader in the Birmingham branch of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People, wrote a detailed report on Thornton’s lynching. Thurgood Marshall, then an attorney with the NAACP, provided the Department of Justice with the report and requested a federal investigation. The Justice Department instructed the Federal Bureau of Investigation to determine whether law enforcement or other officials were complicit in the lynching but there is no record that anyone was ever prosecuted for Mr. Thornton’s murder. [Northeastern article]

American Lynching 4

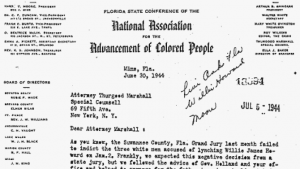

Willie James Howard lynched

January 2, 1944 15-year-old Willie James Howard, a black boy, was kidnapped and lynched by three white men in Suwannee County, Florida, after being accused of sending a love note to the daughter of one of the men.

During Christmas 1943, Willie Howard sent cards to all of his co-workers at the Van Priest Dime Store in Live Oak, Florida. Unlike the other cards, Willie’s card to Cynthia Goff, a white store employee, revealed a youthful crush. His greeting expressed hope that white people would someday like black people and concluded: “I love your name. I love your voice. For a S.H. [sweetheart] you are my choice.”

After reading the card, Cynthia’s father, Phil Goff, brought two friends to the Howard home and demanded to see Willie. Despite his mother’s pleading, the men dragged Willie away, and then kidnapped Willie’s father, James Howard, from work. The men drove the two Howards to the embankment of the Suwanee River, bound Willie’s hands and feet, stood him at the edge of the water, and told him to either jump or be shot. Willie jumped into the cold water below and drowned while his father was forced to watch at gunpoint. Willie’s body was pulled from the river the next day.

Goff and his accomplices admitted to the local sheriff that they took Willie to the river to punish him, but claimed the teen had become hysterical and jumped into the water unprovoked at the thought of being whipped by his father. Fearful for his own life and the other members of his family, James Howard signed a statement supporting Goff’s account. He and his family fled Live Oak three days later. [PBS report]

American Lynching 4

Eldridge Simmons lynched

March 26, 1944: a Rev. Simmons controlled more than 270 acres of debt-free Amite County (Mississippi) land that his family had owned since 1887. A farmer and minister, Rev. Simmons worked the land with his children and grandchildren, producing crops and selling the property’s lumber.

In 1941, a rumor spread that there was oil in southwest Mississippi. A group of six white men decided they wanted the Simmons’ land and warned Rev. Simmons to stop cutting lumber. Rev. Simmons consulted a lawyer to work out the dispute and ensure his children would be the sole heirs to the property.

On Sunday 26 March 1944, a group of white men arrived at the home of Rev. Simmons’s eldest son, Eldridge, and told him to show them the property line. He agreed to do so, but while Eldridge Simmons rode with the men in their vehicle, they began to beat him, and shouted that the Simmons family thought they were “smart niggers” for consulting a lawyer. The men then dragged Rev. Simmons from his home about a mile away and began beating him, too. They drove both Simmons men further onto the property and ordered Rev. Simmons out of the car, then killed him brutally–shooting him three times and cutting out his tongue.

After Eldridge and the rest of the Simmons family buried Rev. Simmons, they fled their land in fear. The white men who committed the lynching took possession of the land; only one of the six men was ever prosecuted for the murder, and he was ultimately acquitted by an all-white jury. [EJI article]

American Lynching 4

Maceo Snipes lynched

July 18, 1946: a white mob shot and killed Maceo Snipes, a 37-year-old Black veteran, at his home in Butler, Georgia. A day earlier, Mr. Snipes had exercised his Constitutional right to vote in the Georgia Democratic Primary, becoming the only Black man to vote in the election in Taylor County. For this he was targeted and lynched.

Snipes had served in the U.S. Army for two and a half years during World War II and, after receiving an honorable discharge, had returned home to Taylor County, Georgia, to work as a sharecropper with his mother. Mr. Snipes’s family later recalled that he had received threats from the Ku Klux Klan in the days leading up to the election, but he still bravely went to vote in the gubernatorial primary on July 17, 1946.

When local authorities investigated Snipes’s shooting, Edward Williamson admitted to killing him, but claimed Mr. Snipes had pulled a knife on him when he went to the Snipes home to collect a debt. A member of a prominent white family in Taylor County, Mr. Williamson’s story was believed at face value despite contrary assertions in Mr. Snipes’s deathbed statement and his mother’s witness testimony. The coroner’s jury ultimately ruled that the shooting had been in “self-defense,” and no one was ever held accountable for Mr. Snipes’s death. [EJI article]

Lynching at Moore’s Fort Bridge

July 25, 1946: the lynching of two married African-American couples, known in some circles as the “Lynching At Moore’s Ford Bridge,” took place in northern Georgia. An angry mob of white men attacked the couples, with one of the wives seven months pregnant and a man in the group a World War II Army veteran. George Dorsey, the veteran who had been back in the States just nine months after serving in the Pacific, and his wife, Mae, worked as sharecroppers. Roger and Dorothy Malcolm also worked on the farm with the Dorseys and were expecting a child.

The FBI was sent to the town of Monroe, but the investigation yielded little as no one stepped forward to offer assistance or testimony. (2017 NC News article on re-enactment)

American Lynching 4

NAACP report

January 3, 1947: an NAACP report said 1946 was “one of the grimmest years in the history of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People.” The report deplored “reports of blow torch killing and eye-gouging of Negro veterans freshly returned from a war to end torture and racial extermination” and said “Negroes in America have been disillusioned over the wave of lynchings, brutality and official recession from all of the flamboyant promises of post war democracy and decency.”

American Lynching 4

Anti-lynching law platform

July 14, 1948: President Harry Truman and the Democratic Party adopted a platform that called for a federal anti-lynching law, the abolition of poll taxes and the desegregation of armed forces. Three days later, Southern “Dixiecrats” held their own convention and nominated South Carolina Governor Strom Thurmond for president. [text of platform]

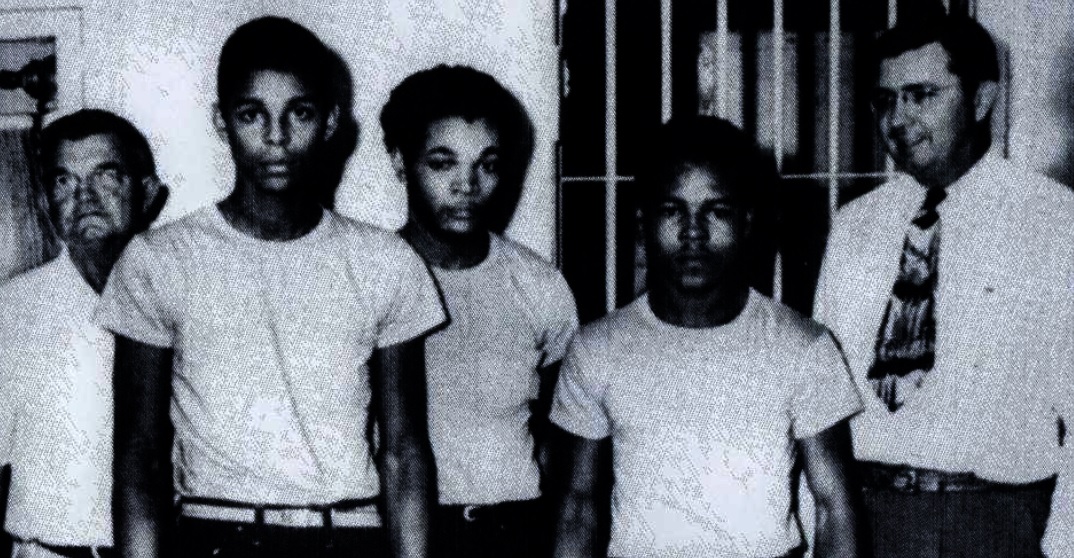

Ernest Thomas Killed

July 26, 1949: a mob of hundreds of white men tracked down and shot Ernest Thomas over 400 times while he was asleep under a tree in Madison County, Florida. Two days after being killed by the mob, a coroner’s jury ruled that Mr. Thomas’s death was “justifiable homicide.”

Thomas was one of the so-called Groveland Four, three young Black men and one 16-year-old Black boy, who in 1949 were falsely accused of raping 17-year-old Norma Padgett and assaulting her husband in Groveland, Florida. [EJI story]

72 Years Later

On November 22, 2021, Administrative Judge Heidi Davis officially exonerated Ernest Thomas, Samuel Shepherd, Charles Greenlee, and Walter Irvin.

At the request of the local prosecutor, Davis dismissed the indictments Thomas and Shepherd and set aside the convictions and sentences of Greenlee and Irvin.

“We followed the evidence to see where it led us and it led us to this moment,” said Bill Gladson, the local state attorney, following the hearing in the same Lake County courthouse where the original trials were held. Gladson, a Republican, moved last month to have the men officially exonerated. [NPR story]

American Lynching 4

Ruby Hurley

April 28, 1951: Ruby Hurley opened the first permanent office of the NAACP in the South, setting it up in Birmingham, Ala. Her introduction to civil rights activism began when she helped organize Marian Anderson’s 1939 concert at the Lincoln Memorial. Four years later, she became national youth secretary for the NAACP. She helped investigate lynchings across the South and received many threats, including a bombing attempt on her home. In 1956, she left Birmingham for Atlanta after Alabama barred the NAACP from operating. She served as a mentor for Vernon Jordan and retired two years before dying in 1980. In 2009, she appeared on a postage stamp. (women’s history dot org bio)

American Lynching 4

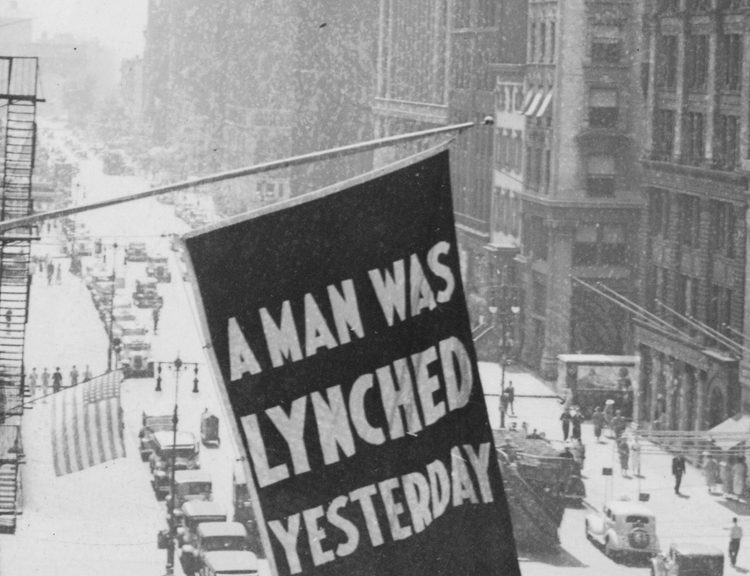

A year without a lynching

December 30, 1952: for the first time in seventy years, a full year passed with no recorded incidents of lynching. Defined as open, non-judicial murders carried out by mobs, lynching befell people of many backgrounds in the United States but was a frequent tool of racial terror used against black Americans to enforce and maintain white supremacy.

Prior to 1881, reliable lynching statistics were not recorded. But the Chicago Tribune, the NAACP, and the Tuskegee Institute began keeping independent records of lynchings as early as 1882. As of 1952, these authorities reported that 4726 persons had been lynched in the United States over the prior seventy years and 3431 of them were African American. During some years in American history it was not unusual for all lynching victims to be African American.

Lynching in the United States was most common in the later decades of the nineteenth century and early decades of the twentieth century, during post-reconstruction efforts to re-establish a racial hierarchy that subordinated and oppressed black people. Before the lynching-free year of 1952, annual lynching statistics were exhibiting significant reductions. Between 1943 and 1951 there were twenty-one lynchings reported nationwide, compared to 597 between 1913 and 1922. After 1952, the number of lynching incidents recorded annually continued to be zero or very low and the tracking of lynchings officially ended in 1968.

Though the diminished frequency of lynching signaled by the 1952 report was encouraging, the Tuskegee Institute warned that year that “other patterns of violence” were emerging, replacing lynchings with legalized acts of racialized inhumanity like executions, as well as more anonymous acts of violence such as bombings, arson, and beatings. Similarly, a 1953 editorial in the Times Daily of Florence, Alabama, noted that, though the decline in lynching was good news, the proliferation of anti-civil rights bombings demonstrated the South’s continued need for “education in human relations.”

American Lynching 4

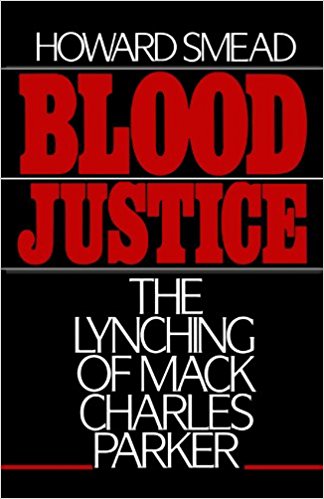

Mack Charles Parker lynched

April 25, 1959: three days before his scheduled trial, Mack Charles Parker, a 23-year-old African American truck driver, was lynched by a hooded mob of white men in Poplarville, Mississippi. Parker had been accused of raping a pregnant white woman and was being held in a local jail. The mob took him from his cell, beat him, took him to a bridge, shot and killed him, then weighed his body down with chains and dumped him in the river. Many people knew the identity of the killers, but the community closed ranks and refused to talk. Echoing the Till case, the FBI would investigate and identify at least 10 men involved, but the U.S. Department of Justice would rule there were no federal grounds to make an arrest and press charges. Two grand juries — one county and one federal — adjourned without indictments. (Black Past article)

American Lynching 4

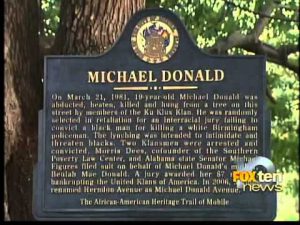

Michael Donald

Lynched

March 21, 1981: Mobile, Alabama. Henry Hays (age 26), and James Llewellyn “Tiger” Knowles (age 17) kidnap, beat, strangle, and slit the throat of Michael Donald before hanging him from a tree. Local police initially stated that Donald had been killed as part of a drug deal gone wrong. (see June 6, 1997). Donald, an African-American, had been walking back from a store and randomly selected by Ku Klux Klan members Hays and Knowles. [EJI article]

Indictments

June 16, 1983: authorities charged Ku Klux Klansmen James Knowles, 19 years old, Henry Hays, 28, and Benjamin Cox March 20, 1981 death by beating of black teenager Michael Donald. [NYT article]

Hays was executed on June 6, 1997. Hays is the only known KKK member to have been executed in the 20th century for the murder of an African American. Knowles was released on parole in 2010. [Wiki article]

Southern Poverty Law Centre

In February 1987: with the support of Morris Dees and Joseph J. Levin at the Southern Poverty Law Centre (SPLC), Beulah Mae Donald, the mother of slain Michael Donald sued the United Klans of America. An all-white jury found the Klan responsible for the lynching of Michael Donald and ordered it to pay 7 million dollars. This resulted the Klan having to hand over all its assets including its national headquarters in Tuscaloosa.

Michael Donald lynching

June 6, 1997: Henry Hays, one of the two murderers of Michael Donald in 1981, executed in the electric chair. Hays was the only Ku Klux Klan member to be executed for the murder of a black man in the 20th century. Hay’s accomplice, Llewellyn Knowles had been sentenced to life in prison after testifying against Hays. [NYT article]

American Lynching 4

Tulsa Lynchings Reparations

February 21, 2001: after the Oklahoma State Legislature authorized a commission to study the Tulsa Riot of 1921, the report recommended actions for substantial restitution; in order of priority (Tulsa history article):

- Direct payment of reparations to survivors of the 1921 Tulsa race riot;

- Direct payment of reparations to descendants of the survivors of the Tulsa race riot;

- A scholarship fund available to students affected by the Tulsa race riot;

- Establishment of an economic development enterprise zone in the historic area of the Greenwood district; and

- A memorial for the reburial of the remains of the victims of the Tulsa race riot.

American Lynching 4

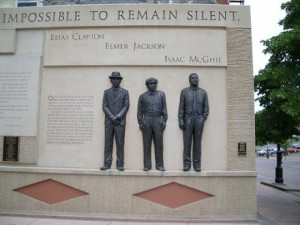

Duluth, MN lynching

October 10, 2003: the June 15, 1920 Duluth, MN lynching was commemorated by dedicating a plaza including three seven-foot-tall bronze statues to the three men who were killed. The statues were part of a memorial across the street from the site of the lynchings. The Clayton Jackson McGhie Memorial was designed and sculpted by Carla J. Stetson, in collaboration with editor and writer Anthony Peyton-Porter.

At the memorial’s opening, thousands of citizens from Duluth and surrounding communities gathered for a ceremony. The final speaker at the ceremony was Warren Read, the great-grandson of one of the most prominent leaders of the lynch mob:

“It was a long held family secret, and its deeply buried shame was brought to the surface and unraveled. We will never know the destinies and legacies these men would have chosen for themselves if they had been allowed to make that choice. But I know this: their existence, however brief and cruelly interrupted, is forever woven into the fabric of my own life. My son will continue to be raised in an environment of tolerance, understanding and humility, now with even more pertinence than before.”

American Lynching 4

US Senate apologizes

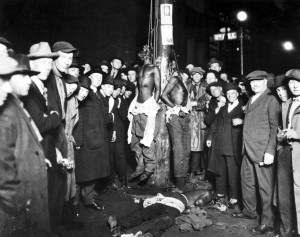

June 13, 2005: between 1882 and 1968, approximately 4743 people were lynched in America, and nearly three-quarters of those lynching victims were black. Lynchings were extrajudicial and heinous killings, usually intended to warn other blacks not to transgress racialized social, political, and economic boundaries. Victims often were hanged, but sometimes were shot, stabbed, or burned alive. Their murders ranged from community spectacles at which hundreds of participants ate picnics and took body parts and photo postcards as souvenirs to low-profile concealed murders involving as few as two assailants.

During the lynching era, seven United States presidents exhorted Congress to pass legislation authorizing federal prosecution of lynch mobs. Two hundred anti-lynching bills were introduced but only three passed the House of Representatives and none passed the Senate due to Southern conservatives’ successful filibusters. In the absence of federal protection, and amidst the inaction of local state courts, lynchings persisted for decades.

On June 13, 2005, the United States Senate formally apologized for failing to pass anti-lynching legislation. Resolution sponsor Senator George Allen (R-VA) expressed his regret for “the failure of the Senate to take action when action was most needed,” while co-sponsor Senator Mary Landrieu (D-LA) declared, “It’s important that we are honest with ourselves and that we tell the truth about what happened.” Nearly eighty other senators co-sponsored the resolution.

Hundreds of relatives of lynching victims were present to witness the apology, as was ninety-one-year-old James Cameron, largely considered the only known survivor of a lynching attempt. In 1930, Mr. Cameron was sixteen when he and two friends were seized by a white lynch mob in Marion, Indiana, and both of his friends were hung and killed. Mr. Cameron was cut down and released. No one was ever arrested or charged.

American Lynching 4

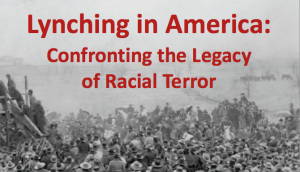

Lynching in America

February 10, 2015: The Equal Justice Initiative (EJI) released Lynching in America: Confronting the Legacy of Racial Terror, which documented EJI’s multi-year investigation into lynching in twelve Southern states during the period between Reconstruction and World War II. EJI researchers documented 3959 racial terror lynchings of African Americans in Alabama, Arkansas, Florida, Georgia, Kentucky, Louisiana, Mississippi, North Carolina, South Carolina, Tennessee, Texas, and Virginia between 1877 and 1950 – at least 700 more lynchings of black people in those states than previously reported in the most comprehensive work done on lynching to date. (EJI pdf of report)

Emmett Till Anti-Lynching Act

March 7, 2021: the Senate unanimously passed a bill that criminalized lynching and made it punishable by up to 30 years in prison. It sailed through the House of Representatives last month, and President Biden was expected to sign it.

While it eased through both chambers of Congress this time with virtually no opposition, the path to passage took more than 100 years and 200 failed attempts.

Under the bill, named the Emmett Till Anti-Lynching Act after the 14-year-old boy from Chicago who was lynched while visiting family in Mississippi, a crime can be prosecuted as a lynching when a hate crime results in a death or injury, said Rep. Bobby Rush, D-Ill., a longtime sponsor of the legislation.

“Lynching is a longstanding and uniquely American weapon of racial terror that has for decades been used to maintain the white hierarchy,” Rush said in a statement. “Unanimous Senate passage of the Emmett Till Anti-Lynching Act sends a clear and emphatic message that our nation will no longer ignore this shameful chapter of our history and that the full force of the U.S. federal government will always be brought to bear against those who commit this heinous act.” [NPR article] (next BH, see ; next Lynching, see ; for expanded chronology, see AL 4 )

Also see…

American Lynching 4

Emmett Till Anti-Lynching Act

March 28, 2022: President Joe Biden signed the Emmett Till Anti-Lynching Act into law that made lynching a federal hate crime, acknowledging how racial violence has left a lasting scar on the nation and asserting that these crimes are not a relic of a bygone era.

The President said, “Lynching was pure terror to enforce the lie that not everyone … belongs in America, not everyone is created equal. Terror, to systematically undermine hard-fought civil rights. Terror, not just in the dark of the night but in broad daylight. Innocent men, women and children hung by nooses in trees, bodies burned and drowned and castrated.” [CNN article]