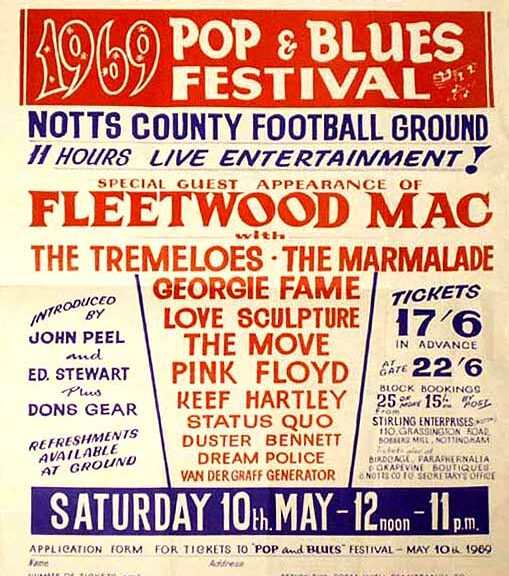

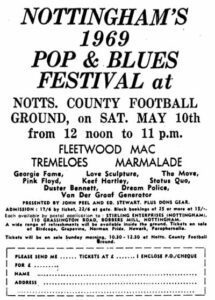

Nottingham Pop & Blues Festival

May 10, 1969

Notts County Football Ground,

Nottingham, Nottinghamshire

1969 festival #4

Although Nottingham was only a one-day festival, it advertised that it would have 12 performances during its 11 hours, about a third of that Woodstock thing a few months later.

Although Nottingham was only a one-day festival, it advertised that it would have 12 performances during its 11 hours, about a third of that Woodstock thing a few months later.

Because I cannot find much specific information about Nottingham, as I had to do with Rockarama, 1969’s first festival, I will simply give some bios about the bands and include an appropriate YouTube video if possible.

Readers who have links or personal experience with the festival, please comment and I’ll adjust this post. Thanks.

Fleetwood Mac

This performance was one of many on their 1969 Mr Wonderful tour. They had begun the year in Chicago at the Kinetic Playground opening for the Byrds and Muddy Waters. They would end the year at exactly the same place, but this time as a solo. Their schedule that year was grueling to say the least. Band members were Mick Fleetwood, Peter Green, Jeremy Spencer, John McVie, Danny Kirwan.

Nottingham Pop & Blues Festival

Pink Floyd

Pink Floyd. One Pink Floyd data site says that they were there on their The Man and the Journey tour, but that’s it. Another has a setlist:

The Man:

- Grantchester Meadows

- Work

- Teatime

- Biding My Time

- Up the Khyber

- Quicksilver

- Cymbaline

- Grantchester Meadows

The Journey

- Green Is the Colour

- Careful With That Axe, Eugene

- The Narrow Way: Part 3

- The PInk Jungle

- Let There Be More Light

- A Saucerful of Secrets

- Behold the Temple of Light

- Celestial Voices

- (Encore) Interstellar Overdrive.

Nottingham Pop & Blues Festival

Tremeloes

Beatle fans may remember that Decca Records had chosen the Tremeloes over them after their January 1, 1962 audition. The Tremeloes went through various personnel changes by 1969, including the departure of Brian Poole whose name was originally part of the band’s name. Their style certainly fit the “Pop” of this festival’s name. (Call Me) Number One was one of their big hits in 1969. They are still performing, at least some of them are.

Nottingham Pop & Blues Festival

Marmalade

It was the Tremeloes who’d “discovered” the Gaylords and recommended the band to Peter Walsh, their manager. The first thing Walsh did was change their name. Not surprisingly, the name occurred to him during breakfast. The band gained a great reputation, but did not succeed financially. They stuck it out and decided to try a more commercial approach which worked when they covered, before the Beatles’ “White Album” release, Ob-La-Di, Ob-La-Da.” It became a #1 hit in England. For American listener, it was their 1969 song, “Reflections of My Life” that is most remembered.

Nottingham Pop & Blues Festival

Georgie Fame

Fame was a successful musician well-before 1969. He’d had several songs on the British charts. His greatest chart success was in 1967 when “The Ballad of Bonnie and Clyde” became a number one hit in the UK, and No. 7 in the US. Fame continues to play and has a long list of credits.

Nottingham Pop & Blues Festival

Love Sculpture

From AllMusic: A British blues-rock band of the late ’60s that, despite being very good, would normally be relegated to footnote status if it were not for the fact that the lead guitarist of this trio was the soon-to-be-famous Dave Edmunds. Like many similar bands of the times, Love Sculpture was really a showpiece for Edmunds’ guitar-playing talents (which on the first LP are considerable), and little else. The covers are well-chosen, slightly revved-up, but mostly reverent versions of blues classics. They had a fluke hit in 1968 with a cover of the classical piece “Sabre Dance,” rearranged for guitar. After two LPs, Love Sculpture split up in 1970.

Nottingham Pop & Blues Festival

The Move

From AllMusic: The Move were the best and most important British group of the late ’60s that never made a significant dent in the American market. Through the band’s several phases (which were sometimes dictated more by image than musical direction), their chief asset was guitarist and songwriter Roy Wood, who combined a knack for Beatlesque pop with a peculiarly British, and occasionally morbid, sense of humor.

Nottingham Pop & Blues Festival

Keef Hartley Band

Drummer Keef Hartley had been a part of John Mayall’s band before Hartley formed his own band in 1968. True to his humorous relationship with Mayall, the first track on the band’s premiere album, Halfbreed, is called “Hearts and Flowers” in which there is a tongue-in-cheek phone call in which Mayall fires Hartley. As any Woodstock alum knows, the band played at Woodstock, but is one of the lesser known bands who did.

Nottingham Pop & Blues Festival

Status Quo

From AllMusic: Status Quo are one of Britain’s longest-running bands, staying together for over six decades. During much of that time, the group was only successful in the U.K., where they racked up a string of Top Ten singles over the decades. In America, the Quo were ignored after they abandoned psychedelia for heavy boogie rock in the early ’70s. Before that, the band managed to reach number 12 in the U.S. with the psychedelic classic “Pictures of Matchstick Men” (a Top Ten hit in the U.K.). Following that single, the group suffered a lean period for the next few years before the band members decided to refashion themselves as a hard rock boogie band in 1970 with their Ma Kelly’s Greasy Spoon album. The Quo have basically recycled the same simple boogie on each successive album and single, yet their popularity has never waned in Britain. If anything, their very predictability ensured the group a large following.

The band continues to tour and has an informative site. Here is a song from 1968 because it is more familiar to some American listeners.

Nottingham Pop & Blues Festival

Duster Bennett

Definitely reflecting the blues in Nottingham’s day, Anthony Bennett was born in Welshpool, Wales in 1946, and in the mid-60s he relocated to London to study. There was a flourishing Blues club scene in South-West London and soon he began playing there as a one-man-band, billed as Duster Bennett. His skill as a harp player got him some session work, as the Blues sound of The Stones and The Animals meant that even mainstream pop records often had a taste of ‘Mississippi Sax’. In the clubs, Duster sounded a lot like a loose-limbed Jimmy Reed as he played guitar with his harp held in a neck-rack and a bass drum/hi-hat combo, and in 1967 he was signed to Mike Vernon‘s Blue Horizon label. His first album, ‘Smiling Like I’m Happy’ featured help from Peter Green, Mick Fleetwood and John McVie, and songs by Jimmy McCracklin, Magic Sam and Juke Boy Bonner alongside his own material. Duster was a popular act on the Blues scene, with club and concert gigs almost every night, where he was often joined by his girlfriend Stella Sutton on backing vocals, and he opened many tours for visiting American Blues stars. [from All About Blues Music site]

After performing with Memphis Slim on 26 March 1976, in Burslem Stoke on Trent, Bennett was driving home in a Ford Transit van in Warwickshire when he apparently fell asleep at the wheel. The van collided with a truck and Bennett was killed

Nottingham Pop & Blues Festival

Dream Police

From the Rocking Scots site: A very adventurous band in the numbers they covered such as Joni Mitchell’s ‘Carrie’ and Traffic’s ‘No Face, No Name, No number’. The band quickly became one of Scotland’s bigger crowd pullers

Nottingham Pop & Blues Festival

Van Der Graaf Generator

From AllMusic: An eye-opening trip to San Francisco’s Haight-Ashbury during the summer of 1967 inspired British-born drummer Chris Judge Smith to compose a list of possible names for the rock group he wished to form. Upon his return to Manchester University, he began performing with singer/songwriter Peter Hammill and keyboardist Nick Peame; employing one of the names from Judge Smith‘s list, the band dubbed itself Van der Graaf Generator (after a machine that creates static electricity), eventually earning an intense cult following as one of the era’s preeminent art rock groups.

The band, as many bands, had and would undergo many personnel changes and is still active.

Nottingham Pop & Blues Festival

Introduced by…

You will see on the promotional poster that John Peel, Ed. Steward did the introductions.

John Peel

From a BBC site: John Peel was one of Britain’s most loved broadcasters.

With a whiplash wit, a dry delivery and a total adoration and love of music in all its forms, Peel was a true one-off.

There was more to John Peel than spinning discs, curating the famous Peel Sessions and supporting bands with names like You’ve Got Foetus On Your Breath and Napalm Death.

You may not know that he ‘did time’ in the army and he battled bullies at a posh boarding school. Glad to say he came out on top and with a healthy disregard for authority.

Ed Stewart

From a BBC site: He was one of the first presenters on Radio 1 when it launched in 1967, and went on to become a regular Top of the Pops presenter in the 1970s.

He was a regular Radio 2 presenter for 15 years, and during that time broadcast from the summits of Ben Nevis and Snowdon, Mount Vesuvius volcano in Italy, and also live from the Falkland Islands.

Nottingham Pop & Blues Festival

Next 1969 festival: Aldergrove Beach Rock Festival