Elektra Records Jac Holzman

Born September 15, 1931

Follow the Music

Stefano Santucci, a childhood conker buddy and fellow vinyl collector, recommended that I read Follow the Music: The Life and High Times of Electra Records In The Great Years of American Pop Culture by Jac Holzman and Gavan Daws.

He said that it was “…the cat’s pajamas. Highly recommend how this guy Jac Holzman discovered and produced some of the most amazing bands and songwriters, but also found their proper producer and engineers to get their best stuff out…not only the proper sound, but also elected the album art and logos.”

Among Boomers, a common complaint regarding today’s recordings is the size of liner notes while holding a CD or, worse, no liner notes with a download.

Album covers we could read, but today’s font sizes (did anyone even know what the word “font” meant in the 60s?) (if one actually purchases a “hard” copy of a recording and not simply downloads it) are lilliputian.

Elektra Records Jac Holzman

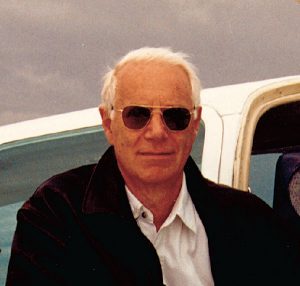

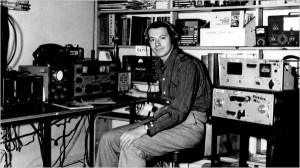

Jac Holzman

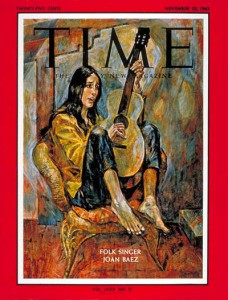

When I did read those covers, I always saw the name Jac Holzman on the back of my Elektra Records and gradually realized that Elektra Records was a company that could be depended upon to produce great music.

Holzman founded Elektra Records on October 10 1950 out of his St John’s College (Maryland) dorm room. (Sounds like Crawdaddy! founder Paul Williams, eh?)

Holzman had $300 bar mitzvah money, but needed $300 more.College friend and Navy vet Paul Rickholt put in his veterans bonus. To make the Elektra logo, Holzman turned two Ms on their side for the Es and used a K instead of a C. Voila.

Holzman was before Sam Phillips’s Memphis Studio.

Before Elvis.

Before Rocket 88.

Before the Beatles were teenagers.

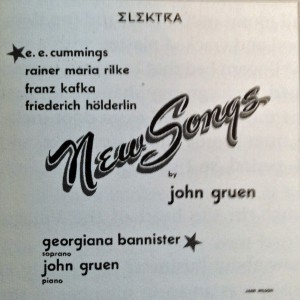

Elektra’s first album was an album of German art poems set to music by John Gruen and sung by Georgiana Bannister. Holzman left St John’s College and stepped into Greenwich Village’s nascent folk scene. He recorded Josh White (folk blues), Jean Ritchie (Appalachian folk) and Theodore Bikel (Israeli folk).

He recorded Judy Collins and Tom Paxton.

Record companies need income and Jac Holzman was creative. He could support the fledgling folk artist because he also released a series of albums aimed at branches of the military and various other groups’ interests and hobbies.

Elektra Records Jac Holzman

Sound effects

According to the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame site: Another of Holzman’s inspirations was a series of sound effects records. The first volume was released in 1960. Numbering 13 in total, they sold well and were extremely popular with the movie industry and radio programmers. Never had such a gallery of sounds and noises, including a definitive car crash, been so painstakingly recorded. Moreover, they were highly profitable because there were no performers’ royalties involved.

Another way he subsidized his Elektra label was by creating Nonesuch records in 1963. He made classical music available by licensing titles from overseas labels and marketing the records at a lower price than American labels selling the same titles.

As the music of the 60’s evolved, so did Elektra. Acoustic folk continued to be part of the label, but electricity too.

The Incredible String Band. David Ackles, Carly Simon. Harry Chapin. Bread. Paul Butterfield Blues Band. Love. The Doors. Clear Light. The MC5. The Stooges. Queen.

Elektra Records Jac Holzman

Rock and Roll Hall of Fame

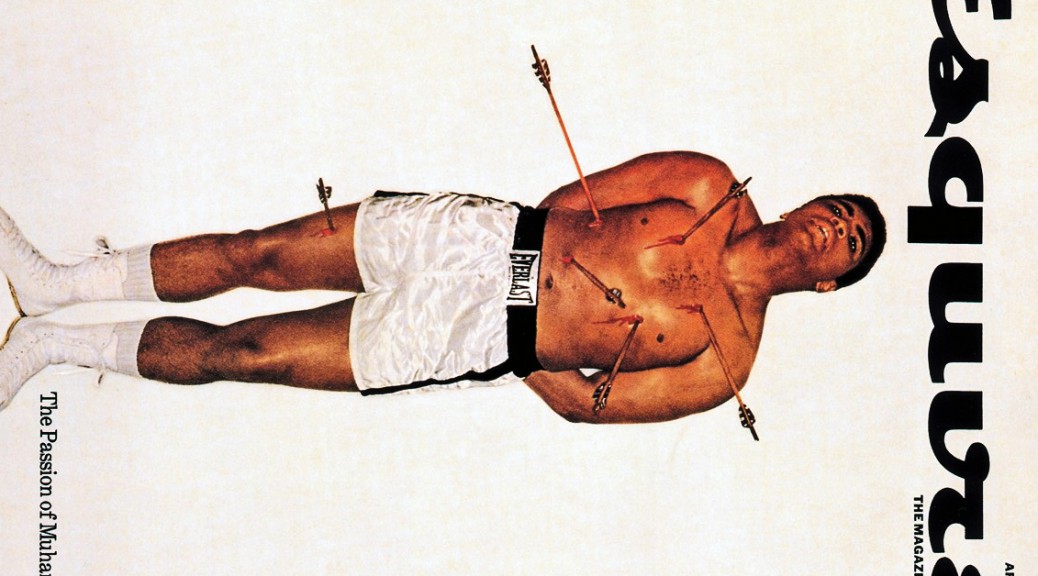

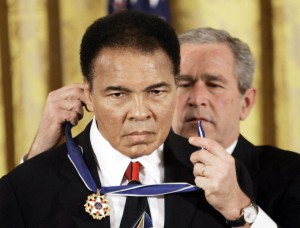

John Densmore spoke at Jac Holzman’s March 14, 2011 Rock and Roll Hall of Fame induction. Densmore said, “Without Jac Holzman, Jim Morrison’s lyrics would not be on the tip of the world’s tongue.”

Music continues to benefit from Holzman. Nowadays he is now Senior Technology Adviser to Warner Music Group as “a wide-ranging technology ‘scout’, exploring new digital developments and identifying possible partners.”

References: Rock and roll Hall of Fame bio >>> R & R H o F Derek Sivers site >>> Sivers