KKK Kills Activist Viola Liuzzo

Viola Fauver Gregg

Viola Fauver Gregg was born on April 11, 1925 in California, PA. Her family was poor and often moved to find work.

KKK Kills Activist Viola Liuzzo

Activist murdered

It would be the last speech she heard.

Using her car, Viola Liuzzo and Leroy Moton, a 19-year-old black man who had also marched and assisted with the March to Montgomery, were helping to shuttle people from Montgomery back to Selma.

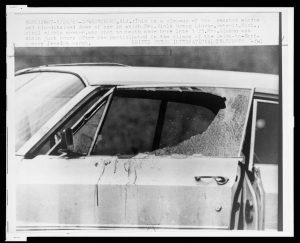

After dropping passengers in Selma, she and Moton headed back to Montgomery. On the way another car pulled alongside and a passenger in that car shot directly at Liuzzo, hitting her twice in the head, and killing her instantly. Moton was uninjured.

KKK Kills Activist Viola Liuzzo

Arrests immediate

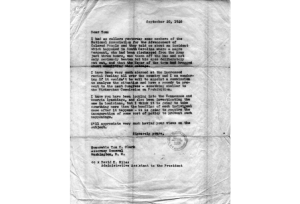

Within 24 hours President Lyndon Johnson appeared on national TV to announce the arrest of Collie Wilkins (21), William Eaton (41) and Eugene Thomas (41) and Gary Rowe (34). (text of announcement)

Johnson stated, “Mrs. Liuzzo went to Alabama to serve the struggle for justice. She was murdered by the enemies of justice, who for decades have used the rope and the gun and the tar and feathers to terrorize their neighbors.”

March 27, 1965 : a group of about 200 protesters, black and white, led by the Rev. James Orange of the SCLC marched to the Dallas County courthouse in Selma. The Rev. James Bevel told them, “[Viola Liuzzo] gave her life that freedom might be saved throughout this land.”

KKK Kills Activist Viola Liuzzo

Funeral services

March 29, 1965 : the NAACP sponsored a memorial service for Viola Liuzzo at the People’s Community Church in Detroit. Fifteen hundred people attended, among them, Rosa Parks.

March 30, 1965: funeral services were held for Viola Liuzzo. Her funeral was held at Immaculate Heart of Mary Catholic church in Detroit, with many prominent members of both the civil rights movement and government there to pay their respects. Included in this group were Martin Luther King, Jr.; NAACP executive director Roy Wilkins; Congress on Racial Equality national leader James Farmer; Michigan lieutenant governor William G. Milliken; Teamsters president Jimmy Hoffa; and United Auto Workers president Walter Reuther. At San Francisco’s Grace Episcopal Cathedral, Martin Luther King said of Liuzzo, “If physical death is the price some must pay to save us and our white brothers from eternal death of the spirit, then no sacrifice could be more redemptive.“

On April 1, a cross was burned in front of four Detroit homes, including the Liuzzo residence. (History Engine article)

April 3, 1965 : the mother of Collie Leory Wilkins told President Johnson that he has made it impossible for her son to have a fair trial.

KKK Kills Activist Viola Liuzzo

Indictments and trials

April 6, 1965 : a grand jury indicted Collie Wilkins, William Eaton, Eugene Thomas, and Gary Rowe.

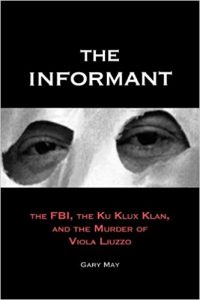

April 15, 1965 : all charges against Gary Rowe were dropped, and he was identified as a paid undercover FBI informant who would testify for the prosecution. [It will later be revealed that Rowe had participated in the beatings of Freedom Riders in Birmingham in 1961 and was suspected of involvement in the 1963 bombing of the Sixteenth Street Baptist Church.]

May 3, 1965 : the Wilkins trial began.

May 6, 1965 : during his final defense arguments Wilkens’s lawyer, Matt Murphy, made blatantly racist comments, including calling Liuzzo a “white nigger,” in order to sway the jury. The tactic was successful enough to result in a mistrial the following day (10-2 in favor of conviction)

May 10, 1965 : Collie Wilkins, William Eaton, and Eugene Thomas participated in a Ku Klux Klan parade. Collie Wilkins, free on bond after the mistrial, carried a Confederate flag. After the parade, the Imperial Wizard of the United Klans of America, Robert Shelton, asked the three men to stand. They received a standing ovation.

August 20, 1965 : Matt Murphy, the defendants’ lawyer in the Viola Liuzzo murder, died in an automobile accident after he fell asleep while driving and crashed into a gas tank truck. Segregationist and former mayor of Birmingham, Art Hanes, agree\ds to represent three accused killers.

October 19, 1965 : State Attorney General, Richmond M Flowers, interrupted the second Liuzzo trial and asked the Alabama Supreme Court to purge some jurists, a number of whom stated during jury selection that they believed white civil rights workers to be inferior to other whites. The request was denied.

October 20, 1965 : Roy Reed in the NY Times reported that, ”an all-white jury dominated by self-proclaimed white supremacists was chosen…for the retrial of Collie Leroy Wilkins, Jr, a Ku Klux Klansman charged with the murder of Viola Liuzzo.”

October 22, 1965 : the jury took less than two hours to acquit Collie Wilkins in Liuzzo’s slaying.

KKK Kills Activist Viola Liuzzo

Federal trial

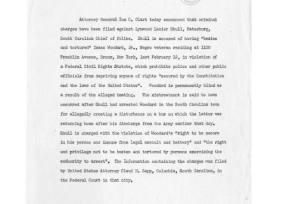

November 30, 1965 : Collie Wilkins (already acquitted in State Court), Eugene Thomas, and William Eaton faced trial on Federal charges that grew out of the killing of a Viola Liuzzo. They were charged with conspiracy under the 1871 Ku Klux Klan Act, a Reconstruction civil rights statute. The charges did not specifically refer to Liuzzo’s murder.

December 3, 1965 : an all-white jury found Collie Wilkins, Eugene Thomas, and William Eaton guilty. The three were sentenced to 10 years in prison.

January 15, 1966 : the Birmingham News newspaper published an ad offering Viola Liuzzo’s bullet-ridden car for sale. Asking $3,500, the ad read, “Do you need a crowd-getter? I have a 1963 Oldsmobile two-door in which Mrs. Viola Liuzzo was killed. Bullet holes and everything intact. Ideal to bring in crowds.”

April 27, 1967 : the US Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit upheld the conspiracy convictions of Thomas and Wilkins, Jr. William O Eaton, the third person, had died.

May 17, 1982 : the US Court of Appeals for the 11th Circuit ruled that Alabama could prosecute Gary Rowe, the FBI informer, in the 1965 slaying of Viola Liuzzo. The ruling affirmed an order by a lower court.

October 30, 1982 : a newly released report said the FBI covered up the violent activities of their informant, Gary Thomas Rowe Jr., but his lawyer said the Government knew it was not getting ”a Sunday school teacher” when it asked Mr. Rowe to infiltrate the Ku Klux Klan. (NYT article)

Rowe, who was a Klan informant from 1959 to 1965, was charged with murder in the 1965 killing of Viola Liuzzo, a civil rights worker, but a federal appeals court barred him from being brought to trial because of an earlier agreement giving him immunity.

The 1979 report was released publicly for the first time because the Justice Department lost a Freedom of Information suit filed by Playboy magazine. In the report department investigators said agents protected Mr. Rowe because the informant ”was simply too valuable to abandon.’

KKK Kills Activist Viola Liuzzo

Family must pay

April 2, 1983 : final arguments in the $2 million negligence suit against the FBI were made in Federal court by lawyers for the children of Viola Liuzzo, whose murder they attributed to a paid F.B.I. informer, Gary Rowe.

Viola Liuzzo’s children not only lost their suit against the Federal Government but were ordered to pay court costs of $79,800, in addition to legal fees that amounted to more than $60,000. They appealed the ruling which was reduced to a smaller amount.

The Liuzzo family’s court costs alone were estimated at $60,000, according to Jeffrey Long, one of their lawyers. Last week, Judge Joiner dismissed the family’s $2 million lawsuit against the Federal Government. The family maintained Gary Rowe, an informer for the FBI, either shot at Mrs. Liuzzo or could have prevented the shooting.

February 7, 1997 : from the NYT, “Last week, a Confederate battle flag was spray-painted on a monument in Hayneville, Ala., to Viola Liuzzo.”

KKK Kills Activist Viola Liuzzo

Legacy

April 10, 2015: Wayne State University posthumously awarded an honorary doctor of laws degree to Viola Liuzzo. Liuzzo’s family traveled from around the country to attend the ceremony and accept the award on her behalf.