Canned Heat Woodstock

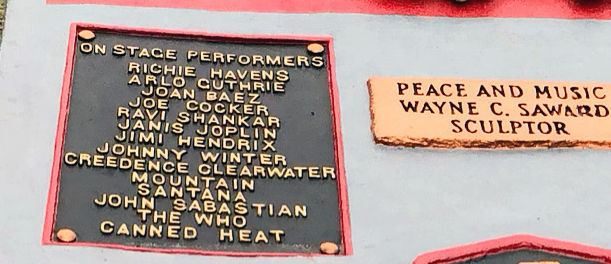

Canned Heat is on the Monument. Canned Heat is in the original movie release. Canned Heat is on the original soundtrack. They certainly deserved the triple.

It was around 7:30 PM when Chip Monck introduced Canned Heat. The 8 PM sunset ended a warm sunny day. The band would leave the stage about an hour and fifteen minutes later to cheers and applause.

Personnel:

- Alan “Blind Owl” Wilson: guitar, harmonica, vocals

- Bob “The Bear” Hite: vocals, harmonica

- Harvey “The Snake” Mandel: guitar

- Larry “The Mole” Taylor: bass

- Adolpho “Fito” de la Parra: drums

Setlist:

- I’m Her Man

- Going Up the Country

- A Change Is Gonna Come / Leaving This Town

- I Know My Baby

- Woodstock Boogie

- On the Road Again

Canned Heat Woodstock

I’m Her Man

I’m Her Man had appeared on their recently released Hallelujah album. Bob Hite wrote the song.

I found love sure is good to me

You know a man needs a woman though to keep him company

It feels good not to be alone

Oh so good not to be alone

I’m gonna make sure not to lose my happy home

Why i sure don’t know

Never gonna let her go

I said love is hard to understand

But it sure feels good to know that I’m her man

Why i sure don’t know

Never gonna let her go

Canned Heat Woodstock

Going Up the Country

Going Up the Country was on their Living the Blues album, their third and a double alum. Alan Wilson wrote the song.

Before starting it, Bob Hite, as many other performers had, commented on the whole scene, mentioned a personal issue, and introduced a new band member.

“You know, this is the most outrageous spectacle I’ve ever witnessed, ever. There’s only one thing I wish: I sure gotta’ pee. And there ain’t nowhere to go. We’re gonna get one out here on the guitar and do a little Going Up the Country and I’d also like to take this time to introduce you to our newest member. So now being official that Henry Vestine has left Canned Heat to form a group called Sun, we now have playing lead guitar Harvey Mandell…so everything’s together.”

I’m goin’ up the country, baby don’t you want to go?

I’m goin’ to some place, I’ve never been before

I’m goin’ I’m goin’ where the water tastes like wine

I’m goin’ where the water tastes like wine

We can jump in the water, stay drunk all the time

I’m gonna leave this city, got to get away

I’m gonna leave this city, got to get away

All this fussin’ and fightin’ man, you know I sure can’t stay

So baby pack your leavin’ trunk

You know we’ve got to leave today

Just exactly where we’re goin’ I cannot say

But we might even leave the U.S.A.

It’s a brand new game, that I want to play

‘Cause you got a home as long as I’ve got mine

Canned Heat Woodstock

A Change Is Gonna Come/Leaving This Town

There is no studio recording of “A Change Is Gonna Come.”

Bob Hite comments before, “Nothing like suckin’ on an orange. Kinda’ something neat about it. Reminds me of something…I do believe it’s a lovely evening for a boogie.”

During the song a young man from the audience climbs on stage but instead Hite allows him to stay. The kid grabs the pack of Marlboro cigarettes from Hite’s tee-shirt while they hug each other. They share a cigarette. It was a perfect Woodstock moment.

I said I believe…

Yeah ’bout a change is gonna come

I said I believe…

Yeah people the change… will surely come

We all have good peace of mind

Lord, I free they will surely surely come

Yeah, I believe in the morning

I believe I go ah back home

Well, I’ll tell I believe I’m gonna get up in the morning

Yeah, people ah people, I’m gonna go back home

Well, now I gotta find my little mama

You know I gotta have some gratitude beyond

Well…I’m standing sown at he crossroads,

My friend began to shout

Well, ah it’s all I’ve got my self a friend

Dolla I try… ah surely done

Well, when you’ve got yourself a good friend

You are the luckiest man on earth

I say you got yourself a good friend

Yeah now do know you’re the luckiest man on earth

‘Couse you’ve got love in your heart

Lord God’s good… all is winin’ call

Oh you gotta cool down

Well, I got to go an’ to when

When your troubles through to down mile

I said what you’re gonna do babe

Yeah time when your troubles show you to the line mile

Well, now you take youself a mouth full of sugar

You drink yourself a put of bottle turpentine

Well I believe in the morning yeah

‘Tou for it moun too tough

I said I believe in the big time

Lord roar the moan too tough

Well, I gotta find my little ride’

You know this time I’m goin’ back home

Well, I believe in this time on

Lord I wont be back for long

Well, I believe in this time …

Lord people I wont be back… go home

Well, now I got myself a grand of nothing

Child don’t you know it’s shocking I’ve been told

Canned Heat Woodstock

Rollin’ Blues

From the Woodstock Fandom site: “Rollin’ Blues”, originally written by John Lee Hooker, is a version of the Blues traditional “Rollin’ and Tumblin.'” Canned Heat recorded their version of “Rollin’ and Tumblin'” (which has hardly any similarities to “Rollin’ Blues”) on their first self-titled album. They also recorded and performed with Hooker, so it is not unusual that they played one of “his” songs at the festival.

Canned Heat Woodstock

Woodstock Boogie

Bob Hite again says the guitarists need some time to tune and that Sharon’s dad is looking for her backstage.

Alan Wilson says that new member Harvey continues the Canned Heat tradition of extensive re-tuning.

Again from the Woodstock Fandom site: The song “Woodstock Boogie” is basically an almost 30-minute jam, including a drum solo. On their album Boogie With Canned Heat the song is called “Fried Hockey Boogie.“

Canned Heat Woodstock

On the Road Again

Before their encore, Hite explains how difficult the previous two weeks had been, that they even thought that the band might end.

Chip Monck has pretty much lost his patience with the tower climbers. He asked Hite if he could interrupt to tell them, “Get the fuck down!”

“On the Road Again” first appeared on their second album, Boogie with Canned Heat, in January 1968; when an edited version was released as a single in April 1968, “On the Road Again” became Canned Heat’s first record chart hit and one of their best-known songs.

But I’m out on the road again

I’m on the road again

Well, I’m so tired of crying

But I’m out on the road again

I’m on the road again

Just to call my special friend

Out in the rain and snow

In the rain and snow

You know the first time I traveled

Out in the rain and snow

In the rain and snow

Not even no place to go

When I was quite young

When I was quite young

And my dear mother left me

When I was quite young

When I was quite young

Please don’t you cry no more

Don’t you cry no more

Take a hint from me, mama

Please don’t you cry no more

Don’t you cry no more

Down the road I’m going

That long old lonesome road

All by myself

But I ain’t going down

That long old lonesome road

All by myself

Gonna carry somebody else

Canned Heat Woodstock

The next act is Mountain.