American Lynching 3

1921 – 1933

Some rationalize American terrorism toward American Blacks by saying that poverty created the defensive urge in some poor whites, but Bob Dylan may have gotten closer to the truth when he wrote:

A South politician preaches to the poor white man

“You got more than the blacks, don’t complain

You’re better than them, you been born with white skin, ” they explain

And the Negro’s name

Is used, it is plain

For the politician’s gain

As he rises to fame

And the poor white remains

On the caboose of the train

But it ain’t him to blame

He’s only a pawn in their game.

Whatever the reason, the arc of justice, if it was bending toward justice, may have bent for some, but hardly for others–if at all.

As the lynchings continued the echoes of States Rights from the Civil War continued to thwart attempts by some to outlaw lynching.

Wade Thomas lynched

December 26, 1920: Wade Thomas was a native of Jonesboro County, Arkansas. On Christmas night 1920, Thomas was armed with a pistol and was playing a game of craps with his neighborhood black friends. Police officer Elmer “Snookums” Ragland raided the game, and shots were fired. Ragland was killed and Thomas was injured. Thomas escaped to the next county but was arrested there and brought back to Jonesboro County.

A coroner’s jury indicted Thomas for murder. Allegedly, Thomas confessed to killing Policeman Ragland, but claimed that he did not shoot until after he had been wounded twice. An angry mob stormed the court and told the judge to leave unless he wanted to witness the lynching. After Thomas was taken from his jail cell, a noose was draped around his neck and he was led to a telephone pole and hung. [Black Then article]

David Bunn killed running from lynch mob

October 11, 1921: Tarrant County Sheriff Carl Smith and Deputy Tom Snow shot David Bunn, a handcuffed Black man, as he fled to escape a white lynch mob. Four days before these officers shot Bunn, white mobs made three separate attempts to lynch him.

At 2:30 am on the morning of October 11, the officers handcuffed Mr. Bunn and loaded him into a police car. Mr. Bunn sat in terror as they drove, even saying to the officers that he feared being lynched. As they crossed the county line near Arlington, Sheriff Smith observed four automobiles approaching, and identified these vehicles as members of the lynch mob, saying to Mr. Bunn “I think that’s them…”

Fearing for his life, Mr. Bunn jumped, in handcuffs, from the police car. Rather than capture Mr. Bunn and return him to their car, Sheriff Smith and Deputy Snow shot and killed him as the mob approached. Four bullets were lodged in his body before Mr. Bunn fell into a roadside ditch and died. No one faced charges or accountability for Mr. Bunn’s murder. [EJI article]

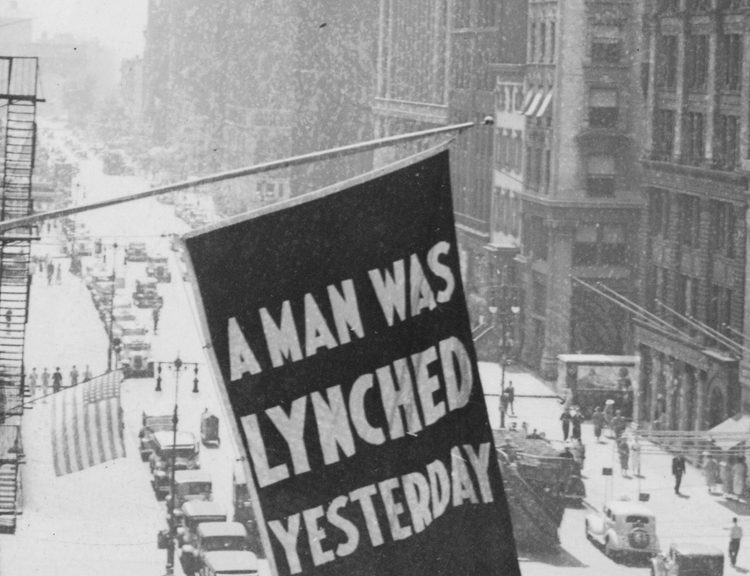

Dyer Anti-Lynching Bill

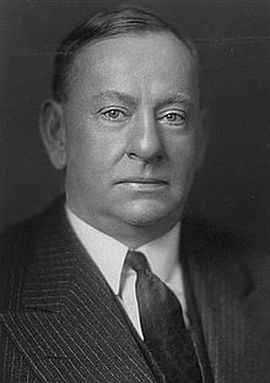

October 20, 1921: the House Judiciary Committee favorably reported Leonidas C. Dyer’s Anti-Lynching Bill which would impose heavy penalties on persons involved in mob action resulting in the taking of life.

Despite filibusters and ongoing southern Democratic obstruction, the House, controlled by a Republican majority, eventually passed the bill and sent it to the Senate where the like-minded southern Democrats were able to kill the bill.

See Dyer for an expanded chronology of the long sad story.

And lynching continued…

Robert Murtore, 15, lynched

November 30, 1921: a mob of white men in Ballinger, Texas, seized Robert Murtore, a 15-year-old Black boy, from the custody of law enforcement and, in broad daylight, shot him to death.

After a 9-year-old white girl alleged that she had been assaulted by an unknown Black boy, suspicion immediately fell on Robert, who worked in the same hotel as the white girl’s mother. He was arrested and held in the Ballinger jail, but word soon spread. On the morning of November 30, a white mob formed outside of the jail in an attempt to lynch Robert. Local law enforcement removed Robert from his cell for transport away from Ballinger; it is unclear whether this was to facilitate or block the lynching. [EJI article]

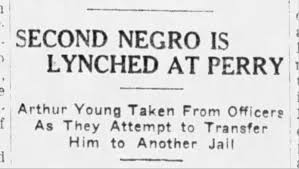

Arthur Young & Charles Wright lynched

December 12, 1922: Arthur Young and Charles Wright were accused of killing a local white school teacher. Though items found near the woman’s body belonged to a local white man, police were convinced the perpetrator had to be a black man, and quickly focused on Wright as a suspect. The deep racial hostility that permeated Southern society during this time period often served to focus suspicion on black communities after a crime was discovered, whether evidence supported that suspicion or not. This was especially true in cases of violent crime against white victims.

After several days of violent manhunts that terrorized the black community and left at least one black man dead, police arrested Charles Wright with a friend named Arthur Young. Before the men could be investigated or tried, a white mob seized Mr. Wright as they were being transported to jail and burned him alive.

Four days later, on December 12th, the lynch mob attacked again. As officers were moving Arthur Young to another jail, the mob seized him, riddled his body with bullets, and left his corpse hanging from a tree on the side of a highway in Perry, Florida. [EJI article]

American Lynching 3

Rosewood burned

January 1, 1923: in Sumner, Florida, Fannie Taylor, a sixteen-year-old married white woman, claimed she had been assaulted by Jesse Hunter, a black fugitive from a prison chain gang. There was no evidence against Hunter, but local white men launched a manhunt in Rosewood, a nearby town of about 200 black people. [Guardian report]

January 2, 1923: a mob of white men kidnapped, tortured, and lynched Sam Carter, a black craftsman from Rosewood, on suspicion that he had helped Jesse Hunter escape. White men continued to terrorize Rosewood searching for Hunter and black residents armed themselves in defense. [Black Past report]

January 4, 1923: hundreds of white men began the burning of Rosewood, Fla. Within three days, the entire African-American town had been burned to the ground. By the time the violence ended, six African Americans and two whites had died. No one was ever prosecuted. Survivors later recounted that Fannie Taylor had made false accusations against Jesse Hunter to conceal her extramarital affair with a white man. In 1994, the Florida Legislature voted to compensate victims and their families.

American Lynching 3

Moore v. Dempsey

February 19, 1923: in Moore v. Dempsey, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled 6-2 that mob-dominated trials violated the due process clause of the Fourteenth Amendment. In 1919, African-American sharecroppers had gathered in a church at Elaine, Ark., to discuss fairer prices for their products. White men fired into church, leading to three days of fighting and the killing of five white men and more than 100 black men, women and children. A white committee appointed by the governor concluded the black men planned to kill all the whites. More than 700 African-American men were arrested with 67 sent to prison and a dozen to Death Row. The Supreme Court reversed the cases on appeal, concluding the trial had been prejudiced by a white mob outside yelling that if the black men weren’t sentenced to death, the mob would lynch them. The court decision was a major victory for African Americans and the NAACP, which had represented the men. (PBS article)

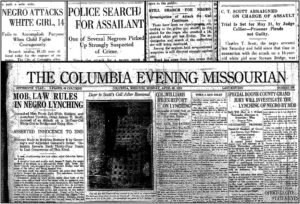

James T Scott lynched

April 29, 1923 a week after authorities arrested James T Scott for allegedly sexually assaulting the 14-year-old daughter of Missouri University German professor Hermann Almstedt, a mob forcibly removed the door from Scott’s cell in the Boone County Jail and marched him to a bridge near Stewart and Providence roads. A rope was placed around Scott’s neck, and he was hanged from the bridge before a hundreds of people without any opportunity to plead his case in court. [Missourian article] (ext BH, see June 21; next Lynching, see July 13 or see AL3 for expanded chronology of early 20th century lynching)

American Lynching 3

Murderer Acquitted

July 13, 1923: US House representative Leonidas Dyer of St Louis stated that he was not surprised at the acquittal of a George Barkwell at Columbia, Missouri on the charge of murder in connection with the lynching of James Scott, a Black. Dyer referred to statistics which, he said, showed that 3,824 lynchings had been recorded during the last thirty-five years and that in all those cases there had scarcely been a conviction. [H of R bio]

American Lynching 3

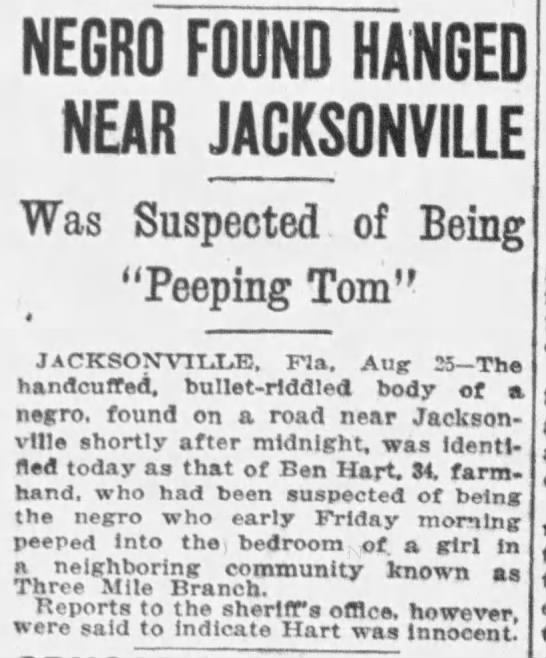

Ben Hart lynched

August 24, 1923: a 34-year-old black farmhand Ben Hart was killed based on suspicion that he was a “Peeping Tom” who had that morning peered into a young white girl’s bedroom window near Jacksonville, Florida. According to witnesses, approximately ten unmasked men came to Hart’s home around 9:30 p.m. claiming to be deputy sheriffs and informing Hart he was accused of looking into the girl’s window. Hart professed his innocence and readily agreed to go to the county jail with the men, but did not live to complete the journey.

Shortly after midnight the next day, Hart’s handcuffed and bullet-riddled body was found in a ditch about three miles from the city. Hart had been shot six times and witnesses reported seeing him earlier that night fleeing several white men on foot who were shooting at him as several more automobiles filled with white men followed.

Police investigating Hart’s murder soon determined he was innocent of the accusation against him; he was at his home 12 miles away when the alleged peeping incident occurred. [EJI story]

John Carter lynched

May 4, 1927: near Little Rock, Arkansas, two white women – Mrs. B.E. Stewart, age forty-five, and her daughter Glennie, seventeen – were driving a wagon on a rural road, heading toward Little Rock. According to their report a black man approached and assaulted them. Sheriff Mike Haynie organized a posse which found John Carter, a local black man.

Mob members took Carter to a telephone pole and hit him with a revolver. They told him to confess, and then to pray. Before he finished, someone put a rope around his neck and told him to climb on top of a car. When he couldn’t, he was pushed up. Someone drove the car out from under him and he swung in the air. A line of fifty men fired guns, striking Carter with more than two hundred bullets.

Despite a picture of the hanging body, with the crowd of 400+ visible in the background, none of the mob members admitted to being there. A report said Carter had been killed “by parties unknown in a mob.”3

The mob took Carter’s body to Little Rock to burn it. When they got to the city, they tied him to the car’s bumper and dragged him through the city for an hour. The mob eventually stopped at Ninth and Broadway, the center of the black business district. They poured gasoline and kerosene over Carter’s body. They piled on boxes, tree limbs, and pews from the nearby Bethel A.M.E. Church, and lit the fire. More white people hurried to the area. By that point the crowd was about seven thousand men, women, and children watching.

No one was ever charged or prosecuted for lynching John Carter. [Black Then article; ABHM article]

American Lynching 3

Lynch law for Blacks only

July 15, 1930: Senator Coleman L. Blease‘s advocated a lynch law for Blacks (only) guilty of criminally assaulting white women. “Whenever the Constitution comes between me and the virtue of the white women of South Carolina, I say ‘To hell with the Constitution.’ “

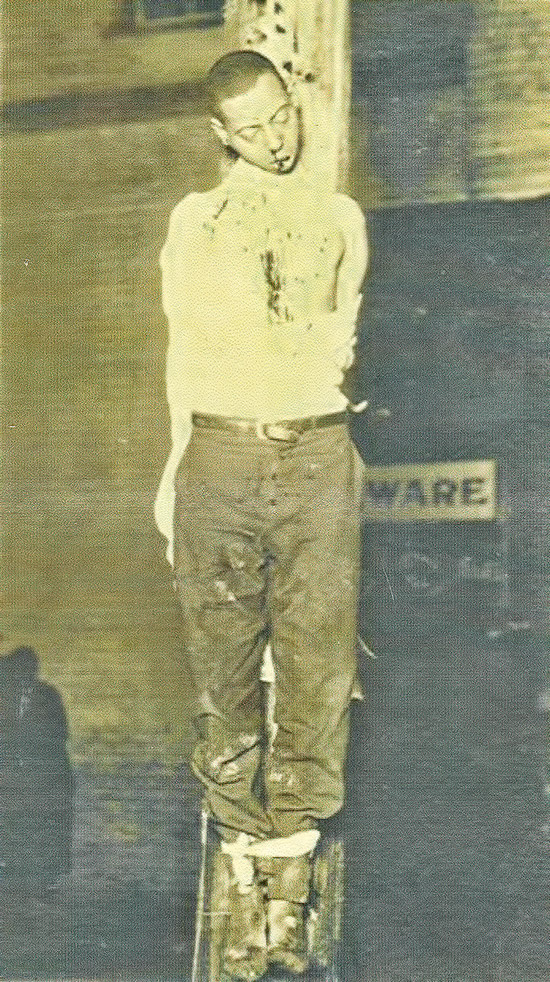

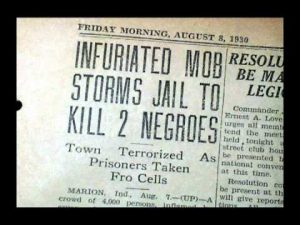

Thomas Shipp and Abram Smith lynched

August 7, 1930: a white mob lynched Thomas Shipp and Abram Smith in Marion, Indiana. The two young black men, 18 and 19 years old respectively, had been arrested that afternoon. They were accused of attacking a young white couple, beating and fatally shooting the man, and attempting to assault the woman. Once the men were detained, word of the charges spread and a growing mob of angry white residents gathered outside the county jail.

Around 9:30 p.m., the mob attempted to rush the jail and was repelled by tear gas. An hour later, they successfully barreled past the sheriff and three deputies, grabbed Shipp and Smith from their cells as they prayed, and dragged them into the street. By then numbering between 5000 and 10,000 people (half the white population of Grant County) the mob beat, tortured, and hung both men from trees in the courthouse yard, brutally executing them without benefit of trial or legal proof of guilt. As the men’s bodies hung, members of the mob re-entered the jail and grabbed 16-year-old James Cameron, another youth being held for the crime. The mob beat Cameron severely and were preparing to hang him alongside the others when a member of the crowd intervened and insisted he was innocent. Cameron was released and the mob later dispersed.

Enraged by the lynching, the NAACP traveled to Marion to investigate, and later provided United States Attorney General James Ogden with the names of 27 people believed to have participated. Though the lynching and its spectators were photographed, local residents claimed not to recognize anyone pictured and no one was charged or tried in connection with the killings. A photograph of Shipp’s and Smith’s battered corpses hanging lifeless from a tree, with white spectators proudly standing below, remains one of the most iconic lynching photographs. After seeing the photo in 1937, New York schoolteacher Abe Meeropol was inspired to write “Strange Fruit,” a haunting poem about lynching that later became a famous song recorded by Billie Holiday. [Black Past article]

American Lynching 3

1930

Henry Argo Lynched

May 31, 1930: Henry Argo, a 19-year-old Black man, was lynched after a mob of over 1,000 white men and boys as young as 12 stormed the Grady County jail in Chickasha, Oklahoma. He was shot in the head and stabbed by members of the mob, despite the presence of the National Guard who were ordered to protect him.

Mr. Argo had been accused of assaulting a white woman.

The mob of white people was led by a white man named George Skinner, who had accused Mr. Argo of assaulting his wife. The mob assembled late the night before, on May 30, after Mr. Argo had been arrested and taken into custody. They attempted to use sledgehammers and battering rams to break into the jail and kill Mr. Argo. The National Guard was then deployed to protect Mr. Argo, but they failed. [EJI article]

Jessie Daniel AmesLyn

November 20, 1930: The Association of Southern Women for the Prevention of Lynching founded in Atlanta, Georgia by Jessie Daniel Ames, a white Texas-born woman active in suffrage and interracial reform movements. The ASWPL was comprised of middle and upper-class white women who objected to the lynching of African Americans.

Anti-Lynching Congress

November 25, 1930: a delegation from the Anti-Lynching Congress, which was meeting in Washington, D.C., delivered a protest to President Herbert Hoover, demanding that he take action to end the lynching of African-Americans. The group was led by Maurice W. Spencer, president of the National Equal Rights League and Race Congress. President Hoover did not respond.

Herbert Hoover was basically sympathetic to the needs of African-Americans in American society, but was not willing to expend any political capital on civil rights. He was very upset, for example, when Southern bigots protested when First Lady Lou Henry Hoover invited the wife of African-American Congressman Oscar DePriest to the White House for tea (along with all the other Congressional wives), on June 12, 1929. He responded by inviting Robert Moton, President of Tuskegee University, to the White House in a symbolic gesture.

American Lynching 3

1931

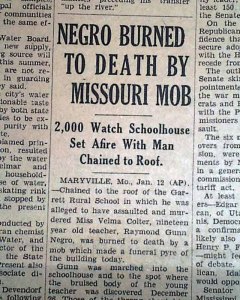

Raymond Gunn lynched

January 12, 1931: authorities arrested Raymond Gunn, an African American man, after he was accused of killing a white schoolteacher.

Following his arrest, police took Gunn to jail in a neighboring county due to threats of lynching. Lynch mobs still formed and attempted to seize Gunn from jail, so officials transported him to another prison with reinforcement from firemen and a tank company of the Missouri National Guard.

On January 12, the morning of Gunn’s arraignment, a mob of about two thousand white men, women, and children gathered outside the courthouse. Despite the previous attacks, the local sheriff did not request assistance from the National Guard. With little resistance from local law enforcement, and sixty members of the National Guard at ease in an armory one block from the courthouse, Mr. Gunn was seized by the mob and burned on the roof of the schoolhouse. [EJI article]

Residents flee

January 14, 1931: black residents of Maryville, Missouri fled the town after the lynching of Raymond Gunn on January 12. More than 20 percent of Maryville’s black population fled the town in fear. Despite investigations initiated by state officials, no one was ever arrested or convicted of any crime related to the lynching of Raymond Gunn. [EJI article]

American Lynching 3

1933

Reuben Micou lynched

April 2, 1933: a mob of white men broke into the Winston County jail in Louisville, Mississippi to lynch a 65-year-old black man named Reuben Micou. Micou had been arrested after he was accused of getting into an altercation with a prominent local white man.

Micou’s body was found in a nearby churchyard, riddled with bullets and bearing injuries suggesting that Micou had been whipped. Seventeen white men were indicted and arrested for participating in the lynching, but in July 1933 the cases against the seventeen men were “indefinitely postponed.” No one was ever tried or convicted for Micou’s murder. [EJI story]

George Armwood lynched

October 18, 1933: a mob of at least 2000 white residents of Princess Anne, Maryland beat, hanged, dragged, and burned George Armwood to death. Armwood, reportedly known to be “feeble-minded,” had been accused of assaulting an 80-year-old woman who was also the mother of a local white policeman. Shortly after being arrested, Armwood was dragged out of the jail and an 18-year-old boy immediately cut off his ear with a butcher knife. The growing mob then beat George Armwood nearly to death and dragged him to a tree, where he was hanged. Afterward, the mob cut down his corpse, dragged it through the streets, hanged it again, and then staged a public burning. The New Journal and Guide reported that “[m]en, women and children, participated in the savage orgy.”

Armwood’s lynching sparked a national outcry and calls for prosecution of the lynchers, yet investigations at the county, state, and federal levels faced obstacles and delays. Inquiries following the lynching were marked by residents’ refusal to identify participants as well as mockery and intimidation of black witnesses. The American Civil Liberties Union, frustrated with the silence, began offering a $1000 reward to people willing to name leaders of the mob.

Even when finally presented with identifying evidence, the county prosecutor refused to act. When the Maryland Attorney General ordered troops to arrest eight named participants, white residents who supported the accused lynchers waged riots of protest. Four white men were ultimately tried for the lynching of George Armwood, and acquitted by all-white juries. [EJI article]

For previous and subsequent chronologies, see…

- Never Forget American Lynching

- American Lynching 2

- American Lynching 4

- also see Dyer Anti-Lynching Bill