Early 20th Century News Music

I once did a project on what is usually called protest music of the 1960s. What I quickly discovered was that protest music is not limited to the 1960s (as much as we Boomers would like to think it is since we “invented” it–insert funny face emoji).

I once did a project on what is usually called protest music of the 1960s. What I quickly discovered was that protest music is not limited to the 1960s (as much as we Boomers would like to think it is since we “invented” it–insert funny face emoji).

Eventually, I also realized that protest music comes in a variety of approaches. The 1960s protest music was typically obvious in its approach: Masters of War, I Ain’t a’Marchin’ Anymore, Eve of Destruction, et cetera.

Earlier versions were equally powerful in their own way and I eventually settled on the term “News Music” to describe the genre. I’m not sure whether it is be best description, but one of the things that the songs and songwriters seemed to share was a reaction to current conditions. In other words, they were reacting to a current situation far more often than a past occurrence. Thus “News Music.”

Here are some examples of what are early 20th century news music:

Early 20th Century News Music

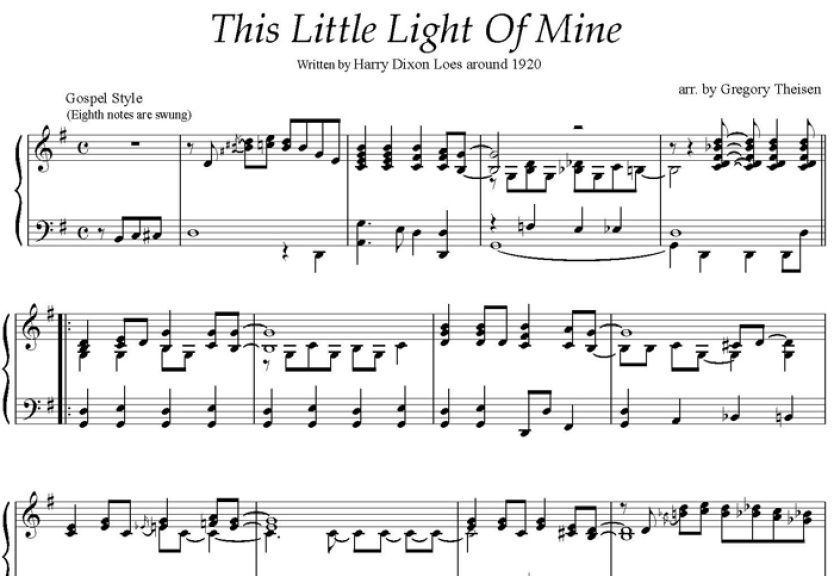

Harry Dixon

Around 1920: Harry Dixon (1895 – 1965) wrote “This Little Light of Mine” as a gospel song. It became a common one sung during the civil rights gathering of the 1950s and 1960s. It continues to be a song of hope today. (BH, see January 4, 1920)

Early 20th Century News Music

Fats Waller

In 1929: composed by Fats Waller with lyrics by Harry Brooks and Andy Razaf, Edith Wilson (1896 – 1981) sang “(What Did I Do to Be So) Black and Blue.”. It is a protest song that did not speak of how something should change so much as it spoke of what life was like for those who suffered inequities.

Early 20th Century News Music

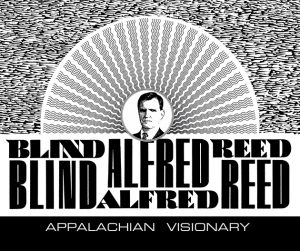

Blind Alfred Reed

In 1929: Blind Alfred Reed (1880 – 1956) wrote “How Can A Poor Man Stand Such Times and Live?” The song describes life during the Great Depression.

Early 20th Century News Music

Florence Reece

In 1931: Florence Reece (1900-1986) “was a writer and social activist whose song ‘Which Side Are You On?’ became an anthem for the labor movement. Borrowing from the melody of the old hymn ”Lay the Lily Low,” Mrs. Reece wrote the union song…to describe the plight of mine workers who were organizing a strike in Harlan County, Ky. Mrs. Reece’s husband, Sam, who died in 1978, was one of those workers. Pete Seeger, the folk singer, recorded the song in 1941. It has since been used worldwide by groups espousing labor and social issues.” — New York Times Obituaries, August 6, 1986. (Labor, see March 3; Feminism, see Dec 10)

Early 20th Century News Music

Brother Can You Spare a Dime

In 1931: “Brother Can You Spare a Dime” by lyricist E. Y. “Yip” Harburg and composer Jay Gorney., the song asked why the men who built the nation – built the railroads, built the skyscrapers – who fought in the war (World War I), who tilled the earth, who did what their nation asked of them should, now that the work is done and their labor no longer necessary, find themselves abandoned, in bread lines.

Harburg believed that “songs are an anodyne against tyranny and terror and that the artist has historically always been on the side of humanity.” As a committed socialist, he spent three years in Uruguay to avoid being involved in WWI, as he felt that capitalism was responsible for the destruction of the human spirit, and he refused to fight its wars. A longtime friend of Ira Gershwin, Harburg started writing lyrics after he lost his business in the Crash of 1929.

Early 20th Century News Music

Jimmie Rodgers

In 1932: Jimmie Rodgers (1897 – 1933) was born in Meridian, Mississippi worked on the railroad as his father did but at the age of 27 contracted tuberculosis and had to quit. He loved entertaining and eventually found a job singing on WWNC radio, Asheville, North Carolina (April 18, 1927). Later he began recording his songs. The tuberculosis worsened and he died in 1933 while recording songs in New York. In 1932 he recorded “Hobo’s Meditation.”

Early 20th Century News Music

Lead Belly

In 1938: Lead Belly (born Huddie William Ledbetter) (1888 – 1949) sang about his visit to Washington, DC with his wife and their treatment while in the nation’s capitol in his song, “Bourgeois Blues.” (BH, see Nov 22)

Early 20th Century News Music

Woody Guthrie

“Do Re Mi”

In 1939: During the Great Depression, Woody Guthrie (1912-1967) wrote many songs reflecting the plight of farmers and migrant workers caught between the Dust Bowl drought and farm foreclosure. One of the best known of these songs is his “Do Re Mi.”

Tom Joad

In 1940: Woody Guthrie wrote Tom Joad, a song whose character is based on John Steinbeck’s character in The Grapes of Wrath. After hearing it, Steinbeck reportedly said, “ That f****** little b******! In 17 verses he got the entire story of a thing that took me two years to write.”

Early 20th Century News Music

This Land Is Your Land

February 23, 1940: Woody Guthrie wrote the lyrics to ‘This Land Is Your Land‘ in his room at the Hanover House Hotel in New York City. He would not record the song until 1944. It was a musical response to Irving Berlin’s “God Bless America”: “We can’t just bless America, we’ve got to change it.”

Early 20th Century News Music

In 1941: the Almanac Singers (Millard Lampell, Lee Hays, Pete Seeger, and Woody Guthrie) released Talking Union, an album containing pro-union songs. One was Florence Reece’s Which Side Are You On? Another was I Don’t Want Your Millions, Mister (written by Jim Garland), a song that was used by Occupy Wall Street protestors.

During World War II, Guthrie printed the words, “This Machine Kills Fascists” on his guitar as a sign of his support of the war cause. Shortly afterwards, Pete Seeger printed the words, “This Machine Surrounds hate and Forces It to Surrender” on his banjo. Current guitarist, Tom Morello, often uses a guitar with the words, “Arm the Homeless” printed on it.