Japanese Internment Camps

On December 8, 1941, the day after Japanese forces attacked Pearl Harbor, US Attorney-General Biddle called for tolerance in dealings with Japanese here “of unquestioned loyalty,” but in less than a month, many Americans felt the need to physically isolate those they perceived a danger. (Main Line Today article on Biddle)

Japanese Internment Camps

January 1942

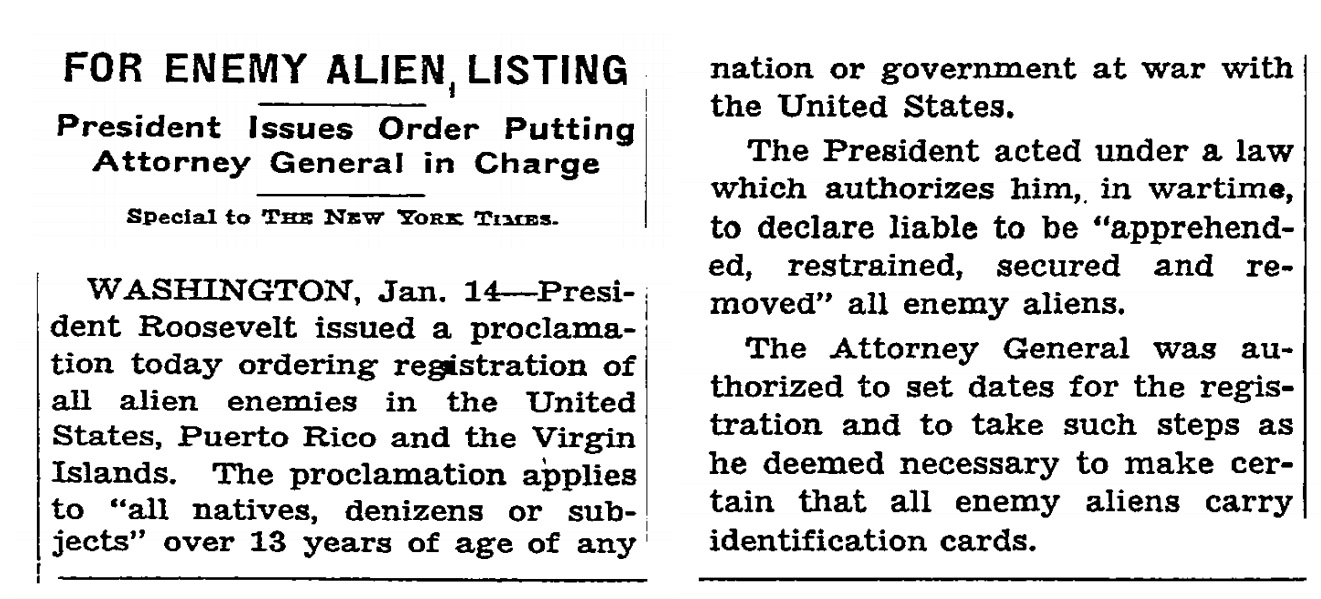

January 14, 1942: President Franklin D. Roosevelt issued Presidential Proclamation No. 2537, requiring aliens from World War II-enemy countries–Italy, Germany and Japan–to register with the United States Department of Justice. Registered persons were then issued a Certificate of Identification for Aliens of Enemy Nationality.

January 22, 1942 : Congressman Ford (Calif.) urged total evacuation of all persons of Japanese ancestry.

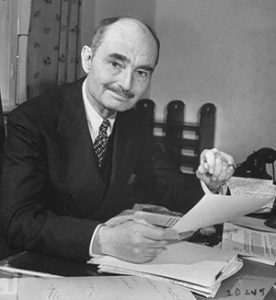

January 31, 1942: Caleb Foote, a pacifist and West Coast staff member for the Fellowship of Reconciliation (FOR), denounced the developing plans to evacuate and intern all Japanese-Americans on the West Coast as “nothing could be more Hitlerian.”

Foote’s comment was one of the few during the war to draw the obvious comparison between the government’s plan and Adolph Hitler’s Nazi policies: stereotyping an entire group on the basis of their race, assuming that all members of the group posed a threat, and confining them to concentration camps without a trace of due process.

Foote went on to a distinguished civil liberties career. As a pacifist, he refused to cooperate with the draft, and was convicted and sentenced to prison. He later became a law professor and, in the 1950s, wrote path-breaking articles on how the money bail system in America discriminated against the poor. His articles stirred interest in the problems with the American bail system and helped pave the way for the historic 1966 Bail Reform Act, signed on June 22, 1966. (ASX article on Foote)

Japanese Internment Camps

February 1942

February 13, 1942: the Pacific Coast Congressional group recommends evacuation.

February 19, 1942: President Franklin D. Roosevelt signed and issued Executive Order 9066 authorizing the Secretary of War to prescribe certain areas as military zones.

Eventually, EO 9066 cleared the way for the relocation of Japanese Americans to internment camps.

During the course of World War II, 10 Americans were convicted of spying for Japan. Not one was of Japanese ancestry.

Japanese Internment Camps

March 1942

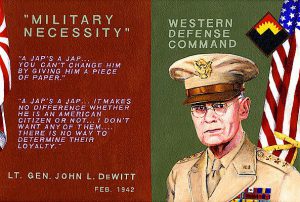

March 2, 1942: General John L. DeWitt ordered evacuation from most of California, western Oregon and Washington, and southern Arizona. (NYT abstract)

March 2, 1942: General John L. DeWitt ordered evacuation from most of California, western Oregon and Washington, and southern Arizona. (NYT abstract)

March 18, 1942: the War Relocation Authority was created to “Take all people of Japanese descent into custody, surround them with troops, prevent them from buying land, and return them to their former homes at the close of the war.”

While roughly 2,000 people of German and Italian ancestry were interned during this period, 120,000 men, women, and children of Japanese ancestry were rounded up on the West Coast.

Three categories of internees were created: Nisei (native U.S. citizens of Japanese immigrant parents), Issei (Japanese immigrants), and Kibei (native U.S. citizens educated largely in Japan). The internees were transported to one of 10 relocation centers in California, Utah, Arkansas, Arizona, Idaho, Colorado, and Wyoming.

March 24, 1942: more than 600 Japanese aliens and Japanese-Americans from the Pacific Coast assembled at Pasadena’s Rose Bowl under military orders to evacuate to an internment camp in Manzanar, Calif.

The New York Times referred to the arrivals as “pioneers,” said that “all” the evacuees “had been vastly impressed” with the “courteous treatment” they had received so far, and that “good humor” prevailed. (NYT article)

March 29, 1942: ”Voluntary evacuation” of people of Japanese ancestry from Pacific Coast area prohibited. Before this date 10,231 moved out of restricted area on their own initiative after Army and newspapers requested this.

Japanese Internment Camps

Long-term policy

April 7, 1942: at a conference in Salt Lake City, Utah officials of the War Relocation Authority and the governors and other officials of nine western and mountain states debated what to do with the Japanese Americans, who were being forcibly evacuated from the West Coast. President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s Executive Order 9066 (February 19, 1942) mentioned only evacuation and said nothing about what would happen to the evacuees. State officials strongly objected to having evacuees in their states. As a result, the decision was made to create a network of Relocation Centers, which have been more properly characterized as concentration camps. (A New York Times article on the conference referred to the “voluntary movement” of Japanese-Americans.)

June 5, 1942: first evacuation completed. Subsequently the remaining parts of California were evacuated, this being completed August 7, 1942.

Japanese Internment Camps

Court challenges

September 1, 1942: in the first specific ruling on the constitutionality of actions by President Roosevelt, by Congress, and by Gen. John L. DeWitt in connection with evacuation of Japanese on the Pacific Coast, federal Judge Martin I Welsh of District Court of Northern California held that the Army was within its rights in evacuating, and in keeping in protective custody, all American-born Japanese as well as Japanese nationals.

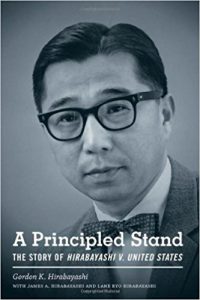

June 21, 1943: authorities had convicted Gordon Hirabayashi of violating the curfew affecting Japanese-Americans in Seattle in 1942. In Hirabayashi v. United States — the first Japanese-American case to reach the Supreme Court — the Court upheld the curfew.

June 21, 1943: authorities had convicted Gordon Hirabayashi of violating the curfew affecting Japanese-Americans in Seattle in 1942. In Hirabayashi v. United States — the first Japanese-American case to reach the Supreme Court — the Court upheld the curfew.

Japanese Internment Camps

Life in Camps

October 15, 1943: at the internment camp in California – which held over 18,000 Japanese Americans during World War II – a truck carrying agricultural workers tips over, resulting in the death of an internee. Ten days later, the agricultural workers went on strike; the internment camp director fired all of the workers and brought in strikebreakers from other internment camps. After several outbreaks of violence, martial law was declared and 250 internees were arrested and incarcerated in a newly constructed prison within the prison.

War winds down

December 17, 1944: Major General Henry C. Pratt issued Public Proclamation No. 21, declaring that, effective January 2, 1945, Japanese American “evacuees” from the West Coast could return to their homes.

Fred Korematsu challenges internment

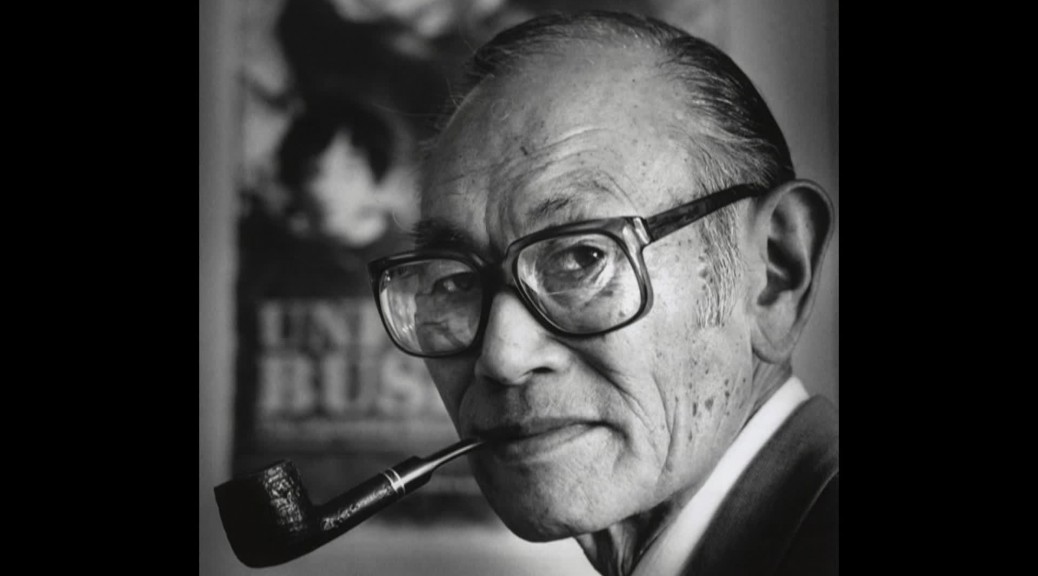

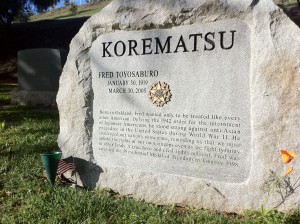

December 18, 1944: brought by Japanese-American Fred Korematsu regarding the Japanese internment, the Supreme Court sided with the government in Korematsu v. United States ruling that the exclusion order was constitutional. Korematsu (see for more)

Aftermath

November 21, 1945: Manzanar, one of the Relocation Centers (usually referred to as concentration camps) in the evacuation and internment of the Japanese-American during World War II, was officially closed on this day.

Many historians regard the evacuation and internment of the Japanese-Americans as the greatest civil liberties tragedy in American history. The government’s program was officially ended on December 17, 1944, but Manzanar did not close until this day, almost a year later.

The site was designated a National Historic Site, on March 3, 1992, and is now managed by the National Park Service.

February 2, 1948: President Harry Truman delivered a special message to Congress on civil rights, with a set of legislative proposals. His proposals were based in large part on the report of his Civil Rights Committee, “To Secure These Rights,” [released on October 29, 1947].

This was the first-ever, comprehensive presidential message on civil rights. Truman recommended the establishment of a permanent Commission on Civil Rights; federal protection against lynching; protection of the right to vote; settling claims of Japanese-Americans who had been relocated after the attack on Pearl Harbor; statehood for Alaska and Hawaii; suffrage and self-government for the District of Columbia; and “prohibiting discrimination in interstate transportation facilities.”

Japanese Internment Camps

Norman Minetta

January 3, 1975: Norman Minetta, who had been interned as a child as part of the Japanese-American evacuation and internment during World War II, took his seat in the House of Representatives. Minetta represented the San Jose, California area, and served in the House until 1995. He later served as Secretary of Commerce under President Bill Clinton (2000–2001) and then Secretary of Transportation under President George W. Bush (2001–2006). (HuffPost article on Minetta)

January 3, 1975: Norman Minetta, who had been interned as a child as part of the Japanese-American evacuation and internment during World War II, took his seat in the House of Representatives. Minetta represented the San Jose, California area, and served in the House until 1995. He later served as Secretary of Commerce under President Bill Clinton (2000–2001) and then Secretary of Transportation under President George W. Bush (2001–2006). (HuffPost article on Minetta)

Symbolic apology

February 19, 1976: in a largely symbolic act in the Bicentennial year, President Gerald Ford on this day issued Proclamation 4417, officially rescinding President Franklin Roosevelt’s Executive Order 9066, authorizing the evacuation of Japanese-Americans from the West Coast. President Ford rescinded Roosevelt’s order on the same day Roosevelt had acted, thirty-four years later. (See February 19, 1942.) Although a symbolic act, President Ford’s order was an important statement, nonetheless.

Michi Weglyn’s Years of Infamy

May 3, 1976: Michi Weglyn’s Years of Infamy published. It became one of the most widely read and cited books on the internment.

Japanese Internment Camps

Further Government review

July 31, 1980: President Carter signs the Commission on Wartime Relocation and Internment of Civilians Act which created a group of people appointed by the U.S. Congress to conduct an official governmental study of Executive Order 9066, related wartime orders and their impact on Japanese Americans in the West and Alaska Natives in the Pribilof Islands.

February 22, 1983: The Report of the Commission of Wartime Relocation and Internment of Civilians (CWRIC), entitled Personal Justice Denied, concluded that the exclusion, expulsion, and incarceration of Japanese-Americans were not justified by military necessity, and the decisions to do so were based on race prejudice, war hysteria, and a failure of political leadership.

Japanese Internment Camps

Fred Korematsu reviewed

November 10, 1983: the 1944 challenge that Fred Korematsu brought regarding the Japanese internment and that the Supreme Court sided with the government in Korematsu v. United States ruling that the exclusion order was constitutional, in response to a petition of error coram nobis (“error before us”) by Fred Korematsu, the San Francisco Federal District Court reversed Korematsu’s 1942 conviction and rules that the internment was not justified.

Civil Liberties Act of 1988

August 10, 1988: Civil Liberties Act of 1988, signed by President Reagan and passed by Congress, provided for a Presidential apology and appropriates $1.25 billion for reparations of $20,000 to most internees, evacuees, and others of Japanese ancestry who lost liberty or property because of discriminatory wartime actions by the government. Civil Liberties Public Education Fund created to help teach the public about the internment period.

August 10, 1988: Civil Liberties Act of 1988, signed by President Reagan and passed by Congress, provided for a Presidential apology and appropriates $1.25 billion for reparations of $20,000 to most internees, evacuees, and others of Japanese ancestry who lost liberty or property because of discriminatory wartime actions by the government. Civil Liberties Public Education Fund created to help teach the public about the internment period.

Japanese Internment Camps

Redress payments

October 9, 1990: first Japanese internment redress payments issued at a Washington, D.C. ceremony. Reverend Mamoru Eto, 107 years old, was the first to receive his check.

US Concentration Camps as historic sites

March 3, 1992: Manzanar was one of ten Relocation Centers.

It had held just over 10,000 detainees. On this day, Manzanar became a National Historic Site, managed by the National Park Service. Later, two other Relocation Centers also would also have national landmark status: Tule Lake (designated on February 17, 2006) and Heart Mountain (designated on September 20, 2006).

Additional funding

May 21, 1999: Congress passed legislation for additional funding to pay remaining eligible claimants who had filed timely claims under the Civil Liberties Act of 1988 and the Mochizuki settlement agreement.

Japanese Internment Camps

National Memorial

October 22, 1999: groundbreaking on construction of a national memorial to both Japanese-American soldiers and those sent to internment camps took place in Washington, D.C. with President Clinton in attendance.

Japanese Internment Camps

21st Century

February 2. 2000: the White House announced its proposal for a new, $4.8 million initiative to help acquire and preserve several WWII concentration camp sites throughout the country.

December 21, 2006: President George W. Bush signed into law a bill that authorized up to $38 million for the preservation and interpretation of confinement sites where Japanese Americans were detained during World War II. The law directed the National Park Service to administer this grant program, once funds were available.

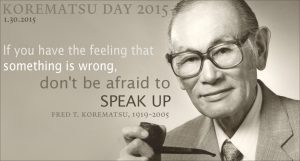

Fred Korematsu Day

January 30, 2011: the first Fred Korematsu Day was celebrated to commemorate Korematsu, who was evacuated and interned during World War II along with about 120,000 other Japanese-Americans following the attack on Pearl Harbor. California established the day in September 2010.

January 30, 2011: the first Fred Korematsu Day was celebrated to commemorate Korematsu, who was evacuated and interned during World War II along with about 120,000 other Japanese-Americans following the attack on Pearl Harbor. California established the day in September 2010.

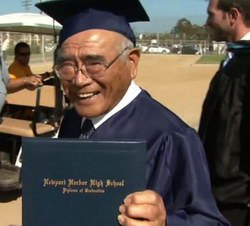

Don Miyada

June 19, 2014: Don Miyada, 89, joined Newport (CA) Harbor High School’s 2014 graduating class on stage and received a standing ovation when he was hailed as an inaugural member of the school’s hall of fame. Miyada missed his 1942 graduation because he was locked in an internment camp for Japanese-Americans

Miyada was 17 when he was sent with his family and more than 17,000 other detainees to a patch of desert land near Poston, Arizona shortly after the Japanese bombed Pearl Harbor during World War II. A teacher later sent him a letter expressing shock that he couldn’t finish high school and included a diploma — but Miyada always regretted that he missed the celebration. (LA Times article)

Japanese Internment Camps

Current events

Walmart

November 11, 2017: Walmart removed the posters it was selling on its website of Japanese-American incarceration during World War II. Walmart took them down after author Jamie Ford tweeted the company asking why it was selling the posters and noting the offensive description of the products.

One particular poster featured a child waiting to be taken to an incarceration camp, and was advertised as “the perfect wall art for any home, bedroom, playroom, classroom, dorm room or office workspace.”

Wallmart said, ““We are very sorry such a sensitive topic was handled in such an insensitive way. The description used for these products was beyond tone-deaf, and unfortunately it wasn’t caught by us or the marketplace seller who listed these products on our site. When we were contacted about these over the weekend, we quickly removed the items from our Marketplace. We apologize this wasn’t caught sooner.”

Trump v Hawaii

June 26, 2018: In Trump v Hawaii, the US Supreme Court upheld President Trump’s ban on travel from several predominantly Muslim countries, but in doing so Chief Justice Roberts’s comments officially overruled Korematsu—which upheld the exclusion of persons of Japanese ancestry, including US citizens, from their west coast homes during World War II.

Although Korematsu had been widely condemned, the Court had never formally overruled it. Quoting Justice Jackson’s dissent, Chief Justice Roberts took “the opportunity to make express what is already obvious: Korematsu was gravely wrong the day it was decided, has been overruled in the court of history, and—to be clear—’has no place in law under the Constitution.’ ”

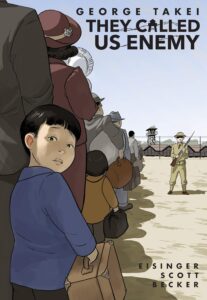

They Called Us Enemy

In 2019, Top Shelf Productions published the graphic novel They Call Us Enemy by George Takei, Justine Eisnger, and Steven Scott. It is the first-hand account of Takei’s experience in an internment camp.

In 2019, Top Shelf Productions published the graphic novel They Call Us Enemy by George Takei, Justine Eisnger, and Steven Scott. It is the first-hand account of Takei’s experience in an internment camp.

California Assembly apologized

February 20, 2020: Hawaii News Now reported that the California Assembly apologized for discriminating against Japanese Americans and helping the U.S. government send them to internment camps during World War II.

The Assembly unanimously passed the resolution as several former internees and their families looked on. After the votes, lawmakers gathered at the entrance of the chamber to hug and shake hands with victims, including 96-year-old Kiyo Sato.

The California resolution said anti-Japanese sentiment began in California as early as 1913, when the state passed the Alien Land Law, targeting Japanese farmers who were perceived as a threat by some in the massive agricultural industry. Seven years later, the state barred anyone with Japanese ancestry from buying farmland.

Internment artwork defaced

February 26, 2020: Seattle artist Erin Shigaki had created the art installation “Never Again Is Now,” which included an 11-foot-tall mural of two children photographed at a California incarceration camp.

On this date, the Seattle Times reported that Bellevue College had apologized after Gayle Colston Barge, vice president of institutional advancement altered a mural of two Japanese American children in a World War II incarceration camp by whiting out a reference to anti-Japanese agitation by Eastside businessman Miller Freeman and others in the artist’s accompanying description.

Bellevue President Jerry Weber’s letter of apology read, “It was a mistake to alter the artist’s work. Removing the reference gave the impression that the administrator was attempting to remove or rewrite history, a history that directly impacts many today … Editing artistic works changes the message and meaning of the work.”

United States Japanese Internment Camps

The Ireichō

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/ae/d3/aed370cd-41f6-4bb2-803f-b3fca6678fdf/ireicho_and_sotoba_horizontal_crop_in_room.jpeg)

November 18, 2022: a Smithsonian Magazine article reported that Duncan Ryuken Williams, director of the University of Southern California’s Shinso Ito Center for Japanese Religions and Culture had finally collected the names of every Japanese-American the US Government had interred.

For three years, he worked with a dozen researchers and some 100 volunteers, compiling files from 75 incarceration camps across the country.

The Ireichō is 1,000 pages long and contains 125,284 names.