Declan O’Rourke Indian Meal

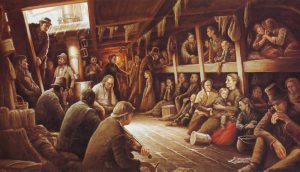

It is easy to think that during the Great Irish Famine–caused mainly by the potato blight–that there was no other food available to the starving.

Not the case.

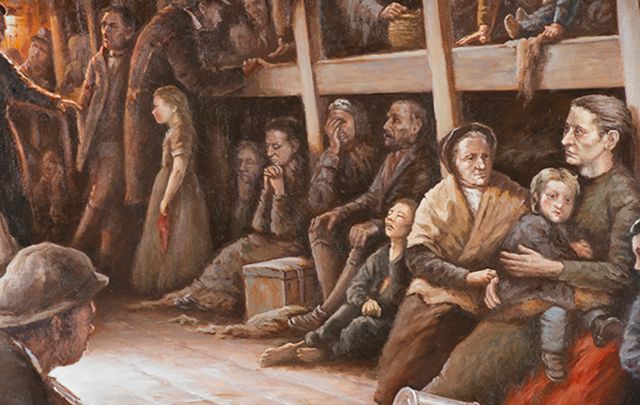

As noted in the previous Chronicle posts (A, B, C, & D), the British landlords of Ireland controlled most of the land and used the best pastures for raising animals, which the owners exported to England and other places.

In other words, there was food, but British bias permitted an acceptance of what most today would label genocide.

|

There’s ships leavin’ full of pigs, heifers, and lambs Some transportin’ convicts to Van Diemaen’s Land We’re hemorrhagin’ barrels of butter and grain And all that comes back in and all that remains is… Indian meal, Indian meal, Indian meal. (Van Diemen’s Land was the original name used for the island of Tasmania, now part of Australia.) |

Declan O’Rourke Indian Meal

Indian Meal

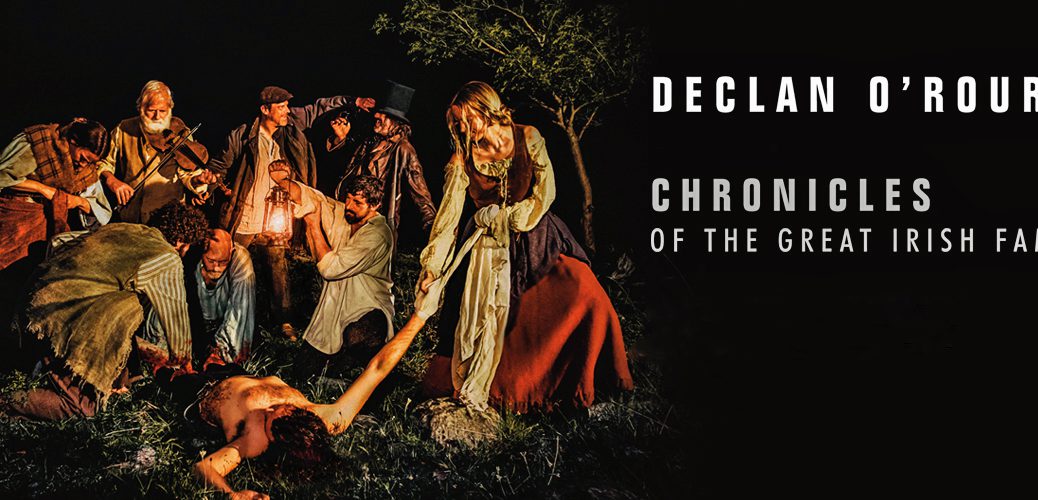

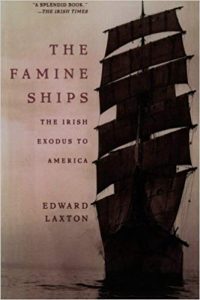

The fifth song of Declan O’Rourke’s Chronicles of the Great Irish Famine album is “Indian Meal.” Once again, the melody belies the message.

The seemingly happy-go-lucky step-dancing tune carries a bitter message: Your potato is gone. Be satisfied with what you can find.

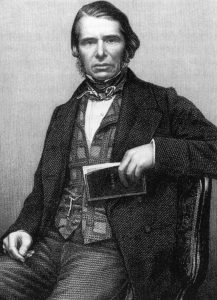

In the midst of the famine, the English changed leadership and charged Sir Charles Edward Trevelyan with famine relief.

According to the History Place site, “ Trevelyan ordered the closing of the food depots in Ireland that had been selling…Indian corn. He also rejected another boatload of Indian corn already headed for Ireland. His reasoning, as he explained in a letter, was to prevent the Irish from becoming “habitually dependent” on the British government. His openly stated desire was to make “Irish property support Irish poverty.”

Declan O’Rourke Indian Meal

Penny a pound

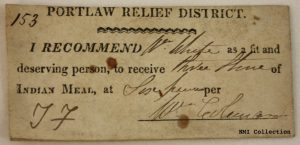

Despite that laissez-faire policy, corn meal did become one of the things that the starving Irish did have access to.

Somewhat.

For a penny a pound. Storehouses often stayed full of Indian meal because the starving who literally stood outside the storehouse, had no money.

Declan O’Rourke Indian Meal

Bothar bui–Yellow Road

|

They’re pavin’ the streets of Americay With gold at your feet for a dollar a day While here on the works we make botharin bui For the yella’ or barely a shillin’ a piece. |

Road workers, in lieu of cash, accepted Indian meal as payment. Ironically, at the same time that myth described the streets of America as “paved with gold,” many roads of Ireland became known as “yellow roads” because workers survived–barely–on the yellow corn meal.

Some rural Irish roads today still contain the name Bothar bui.

For the majority of the Irish, daily life was often a torturous path to death by disease due to starvation.

Declan O’Rourke Indian Meal

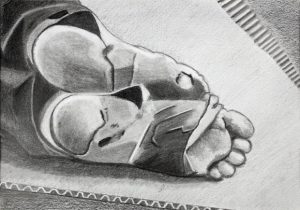

Nicholas Cummins

Again from the History Place site: Nicholas Cummins, the magistrate of Cork, visited the hard-hit coastal district of Skibbereen. “I entered some of the hovels,” he wrote, “and the scenes which presented themselves were such as no tongue or pen can convey the slightest idea of. In the first, six famished and ghastly skeletons, to all appearances dead, were huddled in a corner on some filthy straw, their sole covering what seemed a ragged horsecloth, their wretched legs hanging about, naked above the knees. I approached with horror, and found by a low moaning they were alive — they were in fever, four children, a woman and what had once been a man. It is impossible to go through the detail. Suffice it to say, that in a few minutes I was surrounded by at least 200 such phantoms, such frightful spectres as no words can describe, [suffering] either from famine or from fever. Their demoniac yells are still ringing in my ears, and their horrible images are fixed upon my brain.”