Margaret Sanger Birth Control

The once-seen movie

On May 6, 1917 about 200 people watched a private showing Margaret Sanger’s film, Birth Control. Sanger had scheduled it to open publicly the next night, but New York officials banned it as obscene and it was never shown publicly.

On May 6, 1917 about 200 people watched a private showing Margaret Sanger’s film, Birth Control. Sanger had scheduled it to open publicly the next night, but New York officials banned it as obscene and it was never shown publicly.

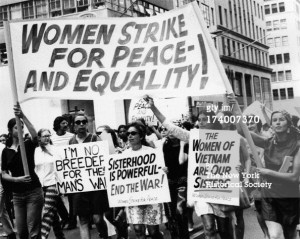

Discomfort regarding sexually-related topics has long been part of American culture. A result of that attitude is that access to reproductive information and obstetric treatment for American women been limited socially as well as legally.

Margaret Sanger Birth Control

Comstock Act

On March 3, 1873 the Comstock Act [named after Anthony Comstock, a U.S. postal inspector] [Case Western article] amended the Post Office Act . Within that act it was illegal to send any “obscene, lewd, and/or lascivious” materials through the mail, including contraceptive devices and information. In addition to banning contraceptives, this act also banned the distribution of information on abortion for educational purposes.

Vestiges of the act endured as the law of the land into the 1990s. In 1971 Congress removed the language concerning contraception, and federal courts until Roe v Wade in 1973 ruled that it applied only to “unlawful” abortions.

After Roe, laws criminalizing transportation of information about abortion remained on the books, and, although they have not been enforced, they have been expanded to ban distribution of abortion-related information on the Internet. [Britannica article]

Margaret Sanger Birth Control

Margaret Sanger

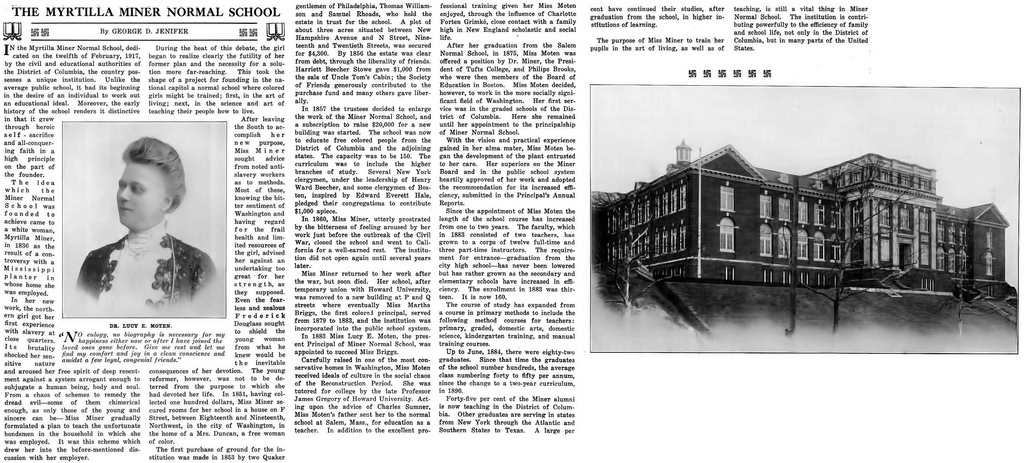

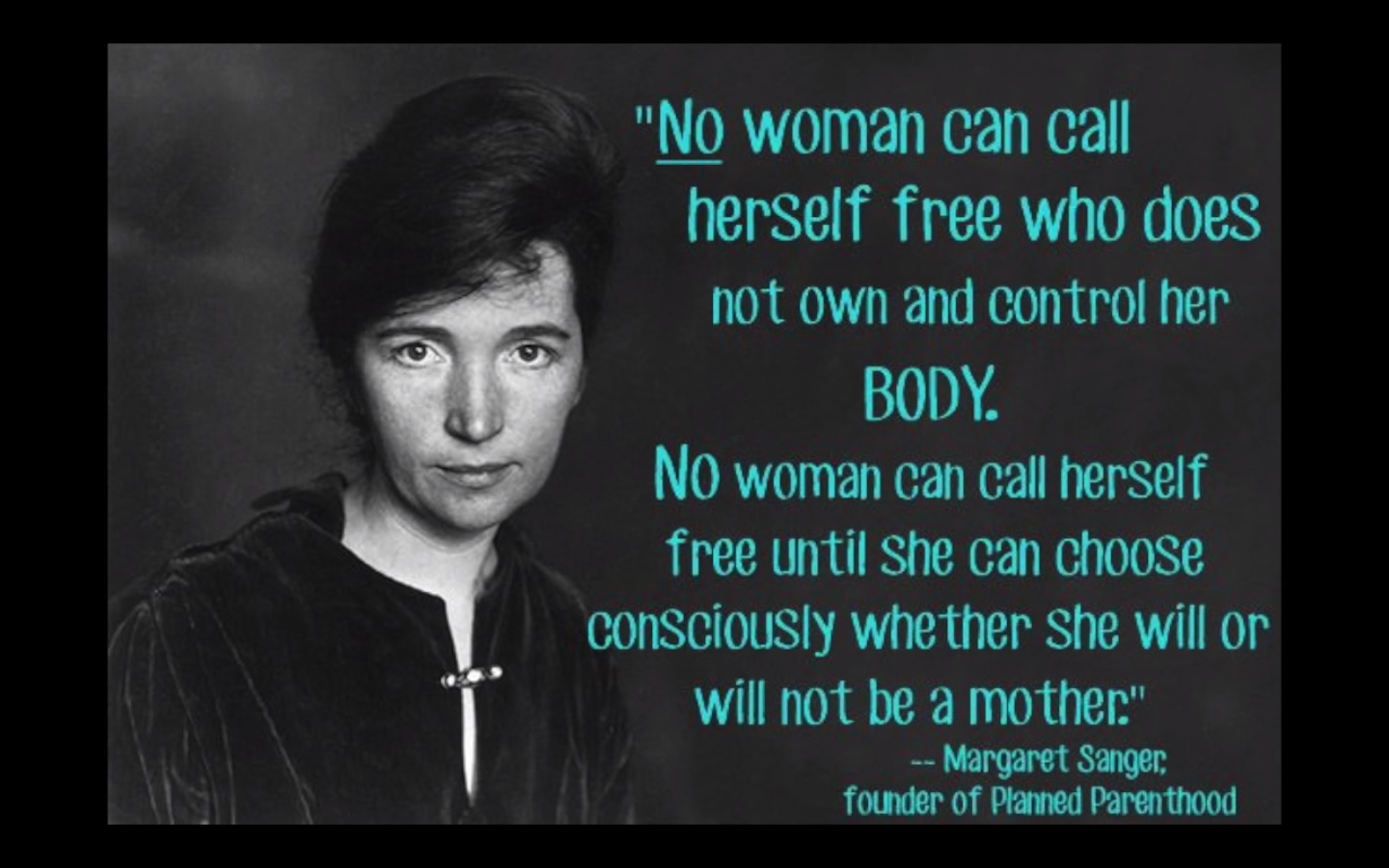

Margaret Sanger, 1879 – 1966, despite her eugenics statements, is in many ways the most important American in terms of reproductive heath care for American women.

Sanger watched her mother Anne die at the age of 49 after she had gone through 18 pregnancies (with 11 live births) in 22 years.

In 1911 she and her husband moved to New York City where, as a visiting nurse, she saw the devastating effects of poverty on health, particularly women’s health.

As an aid to this heath issue, Sanger believed that women needed access to reproductive health information. Her activities in support of that belief were often illegal.

For example: in March 1914, Sanger produced The Woman Rebel [NYU atricle] which instructed women on times when it would be wise for them to avoid pregnancy, such as in the case of illness or poverty. She did not give any instructions regarding specific methods for contraception, but the New York City postmaster banned the journal under the Comstock Law category of “obscene, lewd, lascivious” matter.

Margaret Sanger Birth Control

Clinics

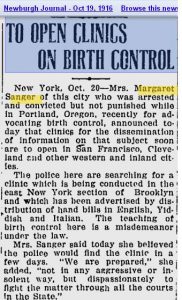

Despite intense social and legal opposition, on October 16, 1916 Sanger and her sister Ethel Byrne [electric beanstalk article] opened the first birth control clinic in the U.S. in Brooklyn. The clinic served 448 people that first day. Ten days later the vice squad raided and shut down the clinic. The squad arrested Sanger and Byrne and confiscated all the condoms and diaphragms at the clinic.

Despite intense social and legal opposition, on October 16, 1916 Sanger and her sister Ethel Byrne [electric beanstalk article] opened the first birth control clinic in the U.S. in Brooklyn. The clinic served 448 people that first day. Ten days later the vice squad raided and shut down the clinic. The squad arrested Sanger and Byrne and confiscated all the condoms and diaphragms at the clinic.

On November 1, 1921 the American Birth Control League was created through a merger of the National Birth Control League and the Voluntary Parenthood League. Led by Sanger, the new league became the leading birth control advocacy group in the country. The American Birth Control League eventually became the Planned Parenthood Federation of America. [Sanger did not like the term planned parenthood and continued to use the phrase “birth control.”

Margaret Sanger Birth Control

Birth control pill

Margaret Sanger’s long term goal was a birth control pill, yet laws against any form of birth control continued to be enacted and upheld in court [February 1, 1943, in Tileston v. Ullman [Cornell article], the Supreme Court upheld a Connecticut law banning the use of drugs or instruments that prevented conception.]

In the early 1940s, researchers began to discover chemicals that could affect ovulation and on April 25, 1951,Margaret Sanger managed to secure a tiny grant for researcher Gregory Pincus from Planned Parenthood. Pincus begins initial work on the use of hormones as a contraceptive. Within a year his research supports the idea, but Planned Parenthood decided not to support further research because it was too risky. In 1953 Sanger was able to gain financial support for Pincus’s research. In 1955 human clinical trials proved that the “pill” was 100% effective.

It was still six years later before the Food and Drug Administration approved the pill. It first went on sale in December 1960. Despite continued social, legal, and religious opposition, by 1964 some four million women were using the drug.

Margaret Sanger Birth Control

Griswold v. Connecticut

On June 7, 1965 in Griswold v. Connecticut (Oyez article), the Supreme Court struck down the one remaining state law prohibiting the use of contraceptives by married couples.

After an adult lifetime of fighting for women’s heath rights, Margaret Sanger died on September 6, 1966. [NYT obit]

Margaret Sanger Birth Control

Racist?

A 2015 Polifact article addressed the accusation that Sanger was a racist in many views, that she supported the Ku Klux Klan.

In her 1938 autobiography, she wrote that she was willing to talk to virtually anyone as she advocated for birth control across the United States: “Always to me any aroused group was a good group, and therefore I accepted an invitation to talk to the women’s branch of the Ku Klux Klan at Silver Lake, New Jersey, one of the weirdest experiences I had in lecturing.”

Sanger later compared the group to children because of their mental simplicity. Jean H. Baker, author of Margaret Sanger: A Life of Passion, said Sanger actually opposed prejudice.

Sanger “was far ahead of her times in terms of opposing racial segregation,” wrote Baker, a history professor at Goucher College, in an email. She worked closely with black leaders to open birth control clinics in Harlem and elsewhere.”

Even authors who treat Sanger critically don’t believe she held negative views about African-Americans. Edwin Black wrote a comprehensive history of the eugenics movement, War Against the Weak, and is no fan of the activist’s beliefs. Ultimately, though, he writes, “Sanger was no racist. Nor was she anti-Semitic.”

Eugenics Aftermath

July 21, 2020: Planned Parenthood of Greater New York announced that it would remove the name of Margaret Sanger, a founder of the national organization, from its Manhattan health clinic because of her “harmful connections to the eugenics movement.”

Sanger had long been lauded as a feminist icon and reproductive-rights pioneer, but her legacy also included supporting eugenics, a discredited belief in improving the human race through selective breeding, often targeted at poor people, those with disabilities, immigrants and people of color.

“The removal of Margaret Sanger’s name from our building is both a necessary and overdue step to reckon with our legacy and acknowledge Planned Parenthood’s contributions to historical reproductive harm within communities of color,” Karen Seltzer, the chair of the New York affiliate’s board, said in a statement. [NYT story]

Racist?

Some say that Sanger supported the Ku Klux Klan (she merely addressed a women’s auxiliary and later compared them to children because of their mental simplicity), Jean H. Baker, author of Margaret Sanger: A Life of Passion, said Sanger actually opposed prejudice.

Sanger “was far ahead of her times in terms of opposing racial segregation,” wrote Baker, a history professor at Goucher College, in an email. She worked closely with black leaders to open birth control clinics in Harlem and elsewhere.”

Even authors who treat Sanger critically don’t believe she held negative views about African-Americans. Edwin Black wrote a comprehensive history of the eugenics movement, War Against the Weak, and is no fan of the activist’s beliefs. Ultimately, though, he writes, “Sanger was no racist. Nor was she anti-Semitic.”