1964 Freedom Summer Riders

SNCC

On March 20, 1964 the Student Non-Violent Coordinating Committee [SNCC–“snick”] announced the “Freedom Summer” program that would train young people to go to Mississippi and help disenfranchised Blacks register to vote.

In 1962, less than 7% of eligible Black voters in Mississippi were registered to vote due to the many blatantly racist laws and customs that States had put into place and the Federal government had allowed.

It had only been on January 23, 1964, thirteen years after its proposal and nearly 2 years after its passage by the US Senate, that the 24th Amendment to the United States Constitution, prohibiting the use of poll taxes in national elections, was ratified. The huge gap was that the amendment applied to national, not local, elections.

1964 Freedom Summer Riders

Civil Rights bill

A Civil Rights bill languished in Congress due to an 83-day filibuster by southern Senators until June 10, 1964 when the Senate voted to limit further debate. On June 19 the Civil Rights Act of 1964 was approved. Voting for the bill were 46 Democrats and 27 Republicans. Voting against it were 21 Democrats and six Republicans. Except for Senator Robert C. Byrd of West Virginia, all the Democratic votes against the bill came from Southerners. Senator Barry Goldwater of Arizona voted against the bill, as he said he would. The five other Republicans opposing it all supported Goldwater’s candidacy for the 1964 Republican Presidential nomination.

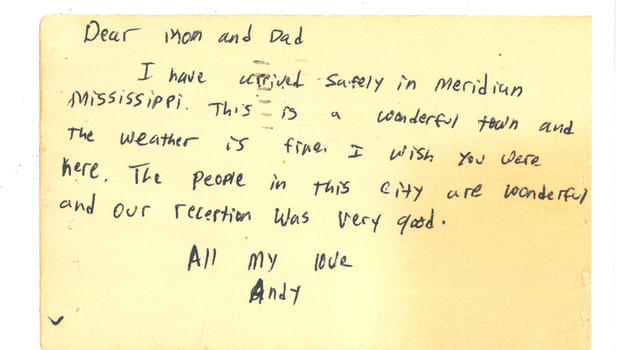

Andrew Goodman

The next day, June 20, 1964, the first “Freedom Summer” volunteers arrived in Mississippi. Andrew “Andy” Goodman, 20, from New York City, was one of them. The next morning he sent a postcard home:

1964 Freedom Summer Riders

Freedom Summer

That same day, Andrew along with James E. Chaney, 21, and Michael Schwerner, 24, went to investigate the burning of a black church.

Police arrested the three on speeding charges, incarcerated them for several hours, and then released them after dark into the hands of the Ku Klux Klan.

Two days later, the station wagon Goodman, Chaney, and Schwerner were driving was found. Burned.

1964 Freedom Summer Riders

Other threats

Meanwhile, on June 24 thirty Freedom Summer workers from Greenville, Miss. made the first effort to register black voters in Drew, Miss., and local whites resisted with open hostility. Whites circled the workers in cars and trucks, some equipped with gun racks, making violent threats. One white man stopped his car and said, “I’ve got something here for you,” flaunting his gun.

Despite an intensive search, the bodies of Goodman, Chaney, and Schwerner were not found until August 4.

1964 Freedom Summer Riders

Freedom Schools

The Freedom Summer workers established 41 Freedom Schools attended by more than 3,000 young black students throughout the state. In addition to math, reading, and other traditional courses, students were also taught black history, the philosophy of the civil rights movement, and leadership skills that provided them with the intellectual and practical tools to carry on the struggle after the summer volunteers departed.

But, voter registration was the cornerstone of the summer project. Although approximately 17,000 black residents of Mississippi attempted to register to vote in the summer of 1964, only 1,600 of the completed applications were accepted by local registrars.

1964 Freedom Summer Riders

Convictions

Three years later, on October 20, 1967 an all-white jury convicted seven conspirators related to the murders of Goodman, Chaney, and Schwerner, including a deputy sheriff. The jury acquitted eight others. It was the first time a white jury had convicted a white official of civil rights killings. For three men, including Edgar Rice Killen, the trial ended in a hung jury, with the jurors deadlocked 11–1 in favor of conviction. The lone holdout said that she could not convict a preacher. The prosecution decided not to retry Killen and he was released.

None of the men found guilty would serve more than six years in prison.

See KKK Murders for expanded story of the Goodman, Chaney, and Schwerner killings.

- Related link >>> History dot com

- Related link >>> King encyclopedia article