Declan O’Rourke Laissez Faire

Declan O’Rourke Laissez Faire

The notion that one should love your neighbor as yourself is obviously as old as the milk of human kindness. The notion that people get what they deserve is equally old.

In the late 17th century, the economic view that the less government is part of a merchant’s business the better for the business and eventually the better for the populace in general came to be known as “Laissez faire.” Translated from the the French, the full term–Laissez-nous faire–means, “Leave it to us.”

Unfortunately, the urge to hold onto increased profits is often stronger than the willingness to share the wealth and the thought of those without falls prey to a different view: they deserve what they get.

The term “Social Darwinism” had not yet entered the language, but the idea that “the fittest or best adapted individuals, or entire societies, prevail” supported the laissez faire view.

Declan O’Rourke Laissez Faire

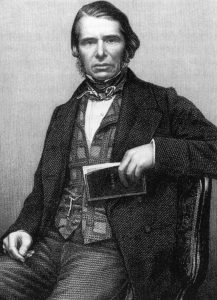

Sir Charles Trevelyan

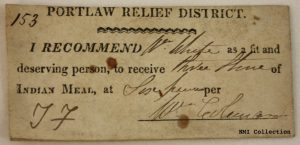

As the potato blight worsened, the British, faced a decision: provide for the poor or let circumstances take their course.

Sir Charles Trevelyan, who had prime responsibility for famine relief in Ireland, decided that the famine was up to God to alleviate since, “The judgement of God sent the calamity to teach the Irish a lesson, that calamity must not be too much mitigated.”

A Trevelyan letter to Edward Twisleton, Chief Poor Law Commissioner in Ireland, contained, “We must not complain of what we really want to obtain. If small farmers go, and their landlords are reduced to sell portions of their estates to persons who will invest capital we shall at last arrive at something like a satisfactory settlement of the country“. [both quotes above are from an Independent article]

O’Rourke’s reply:

Y’er man Travelyan says it’s Laissez Faire

If they were his children he’d fuckin’ well care!

Declan O’Rourke Laissez Faire

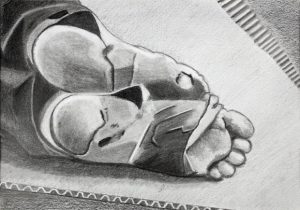

Cities suffered as well

Most Great Irish Famine images are of the countryside and certainly that is where the worst suffering occurred, but cities like Dublin had its share of starvation.

Declan O’Rourke’s wrote Laissez Faire with his poor urban ancestors in mind.

How can I fee ye my beautiful son?

All the goodness I have in my body is gone

How an keep ye my duty be done?

To the blazes I can’t keep ye nourished and strong.

Even when charity appeared, it was sometime offered with strings attached: you must, as a Catholic, become a Protestant:

Swap your Catholic halo for a Protestant hoop

And give up your place in heaven for a bowl of soup.

Those who did became known as “soup takers” to those who remained starving rather than give up their faith.

Declan O’Rourke Laissez Faire

1997

In June 1997, British Prime Minister Tony Blair issued a statement on the Irish Potato Famine. He said “The famine was a defining event in the history of Ireland and Britain. It has left deep scars. That one million people should have died in what was then part of the richest and most powerful nation in the world is something that still causes pain as we reflect on it today. Those who governed in London at the time failed their people.” (Independent article).

Ex post facto is little comfort to those who starved to death or to their descendants.