Change Is Gonna Come

Released December 22, 1964

No Change

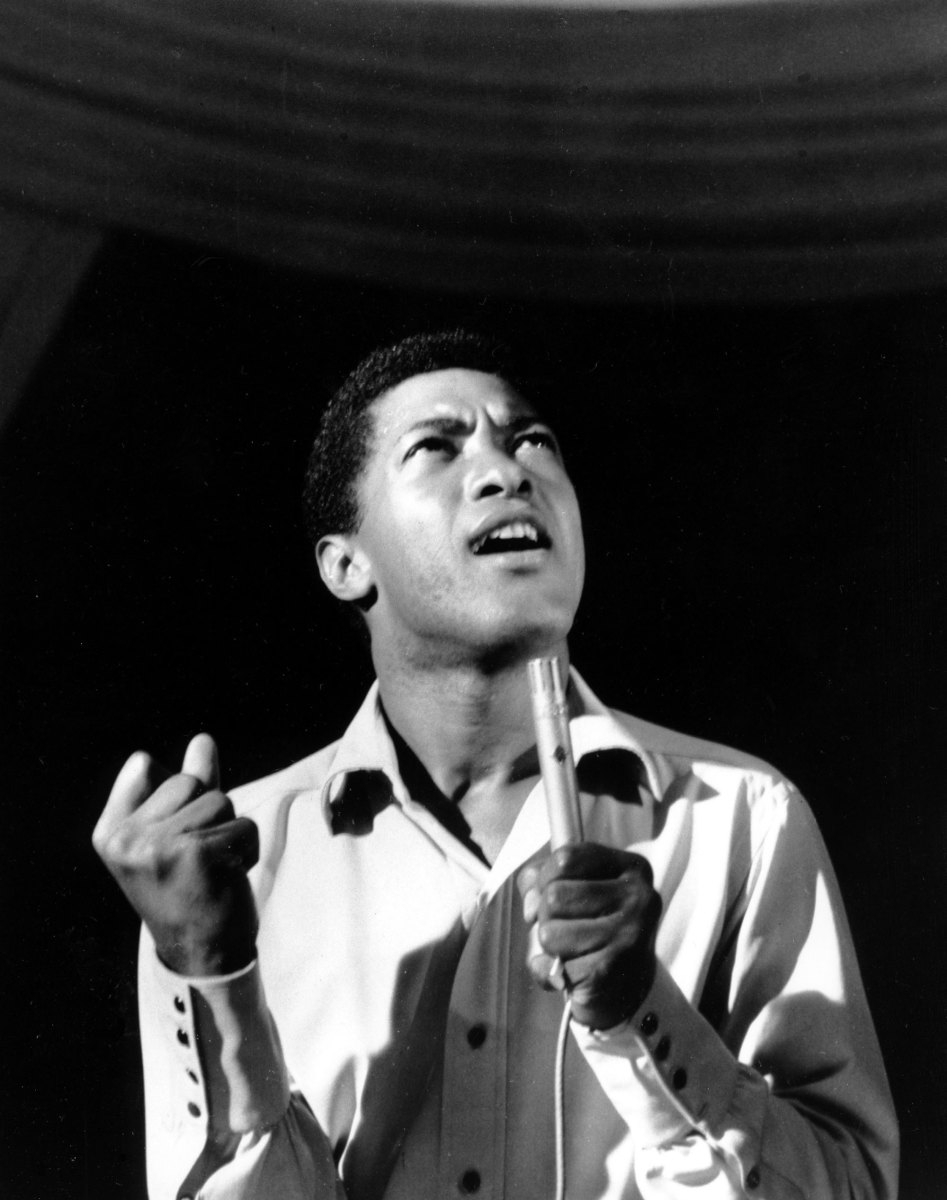

In October 1963 Sam Cooke was touring Louisiana. He had made reservations at a Shreveport Holiday Inn, but when he, his wife, brother, and another arrived, hotel personnel told them that there were no vacancies.

Cooke argued to no avail and left angrily. When they arrived at their next hotel, police arrested them for disturbing the peace.

With the rebirth of the civil rights movement, Black entertainers faced a difficult decision: make a living by catering to the tastes of the majority white audience, most of whom weren’t thrilled with black activism, or musically/philosophically join the civil rights struggle and risk their livelihood.

Bob Dylan’s “Blowin’ In the Wind” surprised Cooke. How could a white person write such a moving song? Cooke began to use the song in his shows.

Change Is Gonna Come

His own change

And Cooke also decided to write his own.

By December 1963 he’d written “A Change is Gonna Come.” In February he performed it live on the Johnny Carson Show (no video available), but had not yet recorded it. Two days after Cooke’s performance on the Tonight Show, the Beatles were on Ed Sullivan.

Change Is Gonna Come

RCA holds off

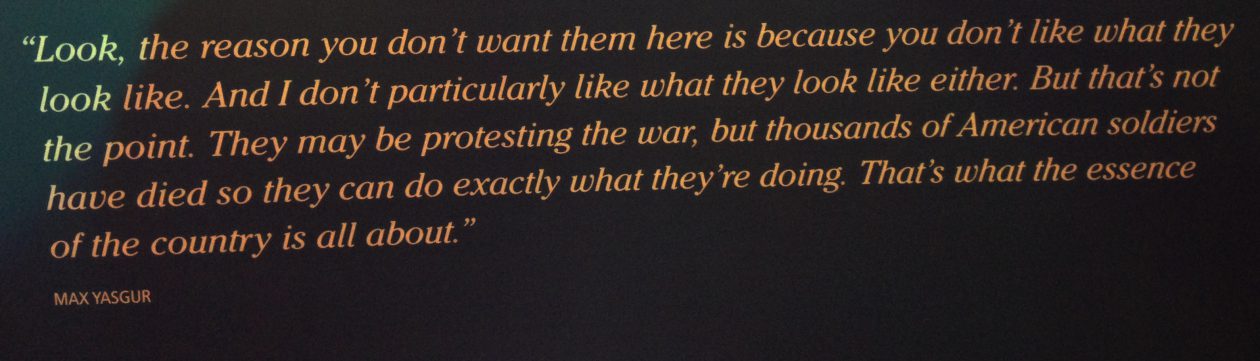

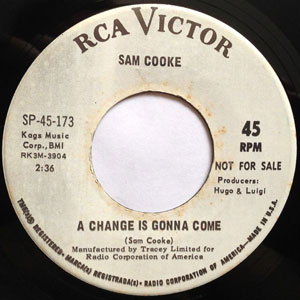

Cooke did not record “A Change is Gonna Come” until November 1964 and RCA did not release it until December.

Sadly, Cooke had died eleven days before on December 11, 1964. (NYT article)

Change Is Gonna Come

Anthem

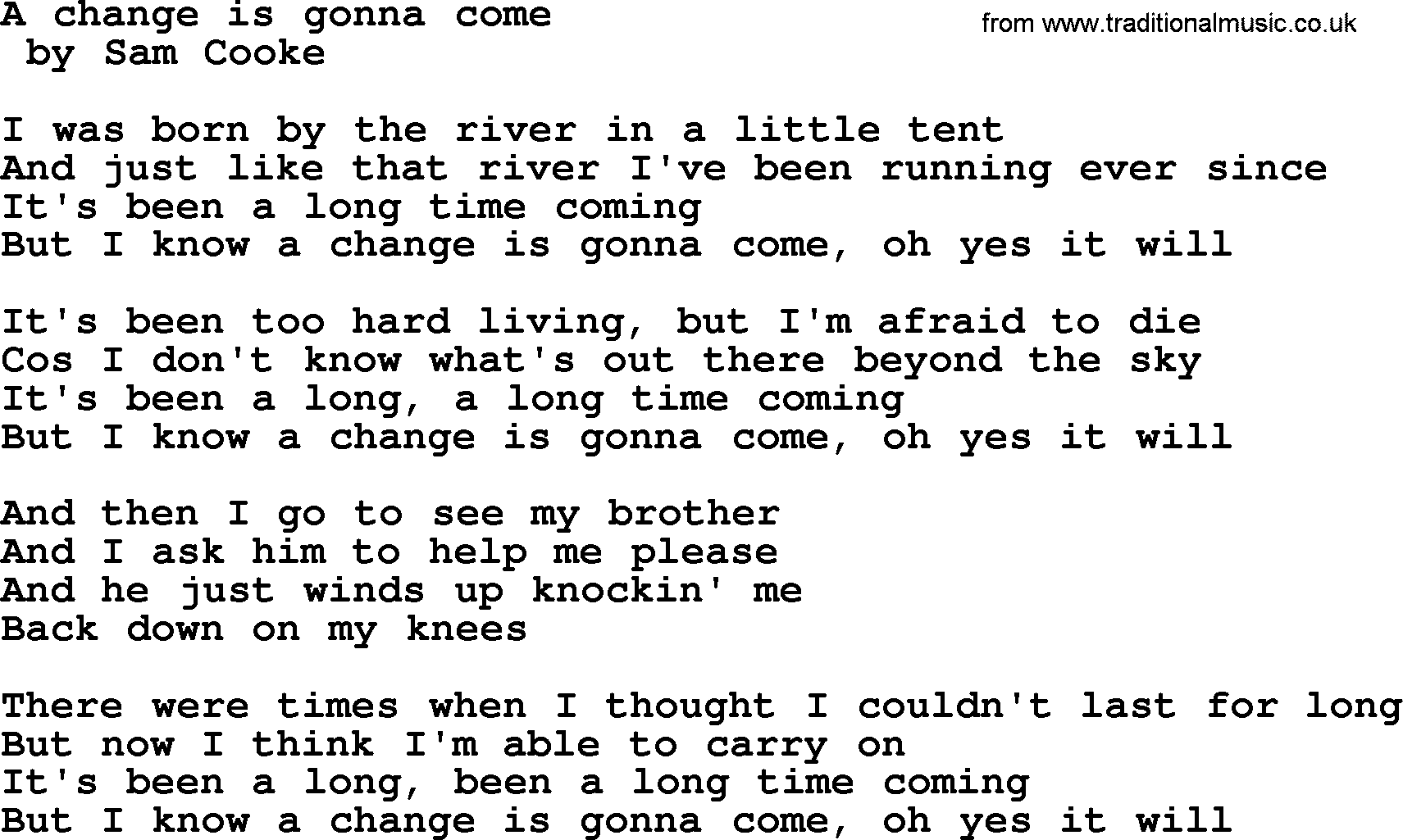

It became one of the civil rights movement’s anthems and dozens of artists have since covered the song.

In 2005, representatives of the music industry and press voted the song number 12 in Rolling Stone magazine’s 500 Greatest Songs of All Time.

Cooke’s style and spirit continue to inspire many of today’s young artists. The New York Times Magazine recently described Leon Bridges as “The Second Coming of Sam Cooke.” (NYT article)