National Women’s Hall of Fame

Formed on February 20, 1969

Happy Anniversary

It’s never too late to learn something new. Today we will start with a matching quiz. In the left column are the names of the outstanding women who were the National Women’s Hall of Fame Class of 2021. The right column lists accomplishments.

Can you match? I could not!

| Patricia Bath | A…an entrepreneur, banker, advocate, and member of the Blackfeet Nation who fought tirelessly for government accountability and for Native Americans to have control over their own financial future |

| Elouise Cobell | B… ophthalmologist, inventor, humanitarian, and academic. She was an early pioneer of laser cataract surgery |

| Kimberlé Crenshaw | C...educational innovator, race relations and feminist activist, author, and public speaker, best known for her seminal 1989 article, “White Privilege: Unpacking the Invisible Knapsack.” |

| Peggy Mcintosh | D...academic, media theorist, author, performance artist, multi-instrumentalist, educator, and programmer. Best known for her groundbreaking 1987 essay, “The Empire Strikes Back: A Posttransexual Manifesto,” Stone is considered a founder of the academic discipline of transgender studies. |

| Judith Plaskow | E… pathologist and pioneer in the study of immune responses to infectious diseases at the turn of the 20th century. Over the course of her research career, she worked on developing vaccines, treatments, and diagnostic tests for many diseases, including diphtheria, rabies, scarlet fever, smallpox, influenza, and meningitis. |

| Loretta Ross | F… theologian, author, and activist known for being the first Jewish feminist theologian. She earned her doctorate from Yale University in 1975 and spent over three decades teaching Religious Studies at Manhattan College |

| Sandy Stone | G… pioneering scholar and writer on civil rights, critical race theory, Black feminist legal theory, and race, racism, and the law. |

| Anna Wessels Williams | H...academic, feminist, and activist for reproductive justice, especially among women of color. Driven by her personal experiences as a survivor of rape and nonconsensual sterilization, Ross has dedicated her extensive career in academia and activism to reframing reproductive rights within a broader context of human rights. |

National Women’s Hall of Fame

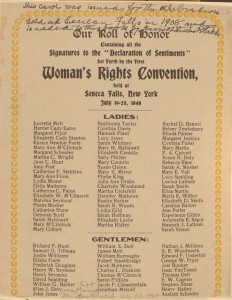

Seneca Falls

A group of men and women founded the National Women’s Hall of Fame on February 20, 1969 in Seneca Falls, New York. where Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Lucretia Mott, two renowned leaders of the US suffragette movement, organized the first Women’s Right Convention at Seneca Falls in 1848.

Showcasing great women

The Hall of Fame’s mission is, “Showcasing great women…Inspiring all!”

According to its site: National Women’s Hall of Fame is open on the 1st floor of the historic Seneca Knitting Mill on the Seneca-Cayuga branch of the Erie Canal in Seneca Falls, New York. Our introductory exhibits are designed to show the world our vision for the future exhibits when we complete additional renovations of the Mill, celebrate Inductees, and showcase stimulating stories of past and present hard-won achievements.

Included in the introductory exhibits is a new Hall of Fame display listing our Inductees and their areas of accomplishment that visitors can browse. There is a section called “Why Here?” highlighting why all of this history happened in Seneca Falls. We tell the story of the Seneca Knitting Mill and the women who worked there. We invite visitors to delve into the history of what happens when women innovate or lead with an interactive exhibit that challenges widely-held assumptions. Visitors can “weave” themselves into the story in a participatory exhibit, and we ask visitors for their own stories of women who have inspired them. The exhibits encourage visitors to engage in creating our future and to understand the possibility of a world where women are equal partners in leadership.

National Women’s Hall of Fame

Here is an informative 2-minute introduction about the Hall by a few of the women who are members, watch the following:

National Women’s Hall of Fame

Who’s who?

2023 Inductees

Patricia Era Bath (1942 – 2019) was an American ophthalmologist, inventor, humanitarian, and academic. She was an early pioneer of laser cataract surgery and was the first Black woman physician to receive a medical patent, which she received in 1986, for the Laserphaco Probe and technique, which performed all steps of cataract removal.

She became the first woman member of the Jules Stein Eye Institute, the first woman to lead a post-graduate training program in ophthalmology, and she was the first woman elected to the honorary staff of the UCLA Medical Center. Bath was the first Black person to serve as a resident in ophthalmology at New York University and was also the first Black woman to serve on staff as a surgeon at the UCLA Medical Center. She became the first Black woman physician to receive a patent for a medical purpose and would go on to earn a total of five patents during her lifetime. Bath is also recognized for her founding of the American Institute for the Prevention of Blindness, a nonprofit located in Washington, D.C.

Elouise Pepion Cobell (1945 – 2011) (“Yellow Bird Woman”) was an entrepreneur, banker, advocate, and member of the Blackfeet Nation who fought tirelessly for government accountability and for Native Americans to have control over their own financial future. Cobell was first appointed as the treasurer for the Blackfeet Nation, and went on to found the Blackfeet National Bank, now part of the Native American Bank, the first national bank located on a Native American reservation and established by a Tribe in the United States. In 2001, 20 tribal nations and Alaska Native corporations joined in the newly launched Native American Bank. Today, 31 tribes participate in the Bank which has assets of $128 million and provides financing across Indian country. In 1997, Cobell was named a MacArthur Fellow for her work in support of tribal banking self-determination and financial literacy education.

On June 10, 1996, Cobell and the Native American Rights Fund filed a class-action lawsuit against the U.S. Department of the Interior for the mismanagement of Indian Trust Funds owed to over 300,000 individual tribal members. The lawsuit alleged that the Bureau of Indian Affairs mismanaged and abused the Indian Trust Funds for over a century, resulting in high poverty rates for Native Americans. Elouise Cobell was not only the lead plaintiff on Cobell v. Salazar, but also raised money for the lawsuit, donating part of her MacArthur Genius Grant to the cause. After 13 years of arduous court battles, the federal government settled for $3.4 billion. It was 16-years by the time Congress ratified the settlement.

Kimberlé W. Crenshaw is a pioneering scholar and writer on civil rights, critical race theory, Black feminist legal theory, and race, racism, and the law. She currently holds positions with Columbia Law School and the University of California, Los Angeles.

Peggy McIntosh is an educational innovator, race relations and feminist activist, author, and public speaker, best known for her seminal 1989 article, “White Privilege: Unpacking the Invisible Knapsack.” She derived her understanding of white privilege from observing parallels with male privilege, and her work has been instrumental in introducing the dimension of privilege, or unearned power, into discussions of gender, race, sexuality, and colonialism.

Judith Plaskow is an American theologian, author, and activist known for being the first Jewish feminist theologian. She earned her doctorate from Yale University in 1975 and spent over three decades teaching Religious Studies at Manhattan College. Plaskow launched the Journal of Feminist Studies in Religion in 1985 and served as the journal’s editor for its first 10 years and from 2012 to 2016. Plaskow also helped found B’not Esh, a Jewish feminist spirituality collective and served as president of the American Academy of Religion.

Loretta J. Ross is a Black academic, feminist, and activist for reproductive justice, especially among women of color. Driven by her personal experiences as a survivor of rape and nonconsensual sterilization, Ross has dedicated her extensive career in academia and activism to reframing reproductive rights within a broader context of human rights. Over her decades of grassroots organizing and national strategic leadership, Ross has centered the voices and well-being of women of color.

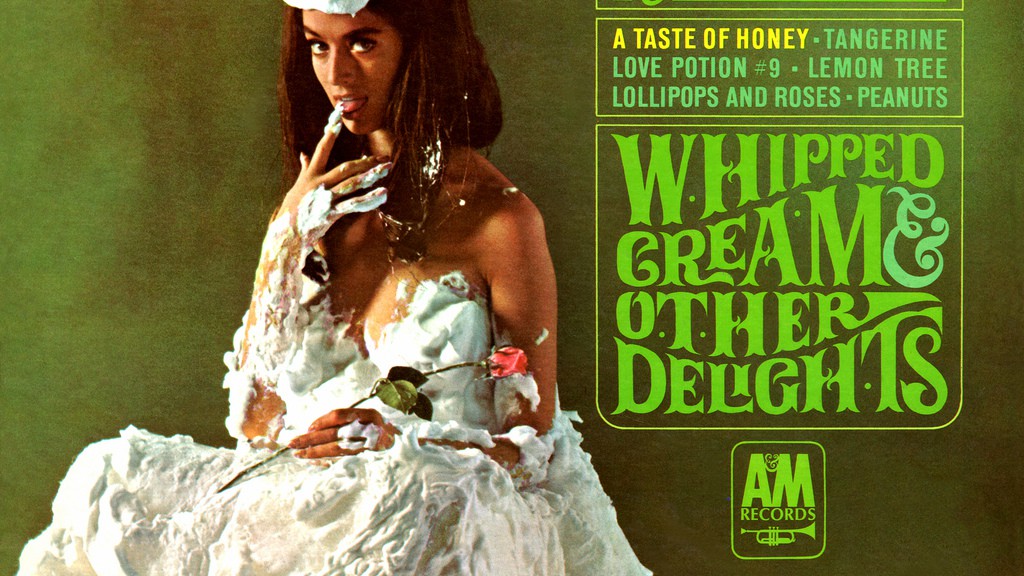

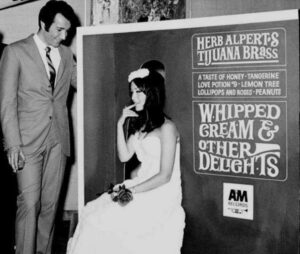

Allucquére Rosanne Stone, also known as Sandy Stone, is an academic, media theorist, author, performance artist, multi-instrumentalist, educator, and programmer. Best known for her groundbreaking 1987 essay, “The Empire Strikes Back: A Posttransexual Manifesto,” Stone is considered a founder of the academic discipline of transgender studies. She is currently Associate Professor Emerita and Founding Director of the Advanced Communication Technologies Laboratory (ACTLab) at the University of Texas at Austin. She is also the Wolfgang Kohler Professor of Media and Performance at the European Graduate School in Saas-Fee, Switzerland, Fellow of the University of California Humanities Research Institute, and Banff Centre Senior Artist.

Anna Wessels Williams (1863-1954) was an American pathologist and pioneer in the study of immune responses to infectious diseases at the turn of the 20th century. Over the course of her research career, she worked on developing vaccines, treatments, and diagnostic tests for many diseases, including diphtheria, rabies, scarlet fever, smallpox, influenza, and meningitis. Notably, Williams worked at the New York City Department of Health’s diagnostic laboratory specifically on projects that tackled diphtheria. In her first year at the lab, she isolated a strain of the diphtheria bacillus which could be used to produce the antitoxin for diphtheria in large quantities. This fundamental discovery increased the availability of the antitoxin and cut production costs, which was crucial to controlling the devastating disease. Within a year of Williams’ discovery, the antitoxin was being shipped to doctors in the United States.