Tulsa Race Massacre

The Greenwood neighborhood of Tulsa, Oklahoma had earned the nickname America’s Black Wall Street. By 1921, it was a 35-block neighborhood with a bustling retail scene, as well as two schools, two newspapers and a hospital. Dozens of successful black-owned, black-run businesses were there. Hundreds of Blacks lived within walking distance of grocery stores, hotels, nightclubs, billiard halls, theaters, doctor’s offices and churches.

It was a city within a city.

Tulsa Race Massacre

Post Civil War

According to a New York Times article, “Many African-Americans migrated to Tulsa after the Civil War, carrying dreams of new chapters and the kind of freedom found in owning businesses. Others made a living working as maids, waiters, chauffeurs, shoe shiners and cooks for Tulsa’s new oil class.

In Greenwood, residents held more than 200 different types of jobs. About 40 percent of the community’s residents were professionals or skilled craftspeople, like doctors, pharmacists, carpenters and hairdressers, according to a Times analysis of the 1920 census. While a vast majority of the neighborhood rented, many residents owned their homes.”

Though Blacks enjoyed success within Greenwood, as with all areas in the United States, the majority white Tulsa community continued to deny them access to society in general.

Tulsa Race Massacre

May 30 and June 1, 1921

On May 30, 1921 there was an elevator incident. As with nearly all such incidents, the truth is likely not close to the stories that were told.

The incident involved Dick Rowland, 19, a young Black shoe shiner, and Sarah Page, 17, a white elevator operator and likely was that Rowland tripped and grabbed onto the arm of Page while trying to catch his fall. She screamed, and he ran away, according to the 200-page 1921 Tulsa Race Massacre Centennial Commission report released on February 28, 2001.

Tulsa Race Massacre

May 31, 1921

Authorities arrest Dick Rowland the following day and jailed him in the Tulsa County Courthouse. As usual, the white-owned newspapers inflamed white Tulsa residents with the headline: “Nab Negro for Attacking Girl in Elevator.”

While any report, however spurious, of any Black person’s “disrespect” of a White person was cause for revenge, the interaction between a Black male and a White female was particularly provoking.

A lynch mob showed up outside the Courthouse. Twice, a group of armed Black Tulsans, many of them World War I veterans, offered to help protect Rowland but the sheriff turned them away.

As the men left the second time, a white man tried to disarm one of the black men. His weapon discharged and that sparked the always-simmering excuse to teach “them” a lesson.

Later, authorities would drop the charges against Rowland and concluded that he had most likely tripped and stepped on the Page’s foot, but that conclusion came far too late.

Tulsa Race Massacre

2-days of Destruction

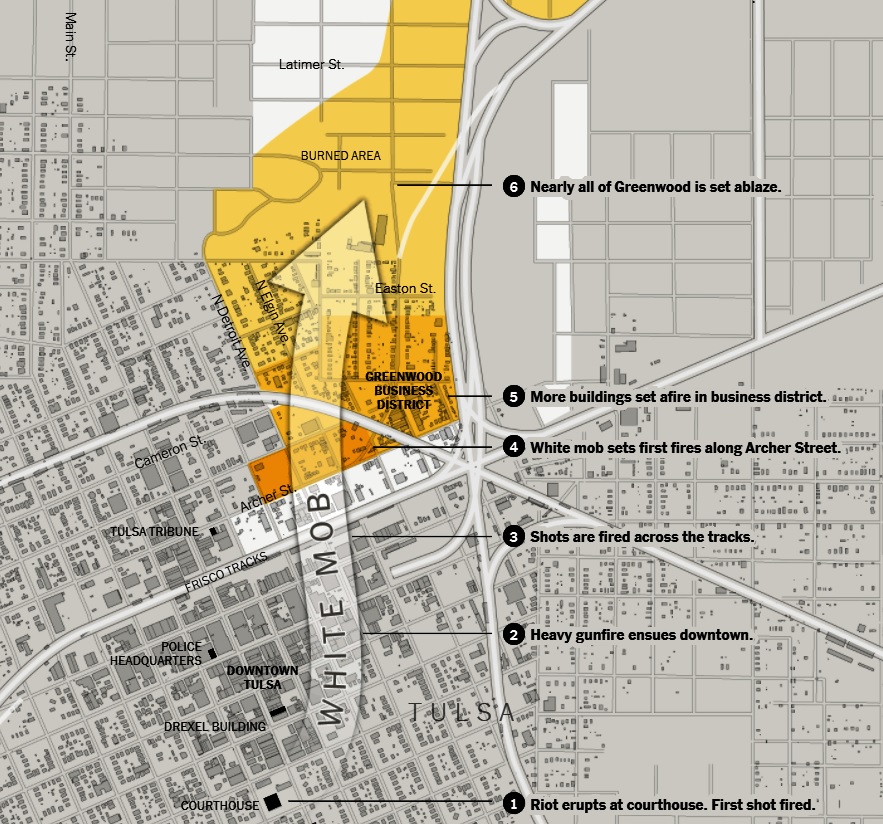

A white mob descended on Greenwood.

Again according to the NY Times article, The mob “…indiscriminately shot Black people in the streets, ransacked homes, stole money and jewelry.

“They set fires, “house by house, block by block,” according to the commission report.

“Terror came from the sky, too. White pilots flew airplanes that dropped dynamite over the neighborhood, the report stated, making the Tulsa aerial attack what historians call among the first of an American city.

“The numbers presented a staggering portrait of loss: 35 blocks burned to the ground; as many as 300 dead; hundreds injured; 8,000 to 10,000 left homeless; more than 1,470 homes burned or looted.”

Another article speaks about members of the Oklahoma National Guard arresting Black victims and detaining 6,000 Greenwood residents at the Convention Hall and the Fairgrounds, some for as long as eight days.

Tulsa Race Massacre

Silent Aftermath

Though some Black residents attempted to stay and rebuilt, it never again was America’s Black Wall Street.

Tulsa passed a fire ordinance intended to prevent Black property owners from rebuilding on their own and insurance companies that refused to pay damage claims.

Tulsa hid the story. Decades later when some young Black college students from Tulsa learned of the Massacre, they responded with disbelief how effective the secret keeping had been.

No one was ever prosecuted or punished for the Massacre and in 2005, the Supreme Court declined to hear a case brought by massacre victims, who appealed the decision of two federal court judges who said the victims waited too long to file their lawsuit.

July 9, 2023: there had been a lawsuit regarding compensation but on this date Oklahoma Judge Caroline Wall threw out the lawsuit.

August 16, 2023: the Oklahoma Supreme Court agreed to hear an appeal of July 9 dismissal of the lawsuit filed by the attack’s last at the time three living survivors.

June 12, 2024: the Oklahoma Supreme Court affirmed the lower court’s dismissal of the lawsuit.

The ruling concluded the lawsuit that Lessie Benningfield Randle, 109, and Viola Ford Fletcher, 110, filed in 2020. Another survivor of the massacre, Hughes Van Ellis, the younger brother of Ms. Fletcher, died at 102 in October 2023.

The justices ruled that the plaintiffs’ grievances, including any lingering economic and social impact of the massacre, “do not fall within the scope of our state’s public nuisance statute” and do not support a claim for reparations.

“The continuing blight alleged within the Greenwood community born out of the Massacre implicates generational-societal inequities that can only be resolved by policymakers — not the courts,” the ruling stated. [NYT article]

* * * * * *

Here is a link to many photos related to the Massacre.

And here a link to an excellent Smithsonian Magazine article entitled Artifacts From the Tulsa Race Massacre.