Auto Lite Battle of Toledo

Strike Begins

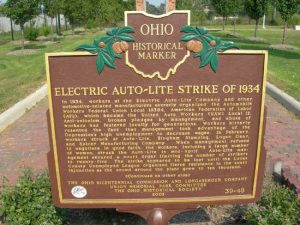

April 12, 1934: the Toledo (Ohio) Auto-Lite strike began with 6,000 workers demanding union recognition and higher pay. The strike was notable for a 5-day running battle in late May between the strikers and 1,300 members of the Ohio National Guard.

Known as the “Battle of Toledo,” the clash left two strikers dead and more than 200 injured. The 2-month strike, a win for the workers’ union, is regarded by many labor historians as one of the nation’s three most important strikes.

Auto Lite Battle of Toledo

Battle Begins…Wednesday 23 May

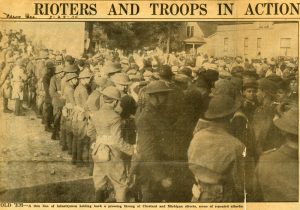

May 23, 1934: at the Toledo Auto-Lite strike, the sheriff of Lucas County (Ohio) decided to take action against the picketers. In front of a crowd which now numbered nearly 10,000, sheriff’s deputies arrested five picketers. As the five were taken to jail, a deputy began beating an elderly man. Infuriated, the crowd began hurling stones, bricks and bottles at the sheriff’s deputies. A fire hose was turned on the crowd, but the mob seized it and turned the hose back on the deputies.

Many deputies fled inside the plant gates, and Auto-Lite managers barricaded the plant doors and turned off the lights. The deputies gathered on the roof and began shooting tear gas bombs into the crowd. So much tear and vomit gas was used that not even the police could enter the riot zone.

The mob retaliated by hurling bricks and stones through the plant’s windows for seven hours. The strikers overturned cars in the parking lot and set them ablaze. The inner tubes of car tires were turned into improvised slingshots, and bricks and stones launched at the building. Burning refuse was thrown into the open door of the plant’s shipping department, setting it on fire. In the early evening, the rioters attempted to break into the plant and seize the replacement workers, security personnel and sheriff’s deputies.

Police fired shots at the legs of rioters to try to stop them. The gunfire was ineffective, and only one person was (slightly) wounded. Hand-to-hand fighting broke out as the rioters broke into the plant. The mob was repelled, but tried twice more to break into the facility before they gave up late in the evening. More than 20 people were reported injured during the melee. Auto-Lite president Clement O. Miniger was so alarmed by the violence that he ringed his home with a cordon of armed guards. [libcom dot org article]

Auto Lite Battle of Toledo

National Guard/Thursday

May 24, 1934: Ohio National Guardsmen, most of them teenagers, arrived in a light rain. The troops included eight rifle companies, three machine-gun companies and a medical unit. The troops cleared a path through the picket line, and the sheriff’s deputies, private security guards and replacement workers were able to leave the plant.

May 24, 1934: Ohio National Guardsmen, most of them teenagers, arrived in a light rain. The troops included eight rifle companies, three machine-gun companies and a medical unit. The troops cleared a path through the picket line, and the sheriff’s deputies, private security guards and replacement workers were able to leave the plant.

Later that morning, Judge Stuart issued a new injunction banning all picketing in front of the Auto-Lite plant, but the picketers ignored the order.

During the afternoon, President Roosevelt sent Charles Phelps Taft II, son of the former president, to Toledo by to act as a special mediator in the dispute. AFL president William Green sent an AFL organizer to the city as well to help the local union leadership bring the situation under control.

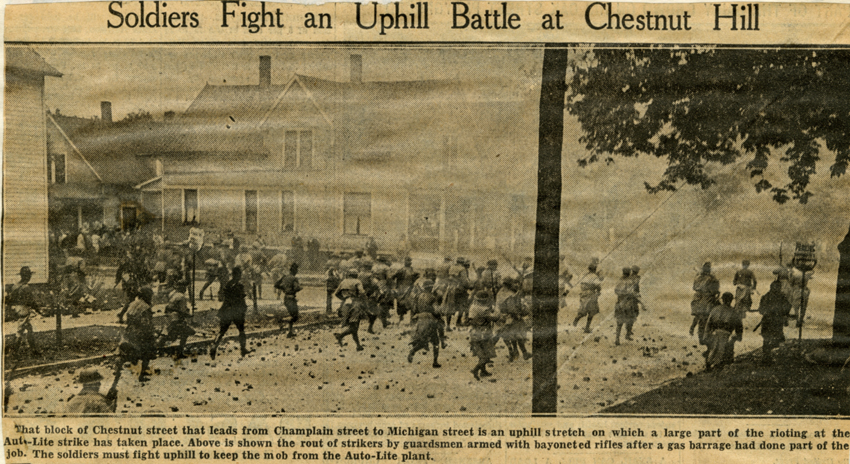

During the late afternoon and early evening of May 24, a huge crowd of about 6,000 people gathered again in front of the Auto-Lite plant. Around 10 p.m., the crowd began taunting the soldiers and tossing bottles at them. The militia retaliated by launching a particularly strong form of tear gas into the crowd. The mob picked up the gas bombs and threw them back. For two hours, the gas barrage continued. Finally, the rioters surged back toward the plant gates. The National Guardsmen charged with bayonets, forcing the crowd back. Again the mob advanced. The soldiers fired into the air with no effect, then fired into the crowd—killing 27-year-old Frank Hubay (shot four times) and 20-year-old Steve Cyigon. Neither was an Auto-Lite worker, but had joined the crowd out of sympathy for the strikers. At least 15 others also received bullet wounds, while 10 Guardsmen were treated after being hit by bricks.

A running battle occurred throughout the night between National Guard troops and picketers in a six-block area surrounding the plant. A smaller crowd rushed the troops again a short time after Hubay and Cyigon’s deaths, and two more picketers were injured by gunfire. A company of troops was sent to guard the Bingham Tool and Die plant, a squad of sheriff’s deputies dispatched to protect the Logan Gear factory, and another 400 National Guardsmen ordered to the area. Nearly two dozen picketers and troopers were injured by hurled missiles during the night. The total number of troops now in Toledo was 1,350, the largest peace-time military build-up in Ohio history. [people’s world dot org article]

Auto Lite Battle of Toledo

Plant closed/Friday

May 25, 1934: Auto-Lite officials agreed to keep the plant closed in an attempt to forestall further violence and Auto-Lite President Clement Miniger was arrested after local residents swore out complaints that he had created a public nuisance by allowing his security guards to bomb the neighborhood with tear gas. Strike leader Louis Budenz, too, was arrested—again on contempt of court charges.

May 25, 1934: Auto-Lite officials agreed to keep the plant closed in an attempt to forestall further violence and Auto-Lite President Clement Miniger was arrested after local residents swore out complaints that he had created a public nuisance by allowing his security guards to bomb the neighborhood with tear gas. Strike leader Louis Budenz, too, was arrested—again on contempt of court charges.

Meanwhile, rioting continued throughout the area surrounding the Auto-Lite plant. Furious local citizens accosted National Guard troops, demanding that they stop gassing the city. Twice during the day, troops fired volleys into the air to drive rioters away from the plant. A trooper was shot in the thigh, and several picketers were severely injured by flying gas bombs and during bayonet charges. In the early evening, when the National Guard ran out of tear gas bombs, they began throwing bricks, stones and bottles back at the crowd to keep it away.

The AFL’s Committee of 23 announced that 51 of the city’s 103 unions had voted to support a general strike.

That evening, local union members voted down a proposal to submit all grievances to the Automobile Labor Board for mediation. The plan had been offered by Auto-Lite officials the day before and endorsed by Taft. But the plan would have deprived the union of its most potent weapon (the closed plant and thousands of picketing supporters) and forced the union to accept proportional representation. Union members refused to accept either outcome. Taft suggested submitting all grievances to the National Labor Board instead, but union members rejected that proposal as well. [NYT article]

Auto Lite Battle of Toledo

Violence abates/Saturday

May 26, 1934: the violence began to die down somewhat. Troopers began arresting hundreds of people, most of whom paid a small bond and won release later the same day. Large crowds continued to gather in front of the Auto-Lite plant and hurl missiles at the troops, but the National Guard was able to maintain order during daylight hours without resorting to large-scale gas bombing. During the day, strike leader Ted Selander was arrested by the National Guard and held incommunicado. Despite pleas, Taft refused to use his influence to have Selander freed or his whereabouts revealed. With two of the AWP’s three local leaders in jail, the AWP was unable to mobilize as many picketers as before. Although a crowd of 5,000 gathered in the early evening, the National Guard was able to disperse the mob after heavily gassing the six-block neighborhood.

May 26, 1934: the violence began to die down somewhat. Troopers began arresting hundreds of people, most of whom paid a small bond and won release later the same day. Large crowds continued to gather in front of the Auto-Lite plant and hurl missiles at the troops, but the National Guard was able to maintain order during daylight hours without resorting to large-scale gas bombing. During the day, strike leader Ted Selander was arrested by the National Guard and held incommunicado. Despite pleas, Taft refused to use his influence to have Selander freed or his whereabouts revealed. With two of the AWP’s three local leaders in jail, the AWP was unable to mobilize as many picketers as before. Although a crowd of 5,000 gathered in the early evening, the National Guard was able to disperse the mob after heavily gassing the six-block neighborhood.

Auto Lite Battle of Toledo

Picketing ceases/Sunday

May 27, 1934: almost all picketing and rioting within the now eight-block-wide zone surrounding the Auto-Lite plant ceased.

Mediation/Monday

May 28, 1934: the union agreed to submit their grievances to mediation, but Auto-Lite officials refused these terms. A company union calling itself the Auto-Lite Council injected itself into the negotiations, demanding that all replacement workers be permitted to keep their jobs. In contrast, the union demanded that all strikebreakers be fired. Meanwhile, Judge Stuart began processing hundreds of contempt of court cases associated with the strike. Arthur Garfield Hays, general counsel for the American Civil Liberties Union, traveled to Toledo and represented nearly all those who came before Judge Stuart. [NYT article]

Impasse/Tuesday

May 29, 1934: tensions worsened again. The Toledo Central Labor Council continued to plan for a general strike. By now, 68 of the 103 unions had voted to support a general strike, and the council was seeking a vote of all its member unions on Thursday, May 31. Auto-Lite executives, too, were busy. Miniger met with Governor George White and demanded that White re-open the plant using the National Guard. White refused, but quietly began drawing up contingency plans to declare martial law. Negotiations remained deadlocked, and Taft began communicating with United States Secretary of Labor Frances Perkins to seek federal support (including personal intervention by Roosevelt). [NYT article] (see May 31)

Auto Lite Battle of Toledo

Central Labor Council/Wednesday

May 30, 1934: the Toledo Central Labor Council asked President Roosevelt to intervene to avert a general strike. The CLC placed the final decision to hold a general strike in the hands of the Committee of 23, with a decision to be rendered on June 2. By this time, 85 of the CLC’s member unions had pledged to support the general strike (with one union dissenting and another reconsidering its previous decision to support the general strike). The same day, leaders of FLU [federal labor union] 18384 met with Governor White and presented their case. The media reported that both Labor Secretary Perkins and AFL president Green might come to Toledo to help end the strike. Despite no resolution to the strike, Toledo remained peaceful. Governor White had begun withdrawing National Guard troops a few days earlier, and by May 31 only 250 remained.

Auto Lite Battle of Toledo

Tentative Agreement/Saturday

June 2, 1934: Auto-Lite and FLU 18384 reached a tentative agreement settling the strike. The union won a 5 percent wage increase, and a minimum wage of 35 cents an hour. The union also won recognition (effectively freezing out the company union), provisions for arbitration of grievances and wage demands, and a system of re-employment which favored (respectively) workers who had crossed the picket line, workers who struck, and replacement workers. Although Muste and Budenz advocated that the union reject the agreement, workers ratified it on June 3.

June 2, 1934: Auto-Lite and FLU 18384 reached a tentative agreement settling the strike. The union won a 5 percent wage increase, and a minimum wage of 35 cents an hour. The union also won recognition (effectively freezing out the company union), provisions for arbitration of grievances and wage demands, and a system of re-employment which favored (respectively) workers who had crossed the picket line, workers who struck, and replacement workers. Although Muste and Budenz advocated that the union reject the agreement, workers ratified it on June 3.

Sometimes bitter legacy

April 12, 1996: (from the historymike blog) “At the memorial for the old Auto-Lite plant display floodlights have been smashed, a brass picket has been ripped from the hands of the brass striker who held it, and trash is strewn about the site.

April 12, 1996: (from the historymike blog) “At the memorial for the old Auto-Lite plant display floodlights have been smashed, a brass picket has been ripped from the hands of the brass striker who held it, and trash is strewn about the site.

“Scrawled on the remains of the brass picket is the name “Hitler.””