Recording Engineer Rudy Van Gelder

November 2, 1924 – August 25, 2016

The genesis for this site began with a request. I was training to be a docent at Bethel Woods Center for the Arts and the group leader asked if anyone was interested in doing a presentation on protest music of the 1960s.

Hubris overflowing, I confidently volunteered.

As I began to gather information, I quickly found myself spiraling down the proverbial rabbit hole. Not only did I “discover” that protest music had been around long before the 60s, but that it was still around.

The next thing I discovered was that to understand protest music, we have to place it in context. What were times in which the artist wrote the lyrics?

Soon, that expansion led to another realization: that as traditional as protest music was, other art forms also have had their revolutions.

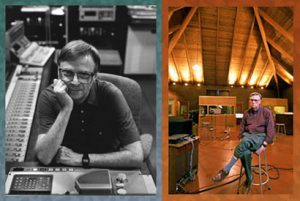

Recording Engineer Rudy Van Gelder

Rudy Van Gelder

According to Steve Huey’s bio of Rudy Van Gelder at the All Music site, “Rudy Van Gelder was, quite simply, the greatest recording engineer in jazz history. He was responsible for just about every session on the Blue Note label from 1953 to 1967 (among thousands of others), encompassing some of jazz’s most groundbreaking and enduring classics.”

Recording Engineer Rudy Van Gelder

Hackensack, NJ

Living in northern NJ, I was surprised to find that part of that musical revolution happened in my own backyard.

Living in northern NJ, I was surprised to find that part of that musical revolution happened in my own backyard.

During the counter-cultural decade, jazz musicians were also experimenting with their music and that experimentation coincided with technological advances to record with a quality theretofore unavailable.

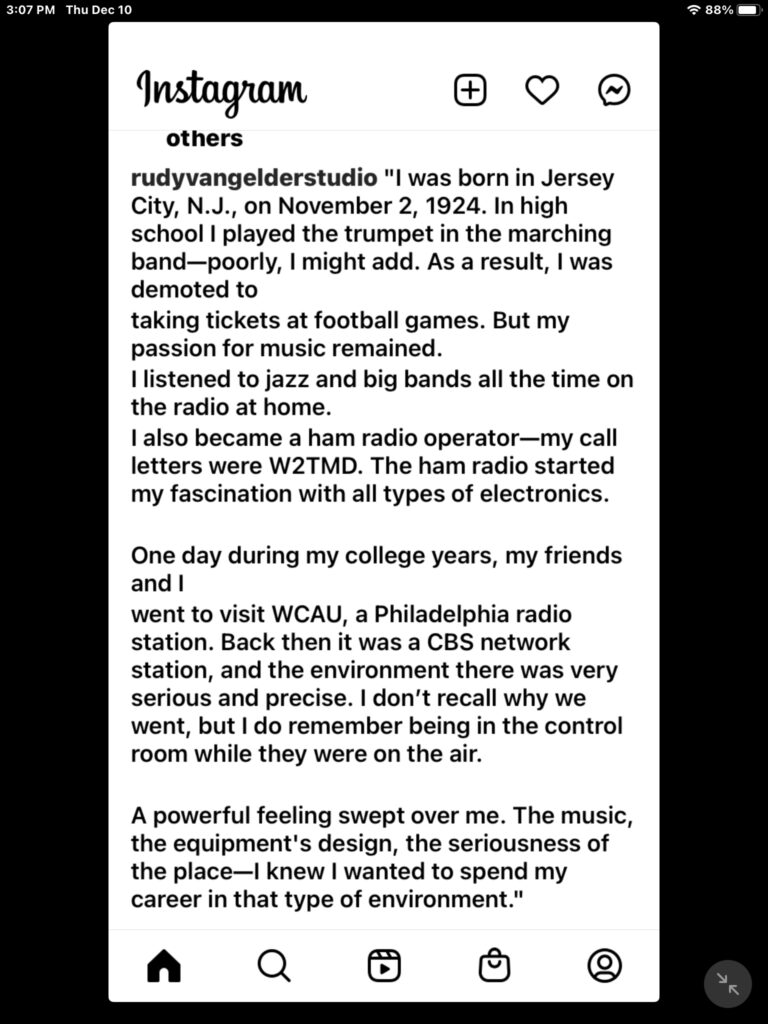

Rudy Van Gelder was born on November 2, 1924 in Jersey City. He trained as an optometrist, but always loved sound and as a youth had developed an interest in microphones and electronics.

Here’s an Instagram screen-grab of a post by rudyvangelerstudio:

While he was still a practicing optometrist his parents built a home in Hackensack, NJ. He asked if their plans could include a recording studio.

They said yes and he recorded there until the completion of Van Gelder Studios in nearby Englewood Cliffs in July 1959. There were over 367 recording sessions in Hackensack alone.

Recording Engineer Rudy Van Gelder

Jazz

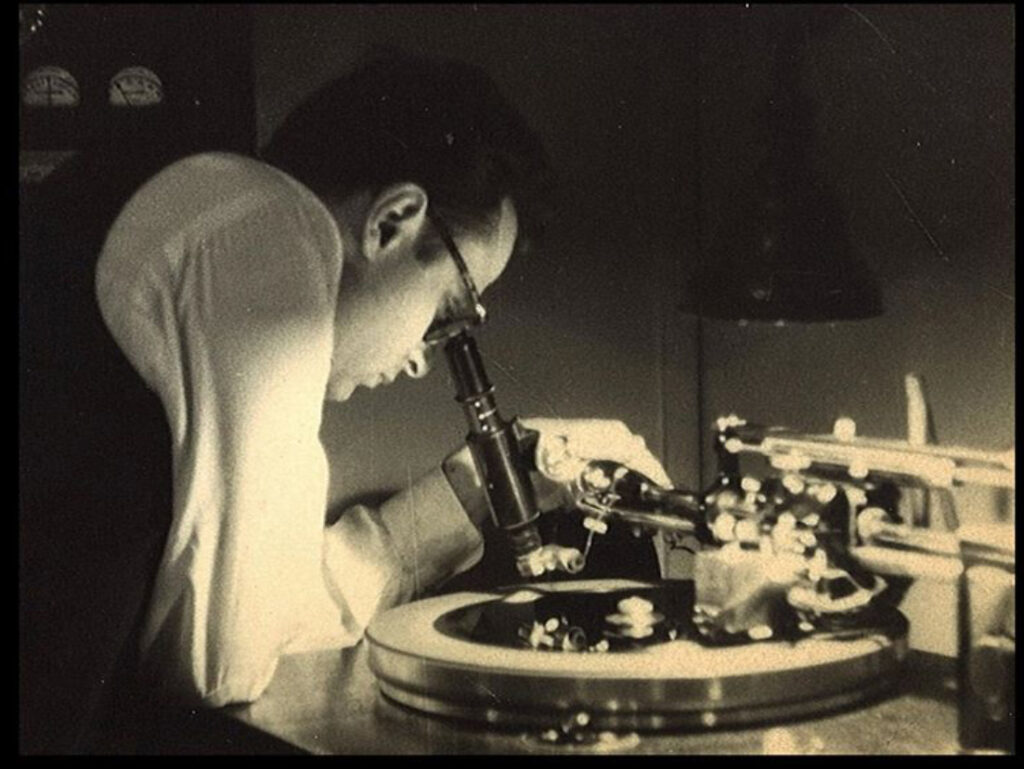

Van Gelder was extremely attentive to the recording process. Some might said to a fault. And jazz was his domain. According to a 2012 article in JazzWax by Benny Goldson, “Rudy’s many accomplishments and contributions include inventing techniques for capturing sound naturally in an age when most recording equipment wasn’t up to the job, the creative placement of microphones, the early use of magnetic recording tape, a recording process that wasn’t easily duplicated by other engineers, and turning his name into a brand that has been synonymous with jazz itself ever since.”

And Van Gelder’s answer to Goldson’s first question may be all we need to know: “Some people think I’m a producer. I’m not. I’m a recording engineer. I don’t hire the musicians nor do I come up with concepts for albums or how well musicians are playing. I’m there to capture the music at the time it’s being created. This requires me to concentrate on the technical aspects of the recordings, which means the equipment and how the finished product is going to sound.”

Recording Engineer Rudy Van Gelder

Englewood Cliffs, NJ

After those years of part-time recording in Hackensack, Van Gelder decided to become a full time audio engineer in 1959. He constructed the now famous Van Gelder Studios (also his home): 445 Sylvan Avenue, Englewood Cliffs, New Jersey.

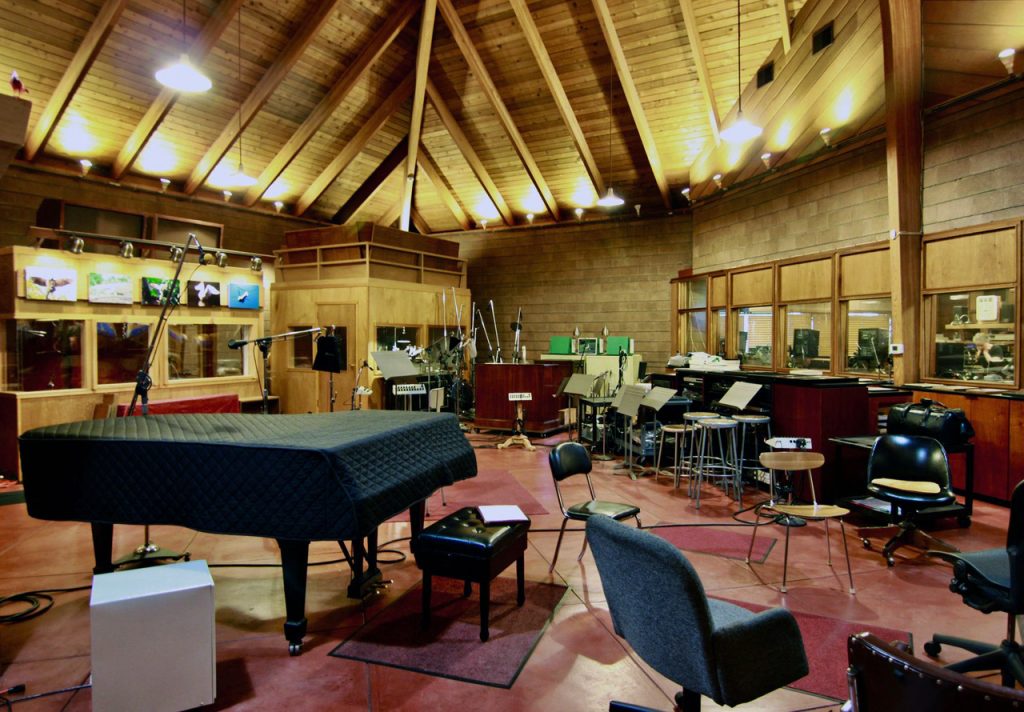

The Usonian movement in architecture inspired Van Gelder’s vision of the studio. Both utilitarian (simple building materials) and affordable (keep in mind that Van Gelder was still a practicing optometrist to make ends meet). Frank Lloyd Wright was a proponent of the Usonian approach and Van Gelder found David Henken, also a proponent of the vision, to design the building.

Van Gelder, in his way, described it simply as, “The five walls allow the sound to move up into the rafters and back down without being trapped or muffled.”

In 2001, Ira Gitler wrote in a Jazz Time article: I opened my notes to The Space Book by Booker Ervin with: In the high-domed, wooden-beamed, brick-tiled, spare modernity of Rudy Van Gelder’s studio, one can get a feeling akin to religion.” Rudy didn’t say anything at the time bot in 2000 he straightened me out. “The wooden beams are in the roof,” he explained, “and the walls are not tiles but masonry.” Duly noted, but “it remains a non-sectarian non-organized religion temple of music in which the sound and the spirit can seemingly soar unimpeded.”

Recording Engineer Rudy Van Gelder

Perform, don’t touch

Van Gelder was fastidious in his approach–only he could touch equipment; he always wore gloves when touching equipment; he set up mics; no food; no smoking.

He rarely spoke specifically about the various techniques he learned to get “his sound.”

To musicians, not generally known for being fastidiousness, Van Gelder’s approach might sound too Puritan, a recipe for failure, but they, loved the Van Gelder sound and flocked to Englewood Cliffs.

Between the studio’s opening on July 20, 1959 to its closing on February 28, 2011, Van Gelder had over 1300 recording sessions.

He also was always looking for audio advances. While he may have started with aluminum lacquer-coated discs that were then reproduced on 78-rpm singles, he was one of the first audio engineers to switch to recording tape because of its flexibility and lower cost.

Today’s audiophiles might be shocked (and disappointed) to hear that in 1989 he went digital. Why?

“If you just listen once to what it can do within my environment here, you would never want to record analogue again – and I didn’t,” he said to the trade press at the time. (Telegraph article)

Recording Engineer Rudy Van Gelder

Credits

One can only imagine the months of music Rudy Van Gelder recorded and left behind. If All Music’s credit list is complete, then it is an astounding legacy.

Some would say that of the thousands of hours, you only need to listen to one album: John Coltrane’s A Love Supreme.

When asked, Van Gelder said, “The most momentous recording of the 1960s for me was John Coltrane’s A Love Supreme. It was hypnotic. It was exciting. It was different.“

Yet it took nearly 40 years for him to realize that. “I came to that realization only when I remastered the album for its digital reissue in 2002. You have to understand, I was busy making sure that the work was recorded perfectly. It wasn’t until I was working on updating the original master that I listened intently to the music.”

Rudy Van Gelder died on August 25, 2016 in Englewood Cliffs, NJ. He died in his home–down the hall from his studio. (NPR obituary)