South Vietnam Leadership

France was, of course, a long time American ally so it should come as no surprise that the United States supported France’s colonial policies.

French Indochina

Vietnam was one of France’s colonies. Under its rule, Bảo Đại, a member of the Nguyễn dynasty, had succeeded as emperor in 1926 and was a figurehead ruler.

Japan ruled the area under Đại during World War II.

In 1944, optimistic of Allied success in the Pacific, President Roosevelt wrote that “Indo-China should not go back to France…France has had the country…one hundred years, and the people are worse off than they were at the beginning.”

South Vietnam Leadership

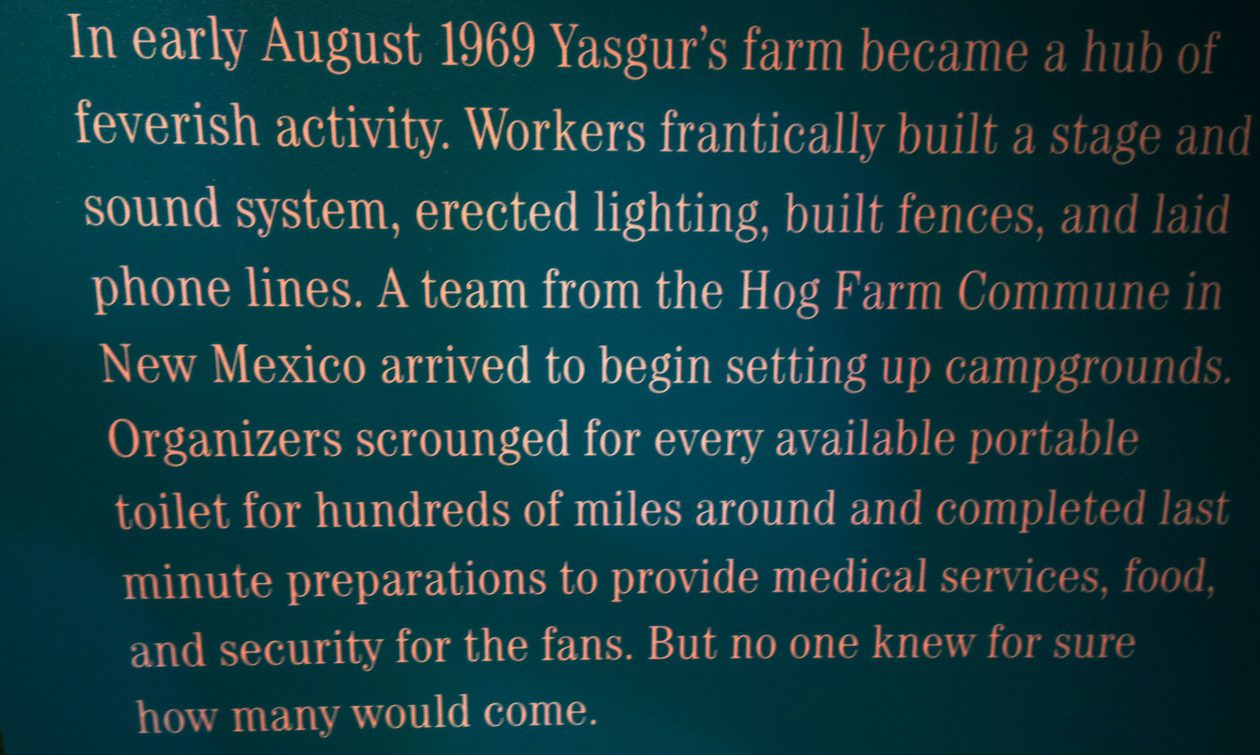

August Revolution

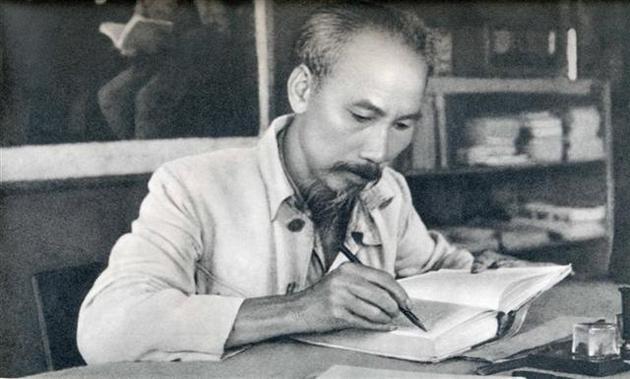

On August 16, 1945, two days after Japan indicated a willingness to surrender, Vietnamese leader Ho Chi Minh issued an appeal to the Vietnamese people urging them to seize control of their country before Allied troops arrived in Indochina.

The uprising succeeded in overthrowing Bảo Đại and gaining control both Hanoi and Saigon. The uprising became known as the “August Revolution.”

September 2, 1945: Japan formally surrendered and Ho Chi Minh and the Viet Minh proclaimed the Democratic Republic of Vietnam. He paraphrased the U.S. Declaration of Independence: “All men are born equal: the Creator has given us inviolable rights, life, liberty, and happiness!” and was cheered by an enormous crowd gathered in Hanoi.

The Allied powers disagreed and the British first then the French attempted to gain control of the region.

South Vietnam Leadership

Bảo Đại returns

On March 8, 1949, France recognized an ‘independent’ State of Vietnam, with emperor Bảo Đại returning as head of government and on February 7, 1950 the United States recognized Vietnam under the leadership of Đại, not Ho Chi Minh.

On March 8, 1949, France recognized an ‘independent’ State of Vietnam, with emperor Bảo Đại returning as head of government and on February 7, 1950 the United States recognized Vietnam under the leadership of Đại, not Ho Chi Minh.

The USSR and China had recognized Ho Chi Minh’s authority.

That same year, the United States announced military and financial support for the pro-French government in Vietnam.

South Vietnam Leadership

Indochina War

War broke out between the French and north Vietnam.

April 7, 1954: President Dwight D. Eisenhower coined one of the most famous Cold War phrases when he suggests the fall of French Indochina to the communists could create a “domino” effect in Southeast Asia.

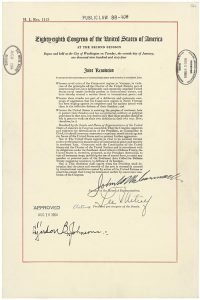

April 26 – July 20, 1954: the Geneva Conference held. It was intended to settle Indochina’s political and territorial issues following World War II.

It was during the conference, on May 7, that Vietnamese forces occupied the French command post at Dien Bien Phu and the French commander ordered his troops to cease fire.

The battle had lasted 55 days. Three thousand French troops were killed, 8,000 wounded. The Viet Minh suffered much worse, with 8,000 dead and 12,000 wounded, but the Vietnamese victory shattered France’s resolve to carry on the war.

South Vietnam Leadership

Geneva Conference

Three successor states were created from the partition of French Indochina: the Kingdom of Cambodia, the Kingdom of Laos, and the Democratic Republic of Vietnam, the state led by Ho Chi Minh and Viet Minh.

Three successor states were created from the partition of French Indochina: the Kingdom of Cambodia, the Kingdom of Laos, and the Democratic Republic of Vietnam, the state led by Ho Chi Minh and Viet Minh.

The State of Vietnam was reduced to the southern part of Vietnam. The division of Vietnam was intended to be temporary, with elections planned by July 1956 to reunify the country.

On June 4, 1954, French and Vietnamese officials signed treaties in Paris.

South Vietnam Leadership

Ngô Đình Diệm

July 7, 1954: with Bảo Đại still emperor, Ngô Đình Diệm became Prime Minister and established his new government in South Vietnam with a cabinet of 18 people.

July 7, 1954: with Bảo Đại still emperor, Ngô Đình Diệm became Prime Minister and established his new government in South Vietnam with a cabinet of 18 people.

July 21, 1954: the Geneva Accords concluded the Geneva Conference with the division of Vietnam into two countries along the 17th parallel of latitude with elections scheduled for 1956.

October 24, 1954: President Eisenhower wrote to Diệm and promised direct assistance to his government. Eisenhower made it clear to Diệm that U.S. aid to his government during Vietnam’s “hour of trial” was contingent upon his assurances of the “standards of performance [he] would be able to maintain in the event such aid were supplied.”

Eisenhower called for land reform and a reduction of government corruption. Diệm agreed to the “needed reforms” stipulated as a precondition for receiving aid, but he never actually followed through on his promises. Ultimately his refusal to make any substantial changes to meet the needs of the people led to extreme civil unrest and eventually a coup by dissident South Vietnamese generals in which Diệm and his brother were murdered.

Battle of Saigon

April 27, 1955: The Battle of Saigon began.

President Eisenhower had previously decided to cease US support for Prime Minister Ngô Đình Diệm and let him be ousted, but on April 28, 1955, US Secretary of State John Foster Dulles told the National Security Council to hold off on allowing the ousting of Diệm pending the outcome of the Battle of Saigon.

It was a month-long fight between the Vietnamese National Army (VNA) of the State of Vietnam (later to become the Army of the Republic of Vietnam) and the private army of the Bình Xuyên organised crime syndicate.

At the time, the Bình Xuyên was licensed with controlling the national police by Emperor Bảo Đại. Prime Minister Ngô Đình Diệm issued an ultimatum for them to surrender and come under state control.

The VNA largely crushed the Bình Xuyên within a week.

Fighting was mostly concentrated in the inner city Chinese business district of Cholon. The densely crowded area saw some 500 – 1000 deaths and up to 20,000 civilians made homeless in the cross-fire.

In the end, the Bình Xuyên were decisively defeated, their army disbanded and their vice operations collapsed.

South Vietnam Leadership

National Referendum

July 7, 1955: on the first anniversary of his installation as Prime Minister, Diệm announced that a national referendum would be held to determine the future of the country.

July 16, 1955: Diệm announced his intention to not take part in the reunification elections negotiated in : “We will not be tied down by the [Geneva] treaty that was signed against the wishes of the Vietnamese people.”

October 6, 1955: Ngô Đình Diệm announced the referendum would be held on 23 October The election was open to men and women aged 18 or over, and the government arranged to have a polling station set up for every 1,000 registered voters.

Bảo Đại, who had spent much of his time in France and advocated a monarchy. Diệm ran on a republican platform.

October 23, 1955: Ngo Dinh Diệm reportedly received 98.2% of the votes, a difficult winning percentage to believe which was further supported by the fact that the total number of votes for exceeded the number of registered voters by over 380,000.

South Vietnam Leadership

President Ngô Đình Diệm

Republic of Vietnam

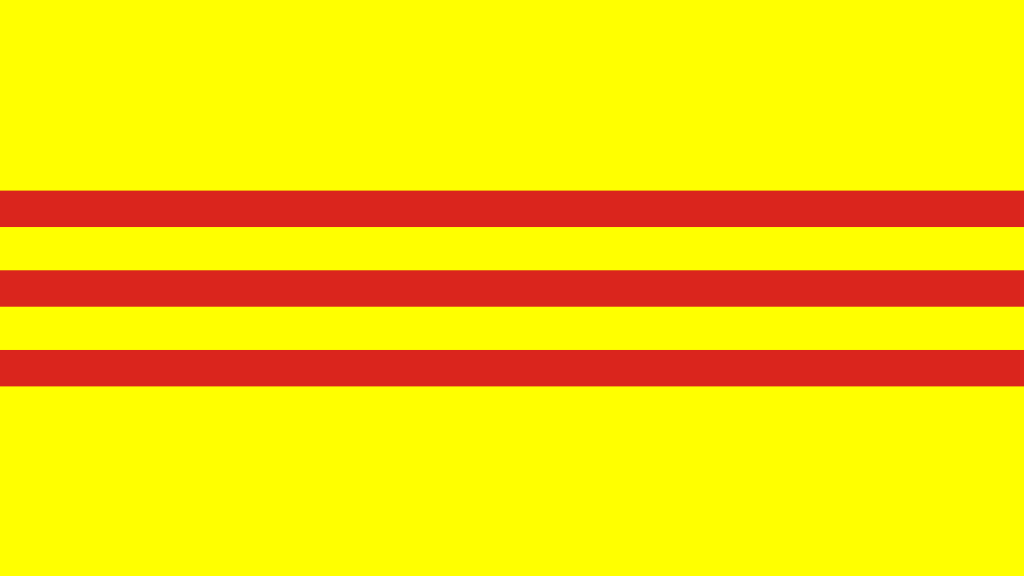

October 26, 1955: Ngô Đình Diệm proclaimed the formation of the Republic of Vietnam, with himself as its first President.

In 1957, Diệm embarked on a two-week visit to the United States. He flew from Hawaii on President Dwight Eisenhower’s private plane, Columbine III. President Eisenhower personally greeted Diệm at the National Airport where Diệm received full military honors including a 21-gun salute.

On May 9, Diệm addressed a Joint Meeting, presided over by Speaker of the House Sam Rayburn of Texas and Vice President Richard M. Nixon of California. Diệm expressed gratitude to the United States for “moral and material aid.”

Five Year Miracle

July 7, 1959: on the fifth anniversary of Diệm’s coming to power, a NY Times editorial stated: a five year miracle has been carried out. Vietnam is free and becoming stronger in defense of its freedom and ours. There is reason today to salute president Ngo Dihn Diệm.”

South Vietnam Leadership

Attempted overthrows

November 11, 1960: Lieutenant Colonel Vương Văn Đông and Colonel Nguyễn Chánh Thi of the Airborne Division of the Army of the Republic of Vietnam led a failed coup attempt against Diệm .

February 27, 1962: Second Lieutenant Nguyễn Văn Cử and First Lieutenant Phạm Phú Quốc targeted Independence Palace, Diệm and his immediate family’s official residence.

The attempt failed. Cử escaped to Cambodia, but Quốc was arrested and imprisoned.

South Vietnam Leadership

Troubled waters

December 2, 1962: following a trip to Vietnam at President John F. Kennedy’s request, Senate Majority Leader Mike Mansfield (D-Montana) became the first U.S. official to refuse to make an optimistic public comment on the progress of the war.

Originally a supporter of Diệm, Mansfield changed his opinion of the situation after his visit. He claimed that the $2 billion the United States had poured into Vietnam during the previous seven years had accomplished nothing. He placed blame squarely on the Diệm regime for its failure to share power and win support from the South Vietnamese people.

He suggested that Americans, despite being motivated by a sincere desire to stop the spread of communism, had simply taken the place formerly occupied by the French colonial power in the minds of many Vietnamese. Mansfield’s change of opinion surprised and irritated Kennedy.

South Vietnam Leadership

Diệm cracks down

Flags banned

May 6, 1963: President Diệm issued a proclamation banning the flying of all religious flags throughout the country. He said he found their use “disorderly,” but his actual aim was to keep the flags from becoming symbols of resistance to his regime.

Huế Phật Đản shootings

May 8, 1963: the deaths of nine unarmed Buddhist civilians in the Huế at the hands of Roman Catholic fundamentalist government Ngô Đình Diệm’s army and security forces.

The army and police fired guns and launched grenades into a crowd of Buddhists who had been protesting against the government ban on the flying of the Buddhist flag on the day of Phật Đản, which commemorates the birth of Gautama Buddha.

Diệm’s denial of governmental responsibility for the incident—he instead blamed the Việt Cộng—added to discontent among the Buddhist majority.

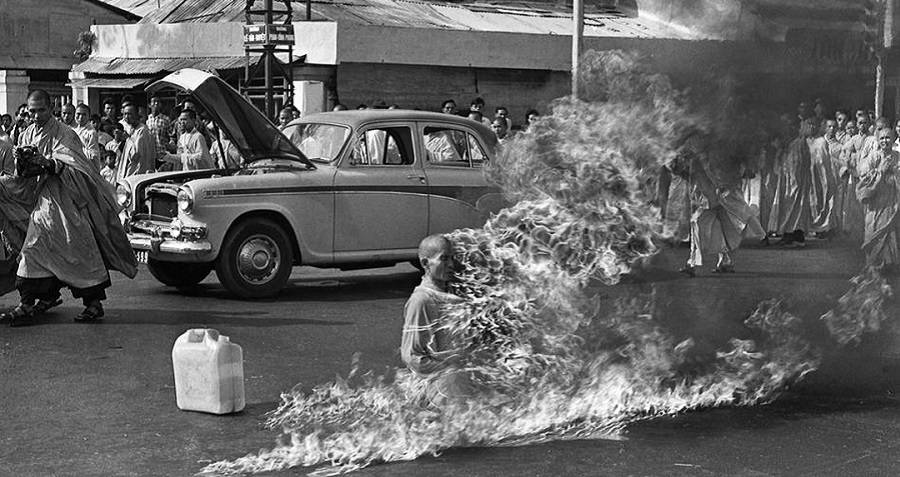

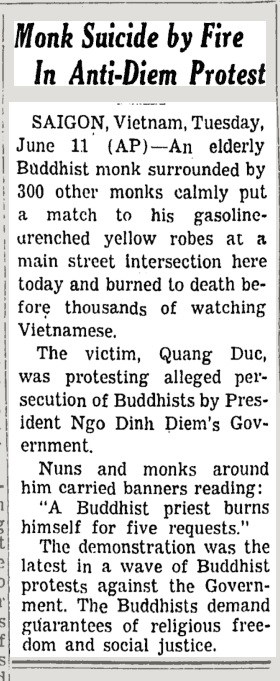

Quang Duc

June 11, 1963: Buddhist monk Quang Duc publicly burned himself to death in a plea for President Ngo Dinh Diệm to show “charity and compassion” to all religions. Diệm remained stubborn despite continued Buddhist protests and repeated U.S. requests to liberalize his government’s policies.

More Buddhist monks immolated themselves during ensuing weeks. Madame Nhu, the president’s sister-in-law, referred to the burnings as “barbecues” and offered to supply matches.

June 16, 1963: President Diệm and Buddhist negotiations issued a joint communique meant to defuse the religious conflict: the ban on religious flags would be eased and the Hue incident of May 8 would be fully investigated.

South Vietnam Leadership

Diệm cuts phone lines

August 21, 1963: after Diệm promised outgoing US Ambassador Frederick Nolting to take no further repressive steps against the Buddhists and before the new American ambassador, Henry Cabot Lodge, arrived, Diệm and his brother Ngô Đình Nhu (Diệm’s chief political adviser) ordered that phone lines of all the senor American officials in Saigon be cut and then sent out hundreds of their Special Forces into pagodas of Saigon, Hue, and other cities.

The Special Forces rounded up and took away more than fourteen hundred monks and nuns, students, and ordinary citizens. Martial law was imposed, public meetings forbidden, and troops were authorized to shoot anyone found on the streets after nine o’clock.

South Vietnam Leadership

Warnings

August 24, 1963: assistant secretary of state for Far Eastern affairs, Roger Hilsman Jr, took it upon himself to draft a cable to new US Ambassador to Vietnam, Henry Cabot Lodge, stating that the US government could no longer tolerate the situation in which “power lies in Nhu’s hands.”

Lodge was to tell key military leaders that “we must face the possibility that Diệm himself cannot be preserved.” Kennedy on vacation and preoccupied with other domestic matters, approved the cable.

South Vietnam’s military leaders backed off from a coup.

South Vietnam Leadership

Military Revolutionary Council

November 1, 1963: South Vietnamese general Dương Văn Minh, acting with the support of the CIA, launched a military coup which removed Diệm from power.

November 2, 1963: Ngo Dinh Diệm and brother Ngô Đình Nhu surrendered, but were murdered. ‘

The Military Revolutionary Council, as it called itself, dissolved Diệm’s rubber stamp National Assembly and the constitution of 1956. They vowed support free elections, unhindered political opposition, freedom of the press, freedom of religion, an end to discrimination, and that the purpose of the coup was to bolster the fight against the Vietcong.

November 5, 1964: South Vietnam’s five generals decided on a two-tier government structure with a military committee overseen by Dương Văn Minh presiding over a regular cabinet that would be predominantly civilian with Nguyễn Ngọc Thơ as Prime Minister, , Minister of Economy, and Minister of Finance.

November 8, 1964: US Government recognized the new South Vietnam government.

South Vietnam Leadership

Coups

General Nguyễn Khánh

January 30, 1964: General Nguyễn Khánh ousted General Dương Văn Minh from the leadership without firing a shot. It came less than three months after Minh’s junta had come to power in a bloody coup against then President Ngô Đình Diệm.

January 30, 1964: General Nguyễn Khánh ousted General Dương Văn Minh from the leadership without firing a shot. It came less than three months after Minh’s junta had come to power in a bloody coup against then President Ngô Đình Diệm.

The coup was bloodless and took less than a few hours—after power had been seized Minh’s aide and bodyguard, Major Nguyễn Văn Nhung was arrested and summarily executed.

The New York Times reported, ““The bloodless coup d’état executed by the short, partly bald general apparently took Saigon by surprise.”

Attempted Coup Deux

Before dawn on September 13, 1964, a coup attempt headed by Generals Lâm Văn Phát and Dương Văn Đức threatened the ruling military junta of South Vietnam, led by General Nguyễn Khánh.

Generals Lâm Văn Phát and Dương Văn Đức sent dissident units into the capital Saigon. They captured various key points and announced over national radio the overthrow of the incumbent regime. With the help of the Americans, Khánh was able to rally support and the coup collapsed the next morning without any casualties.

Rearrangement coup

December 19, 1964: a coup took place before dawn. The ruling military junta of South Vietnam led by General Nguyễn Khánh dissolved the High National Council (HNC) and arrested some of its members. The HNC was an un-elected legislative-style civilian advisory body they had created at the request of the United States.

Military coup

February 19, 1965: some units of the Army of the Republic of Vietnam commanded by General Lâm Văn Phát and Colonel Phạm Ngọc Thảo launched a coup against General Nguyễn Khánh.

Their aim was to install General Trần Thiện Khiêm, a Khánh rival who had been sent to Washington D.C. as Ambassador to the United States to prevent him from seizing power.

The attempted coup reached a stalemate, and although the trio did not take power, a group of officers led by General Nguyễn Chánh Thi and Air Marshal Nguyễn Cao Kỳ, and hostile to both the plot and to Khánh himself, were able to force a leadership change and take control themselves with the support of American officials, who had lost confidence in Khánh.

Phan Huy Quát was appointed Prime Minister.

Phan Huy Quát was appointed Prime Minister.

South Vietnam Leadership

General Nguyễn Khánh

February 20, 1965: Nguyễn Khánh was able to get troops to take over from the insurgents without any resistance. Meanwhile, Air Vice Marshal Nguyen Cao Ky met with the dissident officers and agreed to their demand for the dismissal of Khanh.

South Vietnam Leadership

Generals

February 21, 1965: the Armed Forces Council dismissed Gen Nguyễn Khánh as chairman and as commander of the armed forces. General Lâm Văn Phát replaced him.

February 22, 1965: General Nguyễn Khánh announced that he had accepted the council’s decision. Although he was hastily given the title of ambassador at large, General Khánh would never again play a significant role in his country’s future.

Phan Huy Quát resigns

June 14, 1965: mounting Roman Catholic opposition to South Vietnamese Premier Phan Huy Quát’s government led him to resign.

National Leadership Committee

On the same day, a military triumvirate headed by Army General Nguyễn Văn Thiệu took over and expanded to a 10-man National Leadership Committee.

The Committee decreed the death penalty for Viet Cong (aka, National Liberation Front) terrorists, corrupt officials, speculators, and black marketeers.

Catholics warned the military against favoring the Buddhists, who asked for an appointment of civilians to the new cabinet.

Nguyễn Cao Kỳ

On June 19, 1965, Nguyễn Cao Kỳ was appointed prime minister by a special joint meeting of military leaders following the voluntary resignation of civilian president Phan Khắc Sửu and Prime Minister Quát,

On June 19, 1965, Nguyễn Cao Kỳ was appointed prime minister by a special joint meeting of military leaders following the voluntary resignation of civilian president Phan Khắc Sửu and Prime Minister Quát,

South Vietnam Leadership

Buddhist Struggle

May 15, 1966: on Premier Ky’s orders, without notifying Thieu or the U.S., a pro-government military force arrived in Da Nang to take control of the city from the Buddhist Struggle movement protesting against the government and American influence.

May 18, 1966: U.S. Marines faced off against pro-Buddhist ARVN soldiers at a bridge near Da Nang. A few shots were exchanged and the ARVN soldiers attempted to blow up the bridge. General Lewis William Walt, the commander of the U.S. Marines in South Vietnam, was present and directed the Marines to secure the bridge.

May 24, 1966: the government of South Vietnam regained full control of Da Nang from the pro-Buddhist Struggle Movement. In the fighting, approximately 150 South Vietnamese soldiers were killed. 23 Americans were wounded.

South Vietnam Leadership

President Nguyễn Văn Thiệu

September 3, 1967: Nguyen Van Thieu, the candidate of the armed forces, won a four-year term as President of South Vietnam.

He was re-elected on October 2, 1971 without opposition in what was widely viewed as a rigged election.

He remained in power until April 21, 1975 when he resigned, condemning the United States for its lack of promised support following the US military withdrawal.

He will die in 2001.