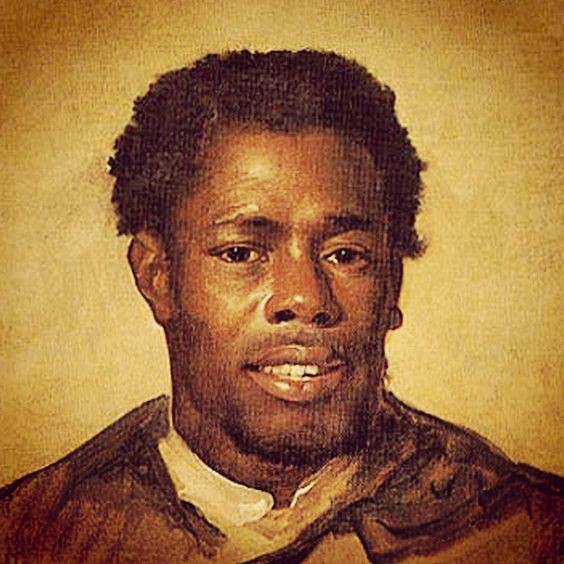

Nat Turner Slave Revolt 1831

From 1831–1862: The Underground Railroad Approximately 75,000 slaves escape to the North and to freedom via the Underground Railroad, a system in which free African American and white “conductors,” abolitionists and sympathizers help guide and shelter the escapees.

Birth and education

October 2, 1800: Nat Turner was born on the plantation of Benjamin Turner in Southampton County, Virginia, the week before Gabriel Prosser (see Aug 30) was hanged after a failed slave insurrection in Richmond, Virginia.

Nat Turner’s mother was enslaved woman named Nancy, who was captured from West Africa. His father, presumed to be a slave named Abraham, ran away from the Southampton, Virginia, plantation when Nat was about ten years old

Benjamin Turner allowed Nat Turner to be instructed in reading, writing, and religion.

Nat Turner Slave Revolt 1831

First vision

While still a young child, Nat was overheard describing events that had happened before he was born. This, along with his keen intelligence, and other signs marked him in the eyes of his people as a prophet.

Nat was given as a gift, along with his mother and grandmother, to Benjamin’s son Samuel around 1809, and formally willed in 1810.

In 1821, Turner ran away from Samuel, but returned after thirty days because of a vision in which the Spirit had told him to “return to the service of my earthly master.”

Nat Turner Slave Revolt 1831

Second Vision

By 1822, Samuel had died, and his widow, Elizabeth Turner, oversaw Nat until she married Thomas Moore, who took formal ownership of Nat in 1823.

According to a National Geographic article, “After Elizabeth’s death, Moore married Sally Francis, who became a widow and then married Joseph Travis, Nat’s last master, although Sally’s 10-year-old son, Putnam, was legally Nat’s owner.”

In 1825: Nat Turner had a second vision. He saw lights in the sky and prayed to find out what they meant. Then “… while laboring in the field, I discovered drops of blood on the corn, as though it were dew from heaven, and I communicated it to many, both white and black, in the neighborhood; and then I found on the leaves in the woods hieroglyphic characters and numbers, with the forms of men in different attitudes, portrayed in blood, and representing the figures I had seen before in the heavens.”

Nat Turner Slave Revolt 1831

Third Vision

May 12, 1828: Turner “…heard a loud noise in the heavens, and the Spirit instantly appeared to me and said the Serpent was loosened, and Christ had laid down the yoke he had borne for the sins of men, and that I should take it on and fight against the Serpent, for the time was fast approaching when the first should be last and the last should be first… And by signs in the heavens that it would make known to me when I should commence the great work, and until the first sign appeared I should conceal it from the knowledge of men; and on the appearance of the sign… I should arise and prepare myself and slay my enemies with their own weapons.”

By 1830, Southampton County was home to 6,573 whites, 1,745 free blacks, and 7,756 enslaved African Americans.

It was in 1830 that Turner was moved to the home of Joseph Travis with his official owner being the young child Putnum Moore. Turner described Travis as a kind master, against whom he had no complaints. The Travis plantation was lived 411 acres and had 17 slaves working his property in 1830.

Records show that Nat married an enslaved woman named Cherry who lived on a neighboring plantation, and they had at least one child, a son named Reddick. Nat would have to obtain a pass from his masters to visit his family.

Records show that he was outspoken in his beliefs that blacks should be free, and that freedom would be theirs one day; an opinion for which he was whipped in 1828.

Nat Turner Slave Revolt 1831

Signs from the heavens

February 1831: there was an eclipse of the sun. Turner took this to be the sign he had been promised and confided his plan to the four men he trusted the most, Hark Moore, Henry Porter, Nelson Edwards, Sam Francis, Will Francis, and Jack Reese . They decided to hold an insurrection on July 4 and began planning a strategy. However, they had to postpone action because Turner became ill.

August 13, 1831: there was an atmospheric disturbance in which the sun appeared bluish-green. Turner interpreted this as the final sign.

Nat Turner Slave Revolt 1831

Revolt

August 21, 1831: Turner, Moore, Porter, Edwards, Sam Francis, Will Francis, and Reese met in the woods to eat a dinner and make their plans.

At 2:00 AM they launched the rebellion by entering the Travis household, where they killed the entire family as they lay sleeping, save for a small infant. They moved from one farm to the next, killing all slave-owning whites they found. As they progressed through Southampton county, other slaves joined in the rebellion.

They continued on, from house to house, killing all of the white people they encountered. Turner’s force eventually consisted of more than 40 slaves, most on horseback.

August 22, 1831: Turner decided to march toward Jerusalem, the closest town. By then word of the rebellion had gotten out to the whites; confronted by a group of militia, the rebels scattered, and Turner’s force became disorganized. After spending the night near some slave cabins, Turner and his men attempted to attack another house, but were repulsed. One slave was killed and many escaped, including Turner.

Nat Turner Slave Revolt 1831

Escape

In the end, the rebels had stabbed, shot and clubbed at least 55 white people to death.Turner escaped and remained free for nearly two months.

In those two months though, the militia and white vigilantes instituted a reign of terror over slaves in the region. Hundreds of blacks were killed. White Virginians panicked over fears of a larger slave revolt and soon instituted more restrictive laws regulating slave life.

Nat Turner Slave Revolt 1831

Capture

August 30, 1831: The Richmond Enquirer published a description of the rebels’ “murderous career” that likened them to “a parcel of blood-thirsty wolves rushing down from the Alps; or rather like a former incursion of the Indians upon the white settlements.” The lesson gleaned by the writer of the article from the case of Turner, “who had been taught to read and write, and permitted to go about preaching,” was that “No black man ought to be permitted to turn a Preacher through the country.”

Credit was given to “many of the slaves whom gratitude had bound to their masters, that thy had manifested the grestest alacrity in detecting and apprehending many of the brigands.”

According to the article, General Broadnax, the militia commander of Greensville County, was “convinced, from various sources” of the “entire ignorance on the subject of all the slaves in the counties around Southampton, among whom he has never known more pefect order and quiet to prevail.” [full text of article]

Nat Turner Slave Revolt 1831

Harriet Ann Jacobs

Harriet Ann Jacobs, born into slavery in North Carolina in 1813, eventually escaped to the North, where she wrote a narrative about her ordeal of slavery.

In Chapter Twelve of Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl, Written by Herself, Jacobs describes the harassment of blacks in Edenton, North Carolina, following the rebellion.

Her “Fear of Insurrection” begins with a statement that captured the irony of white society’s fear: NOT far from this time Nat Turner’s insurrection broke out; and the news threw our town into great commotion. Strange that they should be alarmed when their slaves were so “contented and happy”! But so it was. [full text]

October 30, 1831: Turner captured and imprisoned in the Southampton County Jail, where he was interviewed by Thomas R. Gray, a Southern physician. Out of that interview came his now famous “Confession.”

Convinced that “the great day of judgement was at hand,” and that he “should commence the great work,” Turner took the eclipse of the sun to mean that “I should arise and prepare myself, and slay my enemies with their own weapons.”

Gray described Turner as being extremely intelligent but a fanatic. He went on to say: “The calm, deliberate composure with which he spoke of his late deeds and intentions, the expression of his fiend-like face when excited by enthusiasm; still bearing the stains of the blood of helpless innocence about him; clothed with rags and covered with chains, yet daring to raise his manacled hands to heaven; with a spirit soaring above the attributes of man, I looked on him and my blood curdled in my veins.”

Nat Turner Slave Revolt 1831

Trial and execution

November 5, 1831: Nat Turner was tried in the Southampton County Court and sentenced to execution. (BH, NT, & SR, see Nov 10)

November 10, 1831: Nat Turner hung. He was buried the following day.

No grave marker exists for Nat Turner, nor for his fellow soldiers. The rebels were caught, tried, and executed in different places, and their scattered remains lie under unmarked soil.

The November 14, 1831, Norfolk Herald reported that: “He betrayed no emotion, but appeared to be utterly reckless in the awful fate that awaited him and even hurried his executioner in the performance of his duty! Precisely at 12 o’clock he was launched into eternity.”

In total, the state executed 55 people, banished many more, and acquitted a few. The state reimbursed the slaveholders for their slaves. But in the hysterical climate that followed the rebellion, close to 200 black people, many of whom had nothing to do with the rebellion, were murdered by white mobs. In addition, slaves as far away as North Carolina were accused of having a connection with the insurrection, and were subsequently tried and executed.

The state legislature of Virginia considered abolishing slavery, but in a close vote decided to retain slavery and to support a repressive policy against black people, slave and free.

The basic information for this blog entry came from Brotherly Love, a PBS article.