United States Pledge Allegiance

Divided Allegiances

It is always a good idea to look back at our Pledge of Allegiance’s history.

It might seem that we’ve always had one, but like most social icons, the United States had no allegiance to the flag for more than a century and we’ve only had a government sanctioned one for less than a century.

Here’s some of that timeline.

United States Pledge Allegiance

19th century genesis

October 12, 1892: during Columbus Day observances organized to coincide with the opening of the World’s Columbian Exposition in Chicago, Illinois, the pledge of allegiance was recited for the first time.

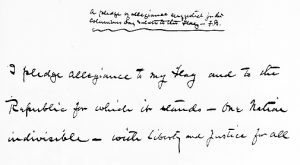

Francis Bellamy [Smithsonian article], a Christian Socialist, had initiated the movement for such a statement and having flags in all classrooms. His pledge was: I pledge allegiance to my Flag and the Republic for which it stands, one nation indivisible, with liberty and justice for all.

United States Pledge Allegiance

An adjustment

In 1923: the called for the words “my Flag” to be changed to “the Flag of the United States,” so that new immigrants would not confuse loyalties between their birth countries and the United States. The words “of America” were added a year later.

United States Pledge Allegiance

Patriotism on display

May 3, 1937: as the rest of the world headed toward World War II, a patriot fervor swept the U.S., as it had before, during and after World War I.

Walter Gobitas

One expression of that movement involved state laws requiring public school students to salute the flag each morning. The Jehovah’s Witnesses, however, regarded saluting the flag as an expression of a commitment to a secular authority and unfaithfulness to God.

One expression of that movement involved state laws requiring public school students to salute the flag each morning. The Jehovah’s Witnesses, however, regarded saluting the flag as an expression of a commitment to a secular authority and unfaithfulness to God.

As a result, some families had their children refuse to participate in the compulsory salute. On this day, Walter Gobitas (the family name was misspelled in the court case) sued the Minersville, Pennsylvania, School Board, in a case that ended up in the Supreme Court: Minersville School District v. Gobitis.

June 3, 1940: Minersville School District v. Gobitis, was a decision by the US Supreme Court involving the religious rights of public school students under the First Amendment to the US Constitution.

The Court ruled that public schools could compel students—in this case, Jehovah’s Witnesses—to salute the American Flag and recite the Pledge of Allegiance despite the students’ religious objections to these practices.

United States Pledge Allegiance

Pledge of Allegiance official

June 22, 1942: the US Congress officially recognized the Pledge for the first time [Gilder Lehrman Institute article] , in the following form: I pledge allegiance to the flag of the United States of America, and to the Republic for which it stands, one Nation indivisible, with liberty and justice for all.

June 22, 1942: the US Congress officially recognized the Pledge for the first time [Gilder Lehrman Institute article] , in the following form: I pledge allegiance to the flag of the United States of America, and to the Republic for which it stands, one Nation indivisible, with liberty and justice for all.

During the 1920s and 1930s, Italian fascists and Nazis adopted salutes which were similar in form, resulting in controversy over the use of the Bellamy salute in the United States.

December 22, 1942: Congress amended the Flag code to replace the Bellamy salute with the the hand-over-heart salute. The Bellamy salute had been the salute described by Francis Bellamy to accompany the American Pledge of Allegiance, which he had authored.

United States Pledge Allegiance

FREE SPEECH?

June 14, 1943: West Virginia State Board of Education v. Barnette, the US Supreme Court held that the Free Speech Clause of the First Amendment to the Constitution protected students from being forced to salute the American flag and say the Pledge of Allegiance in school. It was a significant court victory won by Jehovah’s Witnesses, whose religion forbade them from saluting or pledging to symbols, including symbols of political institutions. However, the Court did not address the effect the compelled salutation and recital ruling had upon their particular religious beliefs, but instead ruled that the state did not have the power to compel speech in that manner for anyone.

Barnette overruled the June 3, 1940 decision (Minersville School District v. Gobitis) which also involved the children of Jehovah’s Witnesses.

United States Pledge Allegiance

“under God”

February 12, 1948: Louis A. Bowman, an attorney from Illinois, was the first to initiate the addition of “under God” to the Pledge. He was Chaplain of the Illinois Society of the Sons of the American Revolution. At a meeting on February 12, 1948, Lincoln’s Birthday, he led the Society in swearing the Pledge with two words added, “under God.”

He stated that the words came from Lincoln’s Gettysburg Address. Though not all manuscript versions of the Gettysburg Address contain the words “under God”, all the reporters’ transcripts of the speech as delivered do, as perhaps Lincoln may have deviated from his prepared text and inserted the phrase when he said “that the nation shall, under God, have a new birth of freedom.”

United States Pledge Allegiance

Knights of Columbus

April 30, 1951: the Knights of Columbus, the world’s largest Catholic fraternal service organization, had begun to include the words “under God” in the Pledge of Allegiance. On this date in New York City the Knights of Columbus Board of Directors adopted a resolution to amend the text of their Pledge of Allegiance at the opening of each of the meetings of the 800 Fourth Degree Assemblies of the Knights of Columbus by addition of the words “under God” after the words “one nation.”

Over the next two years, the idea spread throughout Knights of Columbus organizations nationwide.

August 21, 1952: the Supreme Council of the Knights of Columbus at its annual meeting adopted a resolution urging that the change be made universal and copies of this resolution were sent to the President, the Vice President (as Presiding Officer of the Senate) and the Speaker of the House of Representatives.

United States Pledge Allegiance

President Eisenhower baptized

February 1, 1953: President Eisenhower was baptized, confirmed, and became a communicant in the Presbyterian church in a single ceremony.

United States Pledge Allegiance

George MacPherson Docherty

It had become a tradition that some American presidents honored Lincoln’s birthday by attending services at the church Lincoln attended in Washington, DC, [the New York Avenue Presbyterian Church] and sitting in Lincoln’s pew on the Sunday nearest February 12.

It had become a tradition that some American presidents honored Lincoln’s birthday by attending services at the church Lincoln attended in Washington, DC, [the New York Avenue Presbyterian Church] and sitting in Lincoln’s pew on the Sunday nearest February 12.

On February 7, 1954, with President Eisenhower sitting in Lincoln’s pew, the church’s pastor, George MacPherson Docherty [Washington Post obit], delivered a sermon based on the Gettysburg Address titled “A New Birth of Freedom.”

He argued that the nation’s might lay not in arms but its spirit and higher purpose. He noted that the Pledge’s sentiments could be those of any nation, that “there was something missing in the pledge, and that which was missing was the characteristic and definitive factor in the American way of life.” He cited Lincoln’s words “under God” as defining words that set the United States apart from other nations.

President Eisenhower, baptized a Presbyterian the previous February, responded enthusiastically to Docherty in a conversation following the service. (Christian Perspective article on Eisenhower)

United States Pledge Allegiance

“under God” gets Presidential support

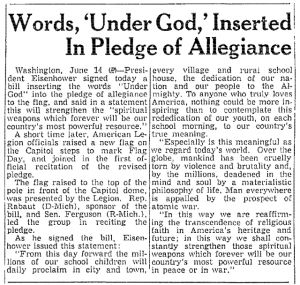

February 8, 1954: Eisenhower acted on Rev Doucherty’s suggestion and Rep. Charles Oakman (R-Mich.), introduced a bill to that effect.

June 14, 1954: President Eisenhower signed the bill into law on Flag Day, stating, “From this day forward, the millions of our school children will daily proclaim in every city and town, every village and rural school house, the dedication of our nation and our people to the Almighty. … In this way we are reaffirming the transcendence of religious faith in America’s heritage and future; in this way we shall constantly strengthen those spiritual weapons which forever will be our country’s most powerful resource, in peace or in war.”

United States Pledge Allegiance

Stay or leave

March 4, 1969: the New York City Corporation Council upheld the petition of Dorothy Lynn, a 17-year-old Queens, NY high school student to leave her classroom during the Pledge of Allegiance.

Lynn said that she did not believe in God or that everyone was granted liberty and justice. (NYT article)

United States Pledge Allegiance

Sit or stand?

October 31, 1969: Mary Frain and Susan Keller, two 12-year-old 7th grade girls in Brooklyn went to court to assert their right to remain seated in class while other students recited the Pledge of Allegiance.

Referring to the Vietnam War, one of the students said she refused to recite the pledge because she doesn’t believe that “the actions of this country at this time warrant my respect.”

The school had suspended the seventh graders four weeks earlier in what the school board’s attorney described as a simple matter of school discipline and not one of First Amendment law. Allowing the girls to remain seated, he claimed, would be “disruptive.”

New York Civil Liberties Union lawyers represented the girls. The NYCLU cited the Supreme Court case of West Virginia v. Barnette, decided of June 14, 1943, in which the Court upheld the right of Jehovah’s Witness’s children not to salute the American flag as required by their school.

On December 10, Judge Orrin G Judd, enjoined the city school system from telling student that they must leave the classrooms if they do not want to stand and recite the Pledge.

Judd said the students had a constitutinal right to remain seated until the school could prove that by sitting through the Pledge the students had “materially infringed” the rights of other students or had caused disruption. (NYT article)

United States Pledge Allegiance

New Jersey

August 16, 1977: a Federal District Court overturned a New Jersey state law requiring all public school students in New Jersey to at least stand at attention during the pledge of allegiance to the American flag. [NYT article]

Judge H. Curtis Meanor ruled that the standing mandated by the State Education Law illegally compelled “symbolic speech” and violated students’ First Amendment rights of freedom of expression and speech.

The New Jersey statute stipulated that the pledge be recited and a flag salute rendered by all children in public schools, except for the children of foreign diplomats or for youngsters with “conscientious scruples” against the acts.

But the law required that the exempt pupils “be required to show full respect to the flag while the pledge is being given merely by standing at attention.” Judge Meanor objected to the “mandatory language” of that section of the law.

United States Pledge Allegiance

Under or not under God?

June 27, 2002: a federal appeals court declared that the Pledge of Allegiance was unconstitutional because the phrase ”one nation under God” violated the separation of church and state. [NY Times article]

A three-member panel of the United States Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit ruled that the pledge, as it exists in federal law, could not be recited in schools because it violates the First Amendment’s prohibition against a state endorsement of religion. In addition, the ruling turned on the phrase ”under God” which Congress added in 1954 to one of the most hallowed patriotic traditions in the nation.

From a constitutional standpoint, those two words, Judge Alfred T. Goodwin wrote in the 2-to-1 decision, were just as objectionable as a statement that ”we are a nation ‘under Jesus,’ a nation ‘under Vishnu,’ a nation ‘under Zeus,’ or a nation ‘under no god,’ because none of these professions can be neutral with respect to religion.’

August 9, 2002: the U.S. Justice Department filed an appeal of the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals’ ruling in the Newdow vs. U.S. Congress case in which the court struck down the addition of the phrase “under God” to the Pledge of Allegiance as unconstitutional.

February 28, 2003: the 9th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals, which ruled that the addition of “under God” to the The Pledge of Allegiance was unconstitutional, refused to reconsider its ruling, saying it would be wrong to allow public outrage to influence its decisions.

March 4, 2003: the US Senate voted 94-0 that it “strongly” disapproved of the 9th Circuit Court of Appeals decision not to reconsider its ruling that the addition of the phase “under God” to the The Pledge of Allegiance was unconstitutional.

United States Pledge Allegiance

Bush administration appeal

April 30, 2003: the Bush administration appealed to the Supreme Court to preserve the phrase “under God” in the The Pledge of Allegiance recited by school children. Solicitor General Theodore Olson said that “Whatever else the (Constitution’s) establishment clause may prohibit, this court’s precedents make clear that it does not forbid the government from officially acknowledging the religious heritage, foundation and character of this nation,” and that the Court could strike down the 9th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals ruling in Newdow vs. United States without even bothering to hear arguments.

June 14, 2003: in the case of Newdow v. U.S. Congress Oyez article[], the US Supreme Court overturned a Ninth Circuit Court decision that struck the addition of “under God” to the Pledge of Allegiance. The 8-0 ruling was reached on a technicality: that Michael Newdow doesn’t have standing to bring the case in the first place. (Constitution Society dot com article)

United States Pledge Allegiance

And the beat goes on…

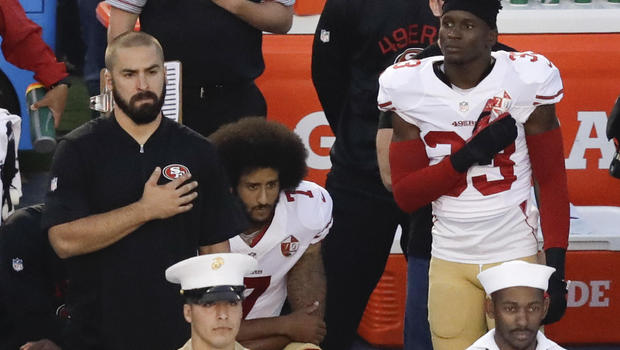

October 7, 2017: a federal lawsuit charged that Windfern High School suspended India Landry, a 17-year-old Houston student, after refusing to stand for the daily Pledge of Allegiance.

Landry said that she had sat for the Pledge hundreds of times at Windfern High School without incident,however, Principal Martha Strother removed her after Landry declined to stand for the Pledge.

According to the lawsuit, school administrators had “recently been whipped into a frenzy” by the controversy caused by NFL players kneeling for the national anthem.

The lawsuit also charged that India was told after she was expelled that “if your mom does not get here in five minutes the police are coming.”

Washington Post article on the Pledge’s history.