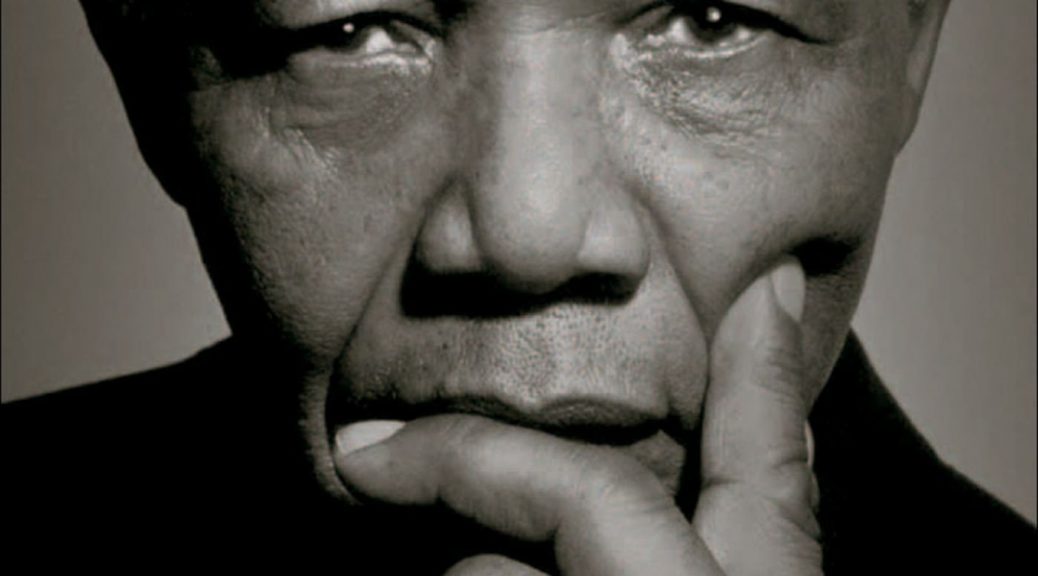

Rolihlahla Nelson Mandela

July 18, 1918 – December 5, 2013

The following timeline is not intended on being a fully complete list of all the major events in Mandela’s life, but hopefully there are enough listed to give the reader a fuller appreciation of Mandela’s heroic life including the advent and end of apartheid.

Rolihlahla Nelson Mandela

Madiba clan

Rolihlahla Mandela was born into the Madiba clan in the village of Mvezo, in the Eastern Cape, on 18 July 1918. His mother was Nonqaphi Nosekeni and his father was Nkosi Mphakanyiswa Gadla Mandela, principal counselor to the Acting King of the Thembu people, Jongintaba Dalindyebo.

His primary school teacher gave Mandela the Christian name Nelson, as was the custom.

According to the Nelson Mandela dot org site:

He completed his Junior Certificate at Clarkebury Boarding Institute and went on to Healdtown, a Wesleyan secondary school of some repute, where he matriculated.

Mandela began his studies for a Bachelor of Arts degree at the University College of Fort Hare but did not complete the degree there as he was expelled for joining in a student protest.

On his return to the Great Place at Mqhekezweni the King was furious and said if he didn’t return to Fort Hare he would arrange wives for him and his cousin Justice. They ran away to Johannesburg instead, arriving there in 1941. There he worked as a mine security officer and after meeting Walter Sisulu, an estate agent, he was introduced to Lazer Sidelsky. He then did his articles through a firm of attorneys – Witkin, Eidelman and Sidelsky.

He completed his BA through the University of South Africa and went back to Fort Hare for his graduation in 1943.

Rolihlahla Nelson Mandela

ANC Youth League

On April 2, 1944, Mandela and other activists formed the African National Congress Youth League after becoming disenchanted with the cautious approach of the older members of the African National Congress (The ANC had been formed on January 8, 1912)

The youth league’s formation marked the shift of the congress to a mass movement. But its manifesto, so charged with pan-African nationalism, offended some non-black sympathizers.

Rolihlahla Nelson Mandela

Apartheid

In 1948: the National Party took power in South Africa and set out to construct apartheid, a system of strict racial segregation and white domination.

Mandela began studying for an LLB, but he left the university without graduating. He had earned a two-year diploma in law which allowed him and Oliver Tambo, in August 1952, to open South Africa’s first black law practice.

Rolihlahla Nelson Mandela

Arrest

December 5, 1956: South African authorities arrested Nelson Mandela at his home and charged him with treason, along with 155 others who had called for a nonracial state in South Africa.

March 21, 1960: police fired on a demonstration in Sharpeville, killing 69 people and wounding 181. After the shooting, the South African government banned black political groups and gatherings and arrested thousands. The African National Congress was among the banned groups. Its members went underground and began to plan a campaign of direct attacks on the apartheid government.

The 1956 Treason Trial ended on March 29, 1961. Mandela and his co-defendants were acquitted of treason. Fearing he would be arrested again, Mandela went underground.

Rolihlahla Nelson Mandela

Umkhonto we Sizwe

December 16, 1961: Mandela and other A.N.C. leaders formed a military wing called Umkhonto we Sizwe, or Spear of the Nation. Mandela became the first commander in chief of the guerrilla army. He trained to fight, work to obtain weapons for the group, and came to be known as the Black Pimpernel, but he would never see combat.

January 11, 1962, using the adopted name David Motsamayi, Mandela secretly left South Africa. He traveled around Africa and visited England to gain support for the armed struggle. He received military training in Morocco and Ethiopia and returned to South Africa in July 1962.

August 5, 1962: Mandela was arrested after his returning to South Africa. He was convicted of leaving the country illegally and ofincitement to strike, and sentenced to five years in prison.

November 6, 1962: the United Nations General Assembly passed Resolution 1761, which condemned Apartheid in South Africa and called on member-nations to boycott the country. The Resolution also set up a Special Committee against Apartheid.

Rolihlahla Nelson Mandela

Rivonia Trial

July 11, 1963: police raided a farm in Rivonia, outside Johannesburg, where the African National Congress had set up its headquarters. They find documents outlining the group’s plan for guerrilla warfare. Using the evidence found on the farm, the government charges Mandela and eight co-defendants with sabotage and conspiracy to overthrow the government. The ensuing trial, which became known as the Rivonia trial, established Mandela’s central role in the struggle against apartheid.

October 9, 1963 Mandela joined 10 others on trial for sabotage.

April 20, 1964: Mandela delivered his famous “I am prepared to die” speech while on trial.

[exerpt] “Africans want to be paid a living wage. Africans want to perform work which they are capable of doing, and not work which the Government declares them to be capable of. We want to be allowed to live where we obtain work, and not be endorsed out of an area because we were not born there. We want to be allowed and not to be obliged to live in rented houses which we can never call our own. We want to be part of the general population, and not confined to living in our ghettoes. African men want to have their wives and children to live with them where they work, and not to be forced into an unnatural existence in men’s hostels. Our women want to be with their men folk and not to be left permanently widowed in the reserves. We want to be allowed out after eleven o’clock at night and not to be confined to our rooms like little children. We want to be allowed to travel in our own country and to seek work where we want to, where we want to and not where the Labour Bureau tells us to. We want a just share in the whole of South Africa; we want security and a stake in society.

Above all, My Lord, we want equal political rights, because without them our disabilities will be permanent. I know this sounds revolutionary to the whites in this country, because the majority of voters will be Africans. This makes the white man fear democracy.

But this fear cannot be allowed to stand in the way of the only solution which will guarantee racial harmony and freedom for all. It is not true that the enfranchisement of all will result in racial domination. Political division, based on colour, is entirely artificial and, when it disappears, so will the domination of one colour group by another. The ANC has spent half a century fighting against racialism. When it triumphs as it certainly must, it will not change that policy.

This then is what the ANC is fighting. Our struggle is a truly national one. It is a struggle of the African people, inspired by our own suffering and our own experience. It is a struggle for the right to live.

During my lifetime I have dedicated my life to this struggle of the African people. I have fought against white domination, and I have fought against black domination. I have cherished the ideal of a democratic and free society in which all persons will live together in harmony and with equal opportunities. It is an ideal for which I hope to live for and to see realised. But, My Lord, if it needs be, it is an ideal for which I am prepared to die.” [full text]

Rolihlahla Nelson Mandela

Convictions

On June 11 Mandela and seven others [Walter Sisulu, Ahmed Kathrada, Govan Mbeki, Raymond Mhlaba, Denis Goldberg, Elias Motsoaledi and Andrew Mlangeni] were convicted and on June 12 they were sentenced to life in prison.

Mandela was sent to Robben Island prison, seven miles off the coast of Cape Town. He would spend the next 18 years there.

Rolihlahla Nelson Mandela

Continued protests

August 18, 1964: the International Olympic Committee barred South Africa from participating in the Summer Olympics due to the country’s Apartheid policy. The nation would not be reinstated until 1992.

June 16, 1976: tens of thousands of students take to the streets of Soweto to oppose the use of Afrikaans as the language of instruction in black schools. The police fire on the protesters, setting off months of violence that will leave more than 570 people dead. The uprising is considered a turning point in the history of black resistance to apartheid.

November 9, 1976: The United Nations General Assembly approved 10 resolutions condemning apartheid in South Africa.

April 27, 1977: Anti-apartheid riots in Soweto, South Africa.

Rolihlahla Nelson Mandela

Steve Biko

August 18, 1977: In South Africa police arrested Steve Biko [headed the Black Consciousness Movement and was the country’s best known political dissident] and Peter Jones at Grahamstown.

August 31, 1977: Ian Smith, espousing racial segregation, won the Rhodesian general election with 80% of overwhelmingly white electorate’s vote.

September 11, 1977: a guard found Steve Biko semiconscious and foaming at the mouth. A doctor ordered him transported to a prison hospital in Pretoria.

September 12, 1977: Steven Biko died while in police custody. Police had driven him naked in a truck 700 miles to Pretoria where he died in a prison cell.

Peter Gabriel released the song Biko in 1980. Its success continued to keep the violence of South Africa’s apartheid system in the minds of many.

Rolihlahla Nelson Mandela

Mandela transferred

March 28, 1982: Mandela and four other A.N.C. leaders were transferred from Robben Island to Pollsmoor Prison in the suburbs of Cape Town. While many believe the move was intended to lessen the influence of the famous prisoners, government officials later say they wanted a way to open a discreet line of communication with the men.

Rolihlahla Nelson Mandela

Sun City

In 1985, activist and performer Steven Van Zandt and record producer Arthur Baker organized a protest against apartheid in South Africa.

Sun City was a place where the South African government had allowed entertainment that was banned in most of the country.

Van Zandt wrote a song called Sun City and invited many recording artists to participate in its recording. Some of those who participated were: including Kool DJ Herc, Grandmaster Melle Mel, Ruben Blades, Bob Dylan, Pat Benatar, Herbie Hancock, Ringo Starr and his son Zak Starkey, Lou Reed, Run–D.M.C., Peter Gabriel, Bob Geldof, Clarence Clemons, David Ruffin, Eddie Kendricks, Darlene Love, Bobby Womack, Afrika Bambaataa, Kurtis Blow, The Fat Boys, Jackson Browne, Daryl Hannah, Peter Wolf, Bono, George Clinton, Keith Richards, Ronnie Wood, Bonnie Raitt, Hall & Oates, Jimmy Cliff, Big Youth, Michael Monroe, Stiv Bators, Peter Garrett, Ron Carter, Ray Barretto, Gil Scott-Heron, Nona Hendryx, Kashif, Lotti Golden, Lakshminarayana Shankar and Joey Ramone.

They vowed never to perform at Sun City, because to do so would in their minds seem to be an acceptance of apartheid.

Rolihlahla Nelson Mandela

Bishop Tutu/PW Botha

October 16, 1984: South African activist Bishop Desmond Tutu awarded Nobel Peace Prize.

February 10, 1985: South Africa’s president, P. W. Botha, offered to free Mandela if he renounced violence. Mandela refused, saying the government must first dismantle apartheid.

Rolihlahla Nelson Mandela

More killings

March 21, 1985: police in Langa, South Africa, opened fire on blacks marching to mark the 25th anniversary of the Sharpeville shootings, killing at least 21 demonstrators.

April 15, 1985: South Africa ended its ban on interracial marriages.

July 20, 1985: P. W. Botha declares a state of emergency in 36 magisterial districts of South Africa amid growing civil unrest in black townships.

State of Emergency

June 12, 1986: the South African government declared a nationwide state of emergency, granting itself sweeping powers, including authorization for the police to use force against protesters and to impose curfews. The decree bans the promotion of unlawful strikes, boycotts and protests and puts tight restrictions on the press. More than 1,000 activists are detained.

September 7, 1986: Desmond Tutu became the first Black Anglican Church bishop in South Africa.

Reagan veto/override

September 26, 1986: President Reagan vetoed the Comprehensive Anti-Apartheid Act. The law would have imposed sanctions against South Africa and stated five preconditions for lifting the sanctions that would essentially end the system of apartheid.

September 29, 1986: the House of Representatives voted to overrides the President Reagan’s veto of the Comprehensive Anti-Apartheid Act.

October 2, 1986: the US Senate overrode President Reagan’s veto of the Comprehensive Anti-Apartheid Act and the bill became a law.

Rolihlahla Nelson Mandela

Free Nelson Mandela Concert

June 11, 1988: the biggest charity rock concert since Live Aid three years earlier took place at London’s Wembley Stadium, to denounce South African apartheid. Among the performers were Sting, Stevie Wonder, Bryan Adams, George Michael, Whitney Houston and Dire Straits. Half the money raised went towards anti-apartheid activities in Britain, the rest was donated to children’s charities in southern Africa.

12 August 1988: Mandela was hospitalized with tuberculosis. After more than three months in two hospitals he was transferred on December 7, 1988 to the Victor Verster Prison Farm, about 50 miles from Cape Town.

The South African government said he would not have to return to Pollsmoor Prison.

Easing

July 5, 1989: Mandela met informally with Mr. Botha at the presidential office in Cape Town. It is the first publicly acknowledged meeting between Mr. Mandela and a government official outside prison, and leads to speculation that he will soon be released. [NYT article]

August 15, 1989: F. W. de Klerk is sworn in as acting president of South Africa, replacing Mr. Botha. Saying the country is about to enter an era of change, Mr. de Klerk reaffirmed an earlier promise to phase out white rule.

October 15, 1989: the government freed eight of the country’s most prominent political prisoners, including Walter Sisulu, 77, a mentor to Mr. Mandela and his close friend, in a gesture that was widely seen as a trial run for Mandela’s release.

December 13, 1989: South African President F.W. de Klerk met for the first time with imprisoned African National Congress leader Nelson Mandela, at de Klerk’s office in Cape Town.

February 2, 1990: South Africa President F.W. de Klerk lifted the ban on the A.N.C. and several other political organizations, and lifted many of the restrictions put in place when the state of emergency was declared four years earlier. He promised that Mandela would be released shortly.

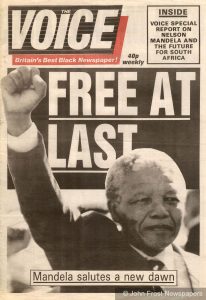

Release

February 11, 1990: Nelson Mandela, 71, released from Victor Verster Prison, near Cape Town, South Africa, after 27 years behind bars. [NYT article}

June 10, 1990: the Central Intelligence Agency played an important role in the arrest in 1962 of Nelson Mandela. The intelligence service, using an agent inside the African National Congress, provided South African security officials with precise information about Mr. Mandela’s activities that enabled the police to arrest him. The report quoted an unidentified retired official who said that a senior C.I.A. officer told him shortly after Mr. Mandela’s arrest: ”We have turned Mandela over to the South African Security branch. We gave them every detail, what he would be wearing, the time of day, just where he would be.”

August 7, 1990: The A.N.C. announced that it ordered the immediate suspension of its guerrilla campaign against apartheid, which started in the early 1960s. While the war between the A.N.C. and the government had operated on a low level for years, the announcement was significant because it gave de Klerk political ammunition to use against the right-wing opposition to negotiations.

October 15, 1990: South Africa’s Separate Amenities Act, which had barred blacks from public facilities for decades, was scrapped.

June 17, 1991: South Africa repealed the Population Registration Act. Since its passage in 1950, the Act had required every South African to be racially classified at birth. These classifications, in turn, would determined the child’s social and political rights for the rest of his or her life in South Africa.

December 20, 1991: negotiations begin to prepare an interim constitution based on full political equality. de Klerk and Mandela traded recriminations, with de Klerk criticizing Mr. Mandela for not disbanding the A.N.C.’s inactive guerrilla operation and Mandela saying that the president “has very little idea of what democracy is.”

Rolihlahla Nelson Mandela

More killing

June 17, 1992: a mob descended on the black township of Boipatong, killing more than 40 people with guns, knives and axes. The A.N.C. contended that Zulu men and white police officers were responsible for the violence. (see June 23). The two sides do not return to negotiations until September.

June 23, 1992: the African National Congress announced that it was withdrawing from talks on the political future of South Africa until the white-controlled Government took steps to restore the trust shattered by the Boipatong massacre. The 90-member executive committee of the congress led by Nelson Mandela said it was halting the peace process, which seemed just a month ago to have brought South Africa to the brink of majority rule, because of what it called a systematic Government campaign to subvert democracy through violence.

Rolihlahla Nelson Mandela

Paul Simon

January 11, 1992: Paul Simon was the first major artist to tour South Africa after the end of the cultural boycott. [NYT article]

April 10. 1993: Chris Hani, a popular black leader of the South African Communist Party, was shot and killed by a white man. At least seven people were killed in clashes over the following days. Mandela appeared on national television and called for calm, urging a stronger commitment to negotiations, a contrast to the A.N.C.’s confrontational reaction to the massacre in Boipatong the year before.

Rolihlahla Nelson Mandela

Nobel Peace Prize

October 15, 1993: Mandela and FW de Klerk share the Nobel Peace Prize. The two men accept the award with the strained grace that characterized their relationship, and Mandela declined to repeat his much-quoted assessment of Mr. de Klerk as a man of integrity.

January 3, 1994: more than 7 million people received South African citizenship that had previously been denied under Apartheid policies.

April 27, 1994: general voting opened in the first election in South African history that included black participation. Despite months of violence leading up to the vote, not a single person was reported killed in election-related violence. When the voting concluded on April 29, the A.N.C. had won more than 62 percent of the vote, earning 252 of the 400 seats in Parliament’s National Assembly. Voters choes Mandela as president without opposition.

Rolihlahla Nelson Mandela

Presidency

May 10, 1994: Mandela sworn in as president of South Africa, making a speech of shared patriotism that summons South Africans’ communal exhilaration in their land and their relief at being freed from the world’s disapproval.

June 24, 1995: South Africa’s national rugby team, the Springboks, won the World Cup final. The team had been banned from international competition until 1992, and was long seen as a symbol of oppression by many black South Africans. Mr. Mandela’s call for blacks to support the team is hailed as a masterly move toward racial reconciliation. He congratulated the team while wearing a green Springboks jersey, in a stadium full of cheering white rugby fans.

November 1, 1995: South Africans voted in their first all-race local government elections, completing the destruction of the apartheid system.

Rolihlahla Nelson Mandela

Recriminations

October 30, 1996: saying many of Eugene de Kock’s actions had been cruel, calculated and without any sympathy for the victims Judge Willem van der Merwe sentenced the former head of a South African police assassination squad to two life sentences and more than 200 years in jail. (see below, January 30, 2015)

December 10, 1996: Mandela signed into law a new democratic constitution, completing the country’s transition from white-minority rule to a non-racial democracy.

January 28, 1997: four apartheid-era police officers, appearing before the Truth and Reconciliation Commission, admit to the 1977 killing of Stephen Biko, a leader of the South African “Black consciousness” movement.

Rolihlahla Nelson Mandela

Peaceful transfer

June 16, 1999: Thabo Mbeki inaugurated as Mandela’s successor as president of South Africa after another electoral victory for the A.N.C. After five years with Mr. Mandela at the helm, the country still faced serious problems of poverty and crime, but it had made the transition to democracy while maintaining widespread respect for the law and avoiding political revenge killings.

June 1, 2004: Mandela says he would severely reduce his public activities so he could spend his remaining years resting and writing. A month shy of 86, he was increasingly frail and had trouble walking.

December 8, 2012: Mandela was hospitalized for nearly 19 days, being treated for pneumonia and having an operation for gallstones.

Rolihlahla Nelson Mandela

Mandela’s death

December 5, 2013: Mandela, who led the emancipation of South Africa from white minority rule and served as his country’s first black president, becoming an international emblem of dignity and forbearance, died. He was 95. [NYT editorial]

January 30, 2015: the South African government granted parole to Eugene de Kock, a death squad leader for the apartheid state, after two decades in jail. “In the interest of nation building and reconciliation, I have decided to place Mr. de Kock on parole,” said Justice Minister Michael Masutha.

The Nelson Mandela Foundation, a non-profit organization continues to promote Mandela’s vision of freedom and equality for all.