1964 Gulf Tonkin Ghost Attack

August 4, 1964

Robert McNamara from the documentary, “The Fog of War.”

1964 Gulf Tonkin Ghost Attack

August 2, 1964

It had been 254 days since President Kennedy’s assassination in Dallas, Texas.

254.

The number of days that President Lyndon B Johnson was president. November 3, Election Day, 93 days away. He had signed the landmark Civil Rights Act of 1962 exactly a month earlier.

Vietnam was a mosquito; not a tiger.

Military intelligence had suggested that there might be North Vietnamese military action in the Gulf of Tonkin. The Captain of the destroyer USS Mattox, Captain, John J. Herrick, was on alert.

On this date, Secretary of Defense Robert McNamara reported to President Johnson that North Vietnamese torpedo boats had attacked the Maddox.

1964 Gulf Tonkin Ghost Attack

What happened

Three North Vietnamese patrol boats had engaged the Maddox. Herrick ordered the crew to commence firing as the North Vietnamese boats came within 10,000 yards of the ship.

10,000 yards is over 5 miles.

Herrick also called in air support from a nearby air craft carrier, the USS Ticonderoga. The North Vietnamese boats each fired torpedoes at the Maddox, but two missed and the third failed to explode. U.S. gunfire hit one of the North Vietnamese boats. US jets strafed them.

1964 Gulf Tonkin Ghost Attack

The Result

Maddox gunners sunk one of the boats and two were crippled. One bullet hit the Maddox and there were no U.S. casualties.

The US took no further action, but warned the Vietnamese to cease such attacks.

Gulf Tonkin Ghost Attack

August 4, 1964

Two days later around 8 PM, the Maddox and the USS C. Turner Joy, both in the Gulf of Tonkin, intercepted North Vietnamese radio messages. Captain Herrick got the “impression” that Communist patrol boats are planning an attack against the American ships. He again called for the support of the USS Ticonderoga.

Neither the pilots nor the ship crews saw any enemy craft. However, about 10 p.m. sonar operators reported torpedoes approaching. The destroyers maneuvered to avoid the torpedoes and began to fire at the North Vietnamese patrol boats. The encounter lasted about two hours. U.S. officers reported sinking two, or possibly three of the North Vietnamese boats, but no one was sure.

Herrick communicated his doubts to his superiors and urged a “thorough reconnaissance in daylight.” Shortly thereafter, he informed Admiral U. S. Grant Sharp, commander of the Pacific Fleet, that the blips on the radar scope were apparently “freak weather effects” while the report of torpedoes in the water were probably due to “overeager” radar operators.

1964 Gulf Tonkin Ghost Attack

President Johnson’s reaction

Convinced that a second attack had occurred, President Johnson, ordered the Joint Chiefs of Staff to select targets for possible retaliatory air strikes. At a National Security Council meeting, Secretary of Defense Robert McNamara, Secretary of State Dean Rusk, and McGeorge Bundy, Special Assistant to the President for National Security Affairs, recommended the ordering of reprisal attacks to the president.

Though cautious at first, eventually Johnson gave the order to execute the reprisal, code-named Pierce Arrow. The President then met with 16 Congressional leaders to inform them of the second unprovoked attack and that he had ordered reprisal attacks. He also told them he planned to ask for a Congressional resolution to support his actions.

At 11:20 p.m., Admiral Sharp informed McNamara that the aircraft were on their way to the targets and at 11:26, President Johnson appeared on national television and announced that the reprisal raids were underway in response to unprovoked attacks on U.S. warships. He assured the viewing audience that, “We still seek no wider war.”

1964 Gulf Tonkin Ghost Attack

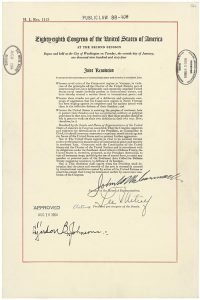

Gulf of Tonkin Resolution

On August 7, the House of Representatives unanimously (416 – 0) and the Senate overwhelmingly (88 – 2) approved the so-called Gulf of Tonkin Resolution. Its title read, “”To promote the maintenance of international peace and security in southeast Asia.” [text]

President Johnson signed the resolution on August 10.

In 1964, there were approximately 23,300 troops in Vietnam.

By 1965 that number was 184,300.

There were 536,000 U.S. troops in Vietnam in 1968.