Feminist Abolitionist Myrtilla Miner

March 4, 1815 – December 17, 1864

Feminist Abolitionist Myrtilla Miner

Early life

On March 4, 1815, Myrtilla Miner was born in North Brookfield, NY. She was one of 13 children in a poor farming family. Often in ill health, she found comfort in reading and studying. With great persistence and financial difficulty, she graduated from the Young Ladies Domestic Seminary with a teaching degree. She taught in Rochester, NY and Providence, R.I., before accepting a position in the late 1840s in Whitesville, Mississippi.

There she taught at a school for the daughters of plantation owners. There, too, she saw the desperate conditions under which slaves lived. An educator to her core, she naively asked the slave owners if she could start a school to teach the slave girls to read. Myrtilla Miner did not realize that such a benefit was against the law.

Sickness sent her back home to New York, but in 1851 with the encouragement of the Reverend Henry Ward Beecher (abolitionist known for his “Beecher Bibles” (guns) that he sent to Kansas abolitionists and father of Harriet Beecher Stowe, writer of Uncle Tom’s Cabin) and a contribution from a Quaker philanthropist, Miner opened The Colored Girls School in Washington, D.C.

Feminist Abolitionist Myrtilla Miner

Myrtilla Miner

Enrollment grew with the help of continued Quaker contributions as well as a $1000 contribution from Harriet Beecher Stowe from her Uncle Tom’s Cabin royalties.

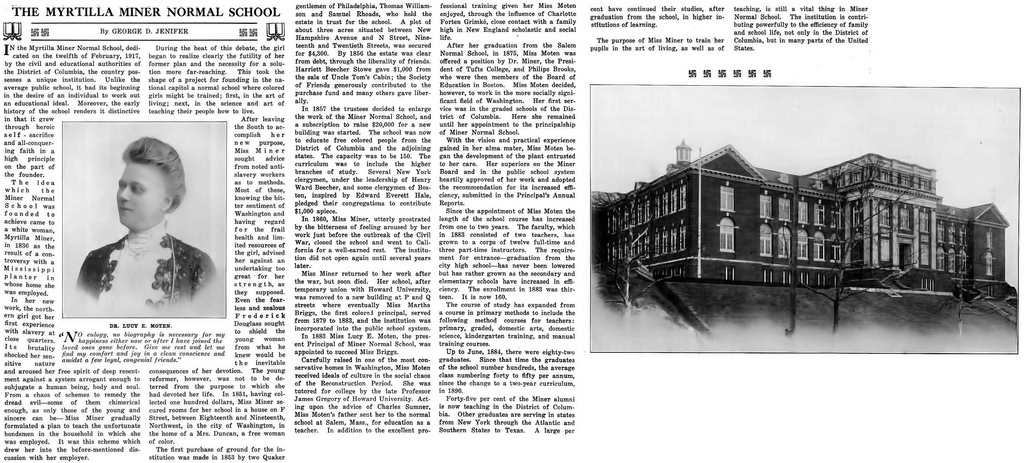

The school offered primary schooling and classes in domestic skills, but its emphasis was always on training teachers. By 1858 six former students were teaching in schools of their own. The school closed during the Civil War and Miner moved to California because of poor health.

She suffered a carriage accident in 1864 and died on December 17, 1864 shortly after her return to Washington, D.C.

On January 29, 1865, among the many deaths listed under “The Dead of 1864” the New York Times reported, “MINER, Miss MYRTILLA, an authoress and philanthropist, died at Washington, D.C.”

Feminist Abolitionist Myrtilla Miner

After Miner’s death

The Civil War ended and the school reopened as the Institution for the Education of Colored Youth. From 1871 to 1876 it was associated with Howard University. In 1879, as Miner Normal School, it became part of the District of Columbia public school system.

Feminist Abolitionist Myrtilla Miner

Washington Normal School

Similarly, Washington Normal School (later Wilson Teachers College) was established in 1873, as a school for white girls. In 1929, Congress converted both schools into four-year teachers colleges.

In 1955, after the US Supreme Court decision of Brown v. Board of Education, the two colleges merged to form the District of Columbia Teachers College.

On August 1, 1977, the Board of Trustees announced the consolidation of the District of Columbia Teachers College, the Federal City College, and the Washington Technical Institute into the University of the District of Columbia.

References:

- Daily Kos article

- Encyclopedia Britannica article

- Women History blog

- PDF “A memoir” by Ellen M O’Connor

- Syracuse dot com article