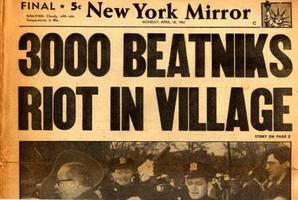

NYC Bans Folk Music

Anniversary of the “Beatnik Riot”

April 9, 1961

NYC Bans Folk Music

World Power Anomie

After World War II, many young adults, disenchanted with the horrors and atrocities of two global wars less than 25 years apart, broke away from prevailing cultural mores. They sought out an anti-conformist life style that isolated them from what they saw as a morally corrupt society.

Some found that isolation with those whom American society had already segregated. Some found it in the arts.

Jack Kerouac referred to himself and those like him as part of a Beat Generation. (NY Times magazine article). His use carried with it the notion of being tired, but Kerouac mixed in the ideas of “upbeat”, and “beatific.”

NYC Bans Folk Music

Cold War

On October 4, 1957, the Soviet Union successfully launched the first satellite, Sputnik. The Cold War had increasingly heated in the late 1950s. Growing up as a Boomer meant learning to hate, to distrust, and be anti-anything associated with the USSR. Catholics prayed for its conversion after every Sunday Mass.

The arms race continued. Sputnik launched the space race, in many ways an offshoot of that arms race.

What better way to label a disenchanted group, the Beats, a group that mainstream citizens and media saw as un-American? Associate them with Communism.

NYC Bans Folk Music

Beatniks

On April 2, 1958, Herb Caen of the San Francisco Chronicle wrote, “Look magazine, preparing a picture spread on S.F.’s Beat Generation (oh, no, not AGAIN!), hosted a party in a No. Beach house for 50 Beatniks, and by the time word got around the sour grapevine, over 250 bearded cats and kits were on hand, slopping up Mike Cowles’ free booze. They’re only Beat, y’know, when it comes to work . . . “

Thus the Beats became Beatniks. It was not a compliment.

Some Beats loved jazz. Some Beats loved folk music. Both sometimes played outside with friends in NYC’s Greenwich Village, particularly Washington Square Park, busking or simply entertaining themselves.

NYC Bans Folk Music

Newbold Morris

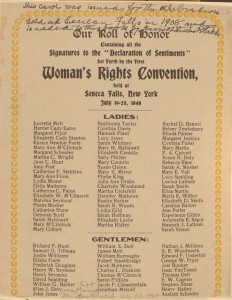

Despite the First Amendment’s guarantee of free speech, on March 28, 1961, NYC Park Commissioner Newbold Morris notified his staff to limit permits issued for musical performances in Washington Square to “legitimate” artistic groups. He also asked the police to issue summonses to guitarists, bongo drummers, and folk singers who did not have permits.

On April 9, 1961 Greenwich Village folk song fans battled the police for two hours in Washington Square. Police arrested ten demonstrators. Several persons, including three policemen, were hurt.

From the Greenwich Village Society for Historic Preservation site: The protest was arranged by Izzy Young, head of the Folklore Center on MacDougal Street. A group of protestors who sat in the fountain singing “We Shall Not be Moved” was attacked by police with billy clubs. Another group sang the Star Spangled Banner, thinking police would not attack such a display of patriotism- they were wrong.

NYC Bans Folk Music

Here is that film

NYC Bans Folk Music

Continued support for ban

Two days later NYC Mayor Robert F Wagner, announced his support of the ban.

On April 20, 1961 the Community Planning Board voted to uphold Park Commissioner Newbold Morris’ ban against folk-singing in Washington Square Park.

On April 30, 1961 police arrested William French, a student, at another demonstration by folk-music fans in Washington Square Park. That arrest nearly set off a riot. It also raised charges of police brutality.

NYC Bans Folk Music

State Supreme Court

On May 4, 1961 NYC’s ban against folk singing in Washington Square Park was upheld by the State Supreme Court.

On May 7, 1961, singers marched back into Washington Square Park and sang for the first time in four weeks without hindrance from the police. They sang a capella. They had discovered that Park Department ordinances require a permit only for “minstrelsy” – singing with instruments, but not for unaccompanied song.

On May 12, 1961 NYC Mayor Wagner announced that folk singing, with instrumental accompaniment, would be permitted in Washington Square “on a controlled basis.”

On June 5, 1961 a grand jury cleared William French of charges associated with the April 30 Washington Square demonstration.

NYC Bans Folk Music

Appellate Division decision

And on July 6, 1961, the Appellate Division of the NY State Supreme Court unanimously reversed a lower court decision that had supported the city’s former ban on folk singing in Washington Square.

Community displeasure with those seen as outsiders and disruptive was not new and continued. Eight years later in Wallkill, NY, a group of community leaders succeeded in keeping out a group that sought to play their music. That event, of course, was called the Woodstock Music and Art Fair.

Reference >>> NPR report on Washington Square folk music ban