Dylan Becomes Dylan

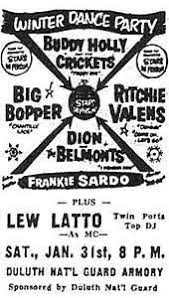

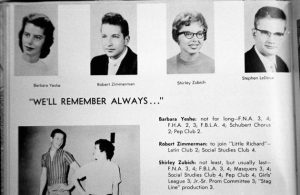

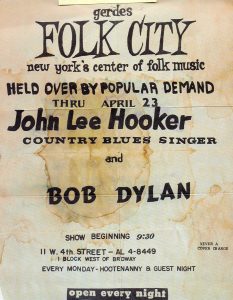

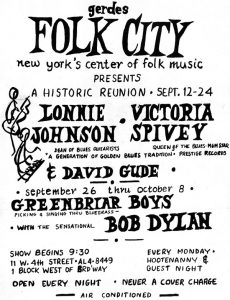

Bobby Zimmerman had been calling himself Bob Dylan since the spring of 1958 and August 2, 1962 he legally changed his name to Bob Dylan. but even with the legal name change, he was not the Bob Dylan whose name all immediately recognized.

His talent was there. His stage presence there.

With Albert Grossman and Joan Baez adding themselves into the cocktail THAT Bob Dylan arose.

In 1966, though, Bob Dylan would came crashing down, both literally and figuratively.

Dylan Becomes Dylan

Albert Grossman

August 30, 1962: Dylan and Albert Grossman signed a management agreement. It gave Grossman four years as Bob’s exclusive manager, with an option to extend the contract for a further three.

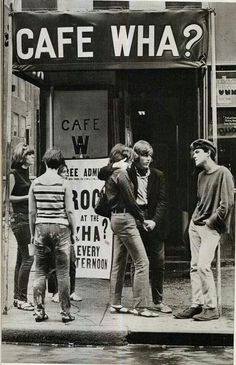

In September 1962: Dylan wrote A Hard Rain’s A-Gonna Fall in the basement of the Village Gate, in a small apartment occupied by Chip Monck, later to become one of the most sought-after lighting directors in rock music and a voice associated with the Woodstock Festival.

Dylan Becomes Dylan

First single flops

December 14, 1962: Columbia Records released Bob Dylan’s first single: Mixed Up Confusion. It flopped.

In January 1963: back together with Suze Rotolo (who herself was back from a seven-month stay Italy–a deliberate escape from Dylan). The relationship was a strained one and one that Dylan was not true to.

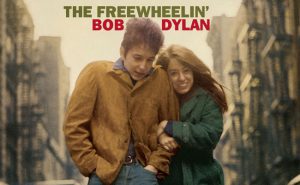

Despite the increasing estrangement, in February 1963 Columbia staff photographer Don Hunstein photographed Dylan and Suze Rotolo for the cover of The Freewheelin’ Bob Dylan.

Hunstein recalled: “We went down to Dylan’s place on Fourth Street, just off Sixth Avenue, right in the heart of the Village. It was winter, dirty snow on the ground . . . Well, I can’t tell you why I did it, but I said, Just walk up and down the street. There wasn’t very much thought to it. It was late afternoon you can tell that the sun was low behind them. It must have been pretty uncomfortable, out there in the slush.”

Dylan Becomes Dylan

Last Thoughts

April 12, 1963: at New York’s Town Hall Bob Dylan recited “Last Thoughts on Woody Guthrie,” a long evocation of old memories, a youth searching for himself by the railroad tracks, down the road, in fields and meadows, on the banks of streams, in the “trash can alleys.”

And, he says, somehow during that search Woody was his companion. There’s this book comin’ out, an’ they asked me to write something about Woody…Sort of like “What does Woody Guthrie mean to you?” in twenty-five words…

And I couldn’t do it — I wrote out five pages and… I have it here, it’s…Have it here by accident, actually… but I’d like to say this out loud…So… if you can sort of roll along with this thing here, this is called…

Dylan Becomes Dylan

Ed Sullivan walkout

May 12, 1963: the still unknown Dylan walked off the set of the “Ed Sullivan Show” (the country’s highest-rated variety show) after network censors rejected “Talkin’ John Birch Paranoid Blues,” the song he planned on performing. The song was satirical talking-blues number skewering the ultra-conservative John Birch Society and its tendency to see covert members of an international Communist conspiracy behind every tree. Dylan had auditioned “John Birch” days earlier and had run through it for Ed Sullivan himself without any concern being raised. But during dress rehearsal on the day of the show, an executive from the CBS Standards and Practices department informed the show’s producers that they could not allow Dylan to go forward singing “John Birch.”

Dylan Becomes Dylan

Festivals & Rallies

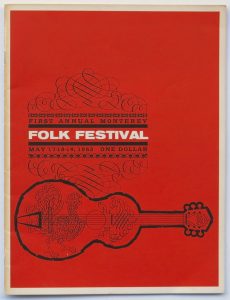

May 17, 1963: the first Monterey Folk Festival took place over three days in Monterey, California. The festival featured Joan Baez, Bob Dylan and Peter Paul and Mary. Baez, had a home in Carmel Highlands, was a huge star at the time, while Dylan was a still a newcomer making a name for himself.

May 17, 1963: the first Monterey Folk Festival took place over three days in Monterey, California. The festival featured Joan Baez, Bob Dylan and Peter Paul and Mary. Baez, had a home in Carmel Highlands, was a huge star at the time, while Dylan was a still a newcomer making a name for himself.

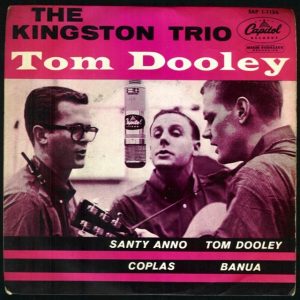

Dylan was not treated kindly by that Monterey audience, who had come to see more traditional folks acts such as Peter, Paul and Mary (who ironically would have a hit that summer with Dylan’s “Blowin’ in the Wind”), the Weavers and the New Lost City Ramblers.

As described in the excellent book about that era, David Hajdu’s “Positively 4th Street,” “The Monterey audience, which was largely unfamiliar with Dylan’s style, responded poorly, talking loudly over his singing.”

“He went over very badly,” said Barbara Dane, the festival’s host, in Hajdu’s account. “He didn’t play very long, and it felt like he was on for an hour. I think people were laughing.” Even though he did three of his hardest-hitting protest songs, “Talkin’ John Birch Paranoid Blues,” “A Hard Rain’s A-Gonna Fall” and “Masters of War,” the response was so bad it prompted Baez to walk out unannounced and admonish the audience. “She wanted everyone to know, she said, that this young man had something to say,” Hajdu wrote. “He was singing about important issues, and he was speaking for her and everyone who wanted a better world. They should listen, she said — she ordered them, nearly:Listen!”

They performed Dylan’s “With God on Our Side” together, their voices an odd match, “salt pork and meringue,” but Hadju wrote, “the tension between their styles made their presence together all the more compelling.” They left the stage with “people cheering.”

Freewheelin’

May 27, 1963: released his second album, The Freewheelin Bob Dylan with the Suze/Bob album cover.

In a 2008 New York Times article Rotolo said: “He wore a very thin jacket, because image was all. Our apartment was always cold, so I had a sweater on, plus I borrowed one of his big, bulky sweaters. On top of that I put on a coat. So I felt like an Italian sausage. Every time I look at that picture, I think I look fat.”

In her memoir, A Freewheelin’ Time, Rotolo analyzed the significance of the cover image: It is one of those cultural markers that influenced the look of album covers precisely because of its casual down-home spontaneity and sensibility. Most album covers were carefully staged and controlled, to terrific effect on the Blue Note jazz album covers … and to not-so great-effect on the perfectly posed and clean-cut pop and folk albums. Whoever was responsible for choosing that particular photograph for The Freewheelin’ Bob Dylan really had an eye for a new look.

Critic Janet Maslin summed up the iconic impact of the cover as “a photograph that inspired countless young men to hunch their shoulders, look distant, and let the girl do the clinging.”

The album was an immediate success selling 10,000 copies a month

Greenwood, Mississippi

July 6, 1963: Dylan first performed “Only a Pawn in Their Game” at a voter registration rally in Greenwood, Mississippi. The song refers to the murder of Medgar Evers.

Bernice Johnson Reagon would later tell critic Robert Shelton that “‘Pawn’ was the very first song that showed the poor white was as victimized by discrimination as the poor black. The Greenwood people didn’t know that Pete [Seeger], Theo[dore Bikel] and Bobby [Dylan] were well known. (Seeger and Bikel were also present at the registration rally.) They were just happy to be getting support. But they really like Dylan down there in the cotton country.”

Also on this date, Peter, Paul and Mary’s cover of Dylan’s “Blowin’ In the Wind” reached #2 on Billboard with sales exceeding one million.

Newport 1963

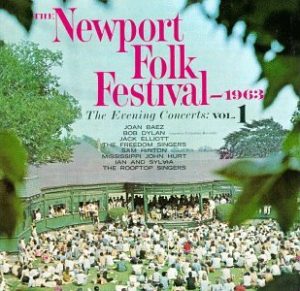

July 26 – 28, 1963: festival included Phil Ochs, Pete Seeger, and Joan Baez who introduced Dylan as her guest.

July 26 – 28, 1963: festival included Phil Ochs, Pete Seeger, and Joan Baez who introduced Dylan as her guest.

August 3, 1963: Dylan and Joan Baez, a couple, begin a tour together. She is the headline name, but Dylan is the star. The tour provided a huge boost to Dylan’s career.

Dylan Becomes Dylan

Woodstock

That same summer, manager Albert Grossman bought a house in Bearsville, NY near Woodstock. He converted space above the barn as a guest room for Dylan. Both he and Baez will be frequent visitors.

August 17, 1963: Peter, Paul, and Mary’s cover of “Blowin’ In the Wind” reached number two on the Billboard pop chart, with sales exceeding one million copies.

August 28, 1963: Martin Luther King, Jr delivered his I Have a Dream speech.

Bob Dylan and Joan Baez will also perform, he “Only A Pawn In Their Game.”

Dylan Becomes Dylan

Sam Cooke

October 8, 1963: after hearing Bob Dylan’s “Blowin’ in the Wind” earlier in the year, Sam Cooke was greatly moved that such a poignant song about racism in America could come from someone who was not black. While on tour in May and after speaking with sit-in demonstrators in Durham, North Carolina following a concert, Cooke returned to his tour bus and wrote the first draft of what would become “A Change Is Gonna Come“. The song also reflected much of Cooke’s own inner turmoil. Known for his polished image and light-hearted songs such as “You Send Me” and “Twistin’ the Night Away“, he had long felt the need to address the situation of discrimination and racism. However, his image and fears of losing his largely white fan base prevented him from doing so.

“A Change Is Gonna’ Come,” very much a departure for Cooke, reflected two major incidents in his life. The first was the death of Cooke’s 18-month-old son, Vincent, who died of an accidental drowning in June of that year. The second major incident came this date when Cooke and his band tried to register at a “whites only” motel in Shreveport, Louisiana and were summarily arrested for disturbing the peace. Both incidents are represented in the weary tone and lyrics of the piece, especially the final verse: There have been times that I thought I couldn’t last for long/but now I think I’m able to carry on/It’s been a long time coming, but I know a change is gonna come.

Cooke would not record the song until November 1964.

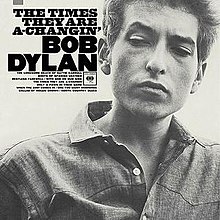

October 23, 1963: Dylan recorded ‘The Times They Are A-Changin‘ at Columbia Recording Studios in New York City. Dylan wrote the song as a deliberate attempt to create an anthem of change for the time, influenced by Irish and Scottish ballads.

Dylan Becomes Dylan

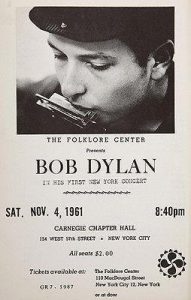

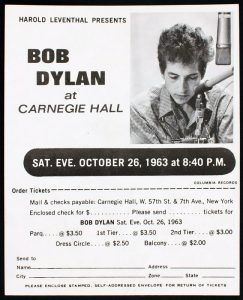

Carnegie Hall

October 26, 1963: Dylan gave a sold-out concert at Carnegie Hall. His parents, Abe and Beatty Zimmerman came in from Hibbing, MN for the concert.

October 26, 1963: Dylan gave a sold-out concert at Carnegie Hall. His parents, Abe and Beatty Zimmerman came in from Hibbing, MN for the concert.

November 2 – December 6, 1963: Peter, Paul, and Mary’s Blowin’ In the Wind is the Billboard #1 album. The best-known cover of Bob Dylan’s song. In the liner notes to Dylan’s original release, Nat Hentoff calls the song “a statement that maybe you can say to make yourself feel better… as if you were talking to yourself.” The song was written around the time that Suze Rotolo indefinitely prolonged her stay in Italy. The melody is based on an older song, “Who’s Gonna Buy Your Chickens When I’m Gone”. The melody was taught to Dylan by folksinger Paul Clayton, who had used the melody in his song “Who’s Gonna Buy Your Ribbons When I’m Gone?”

Newsweek mocks Dylan

November 4, 1963: the edition o fNewsweek carried an article that mocked Dylan’s self made image and pointed out that he had grown up in a middle class family in Hibbing, MN. The article showed him as a vain and self-promoting. “Why Dylan—he picked the name in admiration for Dylan Thomas—should bother to deny his past is a mystery. Perhaps he feels it would spoil the image he works so hard to cultivate—with his dress, with his talk, with the deliberately atrocious grammar and pronunciation in his songs”

Dylan mocks Paine

December 13, 1963: the Emergency Civil Liberties Committee gave Dylan the Tom Paine award. It was an honor given to a public figure that supported social justice. A drunk Dylan spoke without preparing and made fun of those present. He also said he could understand how Lee Harvey Oswald felt.

December 13, 1963: the Emergency Civil Liberties Committee gave Dylan the Tom Paine award. It was an honor given to a public figure that supported social justice. A drunk Dylan spoke without preparing and made fun of those present. He also said he could understand how Lee Harvey Oswald felt.

Dylan Becomes Dylan

The Times They Are a’Changin’

January 13, 1964: released his third album, The Times They Are a-Changin’

January 13, 1964: released his third album, The Times They Are a-Changin’

Dylan had recorded it over six sessions between August 6 – October 31, 1963 at Columbia Studios, New York City.

Dylan Becomes Dylan

On the Road

February 3, 1964: Dylan, along with friends Victor Maymudes (his first road manager), Pete Karman (Suze Rotolo’s request to keep an eye on Dylan), and Paul “Pablo” Clayton (his tune was appropriated by Dylan for “Don’t Think Twice.”

Though Dylan would play a few concerts on the trip, the main purpose of the trip was to imitate Jack Kerouac’s novel On the Road.

Among the songs he wrote on the trip were: “Chimes of Freedom” and “Mr Tambourine Man”

Steve Allen Show

February 25, 1964: Dylan appeared on the Steve Allen Show. Dylan’s discomfort with interviews was easily seen and when asked about his song, “The Lonesome Death of Hattie Carroll” Dylan’s response was to sing the song.

Mr Tambourine Man

June 9, 1964: during an evening session Bob Dylan recorded Mr. Tambourine Man at Columbia Recording Studios in New York City. This was the first session for the Another Side Of Bob Dylan, which saw Dylan recording fourteen original compositions that night. Ultimately, Mr Tambourine Man would not be included on the album.

In August, 1964: “I’m Going to Get My Baby Out of Jail” by Len Chandler & Bernice Johnson Reagon. Dylan “stole” the Len Chandler tune to accompany his “The Death of Emmett Till.”

Dylan Becomes Dylan

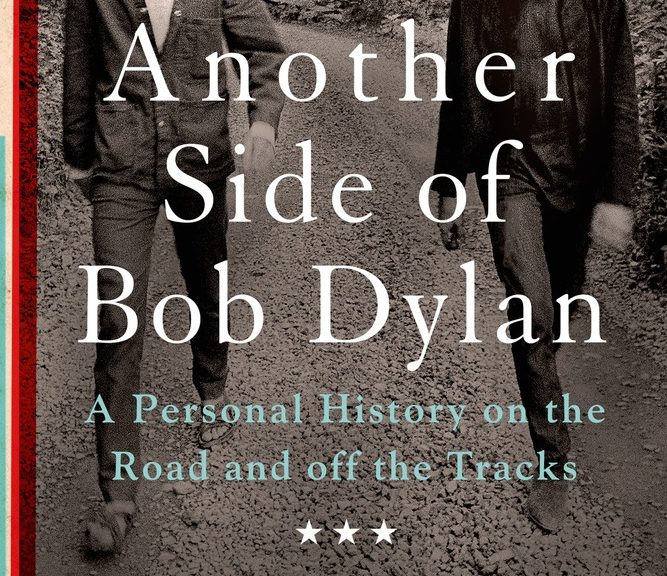

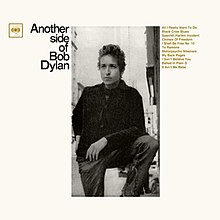

Another Side of Bob Dylan

August 8, 1964: released fourth album, Another Side of Bob Dylan. Became 1964’s 10th biggest selling album. Recorded: June 9 (only!)

August 8, 1964: released fourth album, Another Side of Bob Dylan. Became 1964’s 10th biggest selling album. Recorded: June 9 (only!)

“In Bob’s folk waltz “To Ramona,” you hear Bob Dylan acknowledge their [Dylan and Joan Baez] diverging lives for the first time in song. He sings about her idealism and how it will eventually lead to her downfall (“It grieves my heart, love/To see you tryin’ to be a part of/A world that just don’t exist”), her struggle to remain approachable and “common” whilel trying to keep her privacy (“I’ve heard you say many times/That you’re better ‘n no one/And no one is better ‘n you/If you really believe that/You know you have/Nothing to win and nothing to lose”) and his inability to help her in any of her struggles (“I’d forever talk to you/But soon my words/They would turn into a meaningless ring/For deep in my heart/I know there is no help I can bring”). When you listen to the song, you get to hear the struggles of being one of the most famous couples in the world. And beyond that, you hear first hand, the story of a couple growing apart.

Dylan Becomes Dylan

Beatles Meet Dylan

August 28, 1964: The Beatles played a concert at New York’s Forest Hills Tennis Stadium. After the concert, the group was taken back to their suite at the city’s Hotel Delmonico. Journalist Al Aronowitz had came down from Woodstock, NY with his friend Bob Dylan, and brought him up to The Beatles hotel suite. John Lennon asked Dylan what he’d like to drink, and Dylan said “cheap wine.”

The Beatles offer Dylan their drug of choice which was speed. Dylan suggested marijuana, which the band while aware of had never tried. Hearing that they had never smoked pot, Dylan was quite surprised and said that he always thought the band sang “I get high” in their song “I Wanna Hold Your Hand.” John corrected him, telling him that the phrase was “I can’t hide.”

Dylan lit up a joint and Lennon made Ringo smoke it first. Eventually each member of the band got his own. Paul was interested with the thoughts it produced and asked Mal Evans to follow him around with a notepad and take down everything he said.

Dylan Becomes Dylan

Byrds Success Becomes Dylan’s Success

January 20, 1965: The Byrds entered the studio to record “Mr Tambourine Man,” what would become the title track of their debut album and, incidentally, the only Bob Dylan song ever to reach #1 on the U.S. pop charts.

Aiming consciously for a vocal style in between Bob Dylan and John Lennon, Roger McGuinn sang lead, with Gene Clark and David Crosby providing the complex harmony that would, along with McGuinn’s jangly electric 12-string Rickenbacker guitar, form the basis of the Byrds’ trademark sound.

Dylan Becomes Dylan

Dylan’s phenomenal success led to constant touring under the aegis of manager Albert Grossman.

Dylan would soon break away from his folk image, his acoustic image, and quit working on “Maggie’s Farm.”

The break would lead to an even more frenetic life. One that he will eventually and deliberately chose to leave.