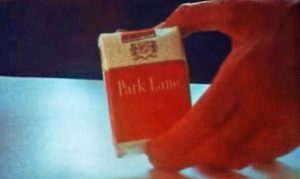

Vietnam’s Park Lane Cigarettes

Disclaimer: Though of age, I did not serve in Vietnam. I had a college deferment and then was fortunate to get a 332 lottery number. When I meet veterans who said they were in Vietnam and then ask what I was doing, I explain that I was trying to get them home.

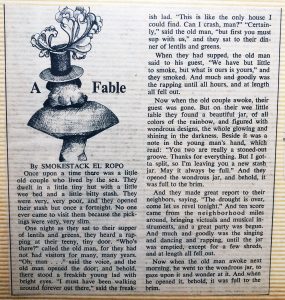

Smokestack El Ropo

I, like many in the late 60s, had a subscription to Rolling Stone magazine. Smokestack El Ropo occasionally published “Fables” in it. Each typically had to do with people about to have, having, just having had an enhanced experience.

In 1972, Straight Arrow books published Smokestack El Ropo’s Bedside Reader, which was described as “A heavy-duty compendium of fables, lore and hot dope tales, from America’s only rolling newspaper.”

Vietnam’s Park Lane Cigarettes

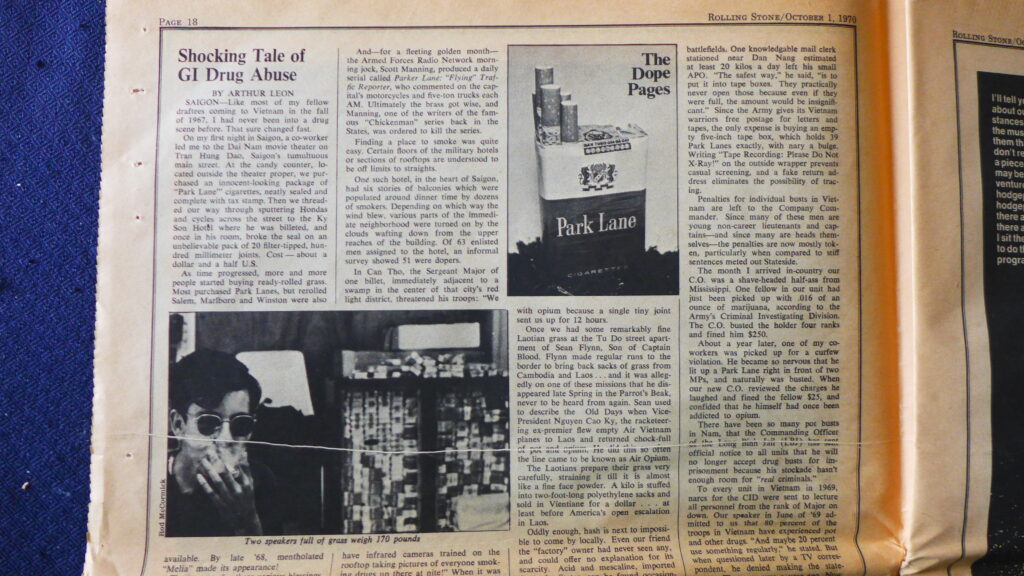

Shocking Tale of GI Drug Abuse

Since there weren’t enough Fables to fill a book, Smokestack included writings by many others, but each fit the theme. Among those others was Arthur Leon’s Shocking Tale of GI Drug Abuse. The title was misleading in the sense that the troop behavior described was not abuse, but simply getting high.

Like any first-hand account, we must take its veracity with a grain of salt or one toke over the line, so let’s be careful.

Leon describes his arrival in Saigon and how quickly a fellow GI introduced him to its thriving drug scene. The most common drug was local cannabis and the most common cannabis delivery system was cigarettes. Vietnamese workers removed the tobacco from actual packs of cigarettes and refilled them with cannabis. Park Lane cigarettes were the most popular refill, but Salem, Winston, and Marlboro were also around.

Leon and friends became friendly with these entrepreneurs and “…were able to get our price down to the equivalent of four US dollars per carton of 200.”

Vietnam’s Park Lane Cigarettes

GI Drug Use

Drug use by GIs was not permitted and subject to severe punishment. According to the Thailand Law Forum site:

A survey in 1966 by the U.S. military command in Saigon found that there were 29 fixed outlets for the purchase of marijuana. Some enterprising individuals removed the tobacco from regular tailor-made cigarettes and repacked them with dried cannabis and sold them by the pack. These pre-rolled and pre-packaged marijuana cigarettes were sold under the brand names Craven “A” and Park Lane.

Reports indicate that US troops began smoking marijuana soon after their arrival in 1963. Although marines were subject to being court-martialed for possessing even the smallest amount of cannabis, the army only prosecuted dealers and users of hard drugs. The arrests for marijuana possession reached a peak of up to 1,000 a week.

In 2002, Peter Brush in a Free Republic article wrote about how GIs had an unwritten rule that cannabis was off limits out in country and lives depended on being alert. But back in Saigon or away from the fighting, enforcement was less important. The article goes on…

In fact, marijuana use was a problem chiefly because it conflicted with American civilian and military values. Use of marijuana did not constitute an operational problem. Smoking in rear areas did not impact operations. Use among combat personnel took place when units stood down rather than in the field. The commanding general of the 3rd Marine Division noted, “There is no drug problem out in the hinterlands, because there was a self-policing by the troops themselves.” Combat soldiers knew their survival depended on having clear mental faculties.

Army Major Joel Kaplan of the 98th Medical Detachment, while noting the high rate of marijuana use by military personnel, said, “I think alcohol is a much more dangerous drug than marijuana.” One Air Force officer understood well the difference: “When you get up there in those early hours, you want the klunk you’re flying with to be able to snap to. He’s a lot more likely to be fresh if he smoked grass the night before than if he was juiced.”

A much larger problem was on the horizon for American military commanders in Vietnam—heroin. When its use became commonplace, one Army commanding officer rationally said of marijuana use, “If it would get them to give up the hard stuff, I would buy all the marijuana and hashish in the Delta as a present.”

Vietnam’s Park Lane Cigarettes

Clever GIs

Park Lane cigarettes were widely advertised outdoors on billboards and posters, and in newspapers.The Military Assistance Command, Vietnam counter-attacked with posters of their own. In Vietnam, the most enjoyable things were rated “10” and the least rated “1.” The MACV poster–a soldier smoking with the curl of the cigarette smoke spelling POT–were extremely popular with the troops. They hung the poster in their barracks with the 10’s zero crossed out.

Scott Manning, an Armed Forces Radio Network DJ (not AFRN radio DJ Adrian Cronauer upon whom Robin Williams’s character in Good Morning Vietnam was loosely based) produced a daily serial called Parker Lane: “Flying” Traffic Reporter who commented on Saigon’s scooter and truck congestion. The brass killed the serial.

Vietnam’s Park Lane Cigarettes

Mail home

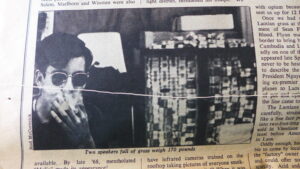

Arthur Leon also speaks of GIs taking advantage of the mail. When heading home, the military would send up to a 200 pound parcel for the GI, sometimes for free or at least at a very reduced rate. Leon tells the story of his roommate buying two Japanese speakers, gutting them, filling each one with 50 cartons of “modified” Park Lane cigarettes, re-packaging the speakers, and getting them home the day after his discharge.

On a much smaller scale, GIs would buy a tape box (reel-to-reel) which held 39 Park Lanes. Wrap the box, write “Tape Recording: Please Do Not X-Ray” on the outside, write a fake return address, and send it home. Free.

Vietnam’s Park Lane Cigarettes

Park Lane Stateside

On January 16, 1971, the New York Times published a short article on page 52 about Park Lane’s presence in the US.

Here is a piece of a video with an American reporter in Saigon looking for weed and finding many GIs ready and willing to speak about it, its accessibility, and Park Lane.

Rod McCormick

A reader of this post contacted me to say that he’d provided some pictures for an October 1970 Rolling Stone magazine article about Park Lane.