Cuban Missile Crisis

We know that nothing historic happens by itself. We just forget.

Boomers remember the Cuban missile crisis as an October 1962 event, an event that grew from a simple announcement into the shuddering fear of nuclear apocalypse.

What follows is a chronologically simplified list of the various events that preceded the crisis, the crisis itself, and its aftermath.

Cuban Missile Crisis

Bay of Pigs & aftermath

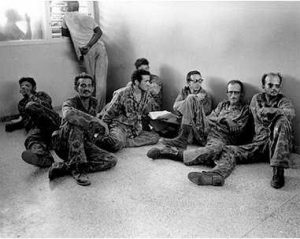

April 24, 1961: President Kennedy accepted “sole responsibility” following the failed Bay of Pigs invasion of Cuba and in November he authorized an aggressive covert operations (code name Operation Mongoose) against Fidel Castro. Air Force General Edward Lansdale led the operation.

Operation Mongoose’s goal was to remove the communists from power to “help Cuba overthrow the Communist regime,” including its leader Fidel Castro. It aimed “for a revolt which can take place in Cuba by October 1962”. US policy makers also wanted to see “a new government with which the United States can live in peace”. [PBS story re Mongoose]

February 3, 1962: President Kennedy banned all trade with Cuba.

Cuban Missile Crisis

US missiles in Turkey

Deployed in 1959, in April 1962, U.S. Jupiter missiles in Turkey became operational. US personnel reported all positions “ready and manned.”

USSR missiles in Cuba

May 30, 1962: Fidel Castro informed visiting Soviet officials that Cuba would accept the deployment of nuclear weapons.

August 17, 1962: US Central Intelligence Agency Director John McCone stated at a high-level meeting that circumstantial evidence suggested that the Soviet Union was constructing offensive missile installations in Cuba. Dean Rusk and Secretary of Defense Robert McNamara disagreed with McCone, arguing that the build-up was purely defensive.

Twelve days later, on August 29, a high-altitude U-2 surveillance flight provided conclusive evidence of the existence of missile sites at eight different locations in Cuba.

September 18, 1962: the Soviet Union conducted an above ground nuclear test of 1.5 – 10 megatons. [NYT article]

September 19, 1962: the United States Intelligence Board (USIB) approved a report on the Soviet arms buildup in Cuba. Its assessment, stated that some intelligence indicates the ongoing deployment of nuclear missiles to Cuba.

Cuban Missile Crisis

Cuba at the UN

October 7, 1962: Cuban President Osvaldo Dorticós spoke at the UN General Assembly: “If … we are attacked, we will defend ourselves. I repeat, we have sufficient means with which to defend ourselves; we have indeed our inevitable weapons, the weapons, which we would have preferred not to acquire, and which we do not wish to employ.”

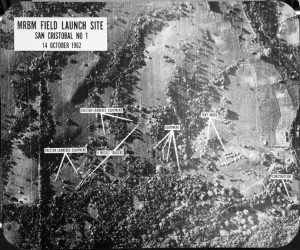

October 14, 1962: a US Air Force U-2 plane on a photo-reconnaissance mission captured proof of Soviet missile bases under construction in Cuba. Four days later, on October 18, President Kennedy met with Soviet Minister of Foreign Affairs, Andrei Gromyko, who claimed the weapons were for defensive purposes only. Not wanting to expose what he already knew, and wanting to avoid panicking the American public, Kennedy did not reveal that he was already aware of the missile build-up.

October 16, 1962: the Defense Intelligence Agency laid out the details of the Soviet buildup to the Joints Chiefs of Staff.

October 1962 Cuban Missile Crisis

Public announcement

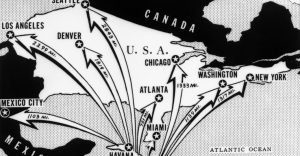

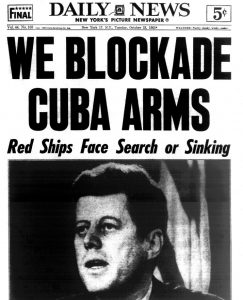

October 22, 1962: President Kennedy announced the existence of Soviet missiles in Cuba and ordered a naval blockade. The Joint Chiefs of Staff unanimously agreed that a full-scale attack and invasion was the only solution.

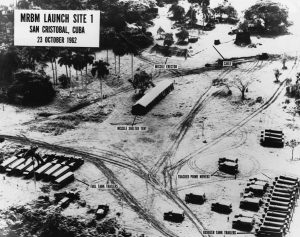

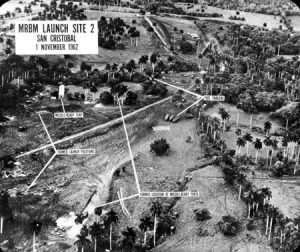

October 23, 1962: evidence presented by the U.S. Department of Defense of Soviet missiles in Cuba. This low level photo of the medium range ballistic missile site under construction at Cuba’s San Cristobal area. A line of oxidizer trailers is at center.

Added since October 14, were fuel trailers, a missile shelter tent, and equipment. The missile erector now lies under canvas cover. Evident also is extensive vehicle trackage and the construction of cable lines to control areas

October 24, 1962: the Soviet news agency Telegrafnoe Agentstvo Sovetskogo Soyuza (TASS) broadcast a telegram from Nikita Khrushchev to President Kennedy, in which Khrushchev warned that the United States’ “pirate action” would lead to war. President John F. Kennedy spoke before reporters during a televised speech to the nation about the strategic blockade of Cuba, and his warning to the Soviet Union about missile sanctions.

Cuban Missile Crisis

October 25, 1962

The Chinese People’s Daily announced that “650,000,000 Chinese men and women were standing by the Cuban people”.

At the United Nations, ambassador Adlai Stevenson confronted Soviet Ambassador Valerian Zorin in an emergency meeting challenging him to admit the existence of the missiles.

The Soviets responded to the blockade by turning back 14 ships presumably carrying offensive weapons.

Cuban Missile Crisis

UN confrontation

October 26, 1962: in one of the most dramatic verbal confrontations of the Cold War, American U.N. Ambassador Adlai Stevenson asked his Soviet counterpart during a Security Council debate whether the USSR had placed missiles in Cuba. Meanwhile, B-52 bombers were dispersed to various locations and made ready to take off, fully equipped.

Cuban Missile Crisis

Rudolf Anderson shot down

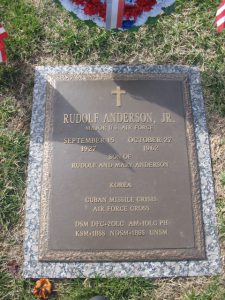

October 27, 1962: Radio Moscow began broadcasting a message from Khrushchev. The message offered a new trade, that the missiles on Cuba would be removed in exchange for the removal of the Jupiter missiles from Italy and Turkey. Cuba shot down a US U2 plane with surface to air missile killing the pilot, Rudolf Anderson. U.S. Army anti-aircraft rockets sat, mounted on launchers and pointed out over the Florida Straits in Key West, Florida.

Cuban Missile Crisis

Detente

October 28, 1962: after much deliberation between the Soviet Union and Kennedy’s cabinet, Kennedy secretly agreed to remove all missiles set in southern Italy and in Turkey, the latter on the border of the Soviet Union, in exchange for Khrushchev removing all missiles in Cuba. Nikita Khrushchev announced that he had ordered the removal of Soviet missile bases in Cuba.

November 6, 1962: Rudolph Anderson’s body interred in Greenville, South Carolina at Woodlawn Memorial Park.

Cuban Missile Crisis

Hot line

June 20, 1963: to lessen the threat of an accidental nuclear war, the US and the Soviet Union agreed to establish a “hot line” communication system between the two nations.

August 30, 1963: the “Hot Line” communications link between the White House, Washington D.C. and the Kremlin, Moscow, went into operation to provide a direct two-way communications channel between the American and Soviet governments in the event of an international crisis.

It consisted of one full-time duplex wire telegraph circuit, routed Washington- London- Copenhagen- Stockholm- Helsinki- Moscow, used for the transmission of messages and one full-time duplex radiotelegraph circuit, routed Washington- Tangier- Moscow used for service communications and for coordination of operations between the two terminal points. Note, this was not a telephone voice link.

Cuban Missile Crisis

Nuclear test ban

October 7, 1963: President John F. Kennedy signed the documents of ratification for a nuclear test ban treaty with Britain and the Soviet Union. [NYT article]

Cuban Missile Crisis

Cuban/US relations

Castro was furious that Khrushchev had not consulted him before making his bargain with Kennedy to end the crisis — and furious as well that U.S. covert action against him had not ceased. In September 1963, Castro appeared at a Brazilian Embassy reception in Havana and warned, “American leaders should know that if they are aiding terrorist plans to eliminate Cuban leaders, then they themselves will not be safe.”

November 18, 1963: at the Americana Hotel in Miami President John F. Kennedy told the Inter-American Press Association that only one issue separated the United States from Fidel Castro’s Cuba: Castro’s “conspirators” had handed Cuban sovereignty to “forces beyond the hemisphere” (meaning the Soviet Union), which were using Cuba “to subvert the other American republics.” Kennedy said, “As long as this is true, nothing is possible. Without it, everything is possible.”

That same day, Ambassador William Attwood, a Kennedy delegate to the United Nations, secretly called Castro’s aide and physician, Rene Vallejo, to discuss a possible secret meeting in Havana between Attwood and Castro that might improve the Cuban-American relationship. Attwood had been told by Castro’s U.N. ambassador, Carlos Lechuga, in September 1963, that the Cuban leader wished to establish back-channel communications with Washington.

Kennedy’s national security adviser, McGeorge Bundy, told Attwood that J.F.K. wanted to “know more about what is on Castro’s mind before committing ourselves to further talks on Cuba.” He said that as soon as Attwood and Lechuga could agree on an agenda, the president would tell him what to say to Castro.

November 19, 1963: Kennedy had settled the Cuban crisis, in part, by pledging that the US would not invade Cuba; however that pledge was conditioned on the presumption that Castro would stop trying to encourage other revolutions like his own throughout Latin America.

Tuesday 19 November 1963: the evening before President Kennedy’s final full day at the White House — the C.I.A.’s covert action chief, Richard Helms, brought J.F.K. what he termed “hard evidence” that Castro was still trying to foment revolution throughout Latin America.

Helms (who later served as C.I.A. director from 1966 to 1973) and an aide, Hershel Peake, told Kennedy about their agency’s discovery: a three-ton arms cache left by Cuban terrorists on a beach in Venezuela, along with blueprints for a plan to seize control of that country by stopping Venezuelan elections scheduled for 12 days hence.

Standing in the Cabinet Room near windows overlooking the darkened Rose Garden, Helms brandished what he called a “vicious-looking” rifle and told the president how its identifying Cuban seal had been sanded off.

Elie Abel wrote The Missile Crisis in 1966. In it Kennedy is quoted as saying after the crisis: “Any historian who walks through this minefield of charges and countercharges.”