American Lynching 2

1900 – 1921

In a previous post, Never Forget American Lynching, I gave an overview of lynching in the United States during the 19th century. This post will cover between 1900 and 1921.

As with the “Never Forget…” post, much of this information came from the Equal Justice Initiative‘s laborious research. Having said that, the article does not list every lynching from 1900 to 1921.

American Lynching 2

George H White

January 20, 1900: Black Congressman, George H White from North Carolina introduced the first bill in Congress to make lynching a federal crime to be prosecuted by federal courts; it died in committee, opposed by southern white Democrats.

American Lynching 2

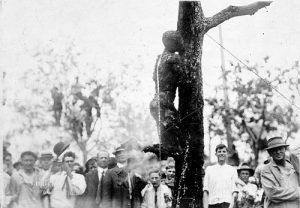

John Porter lynched

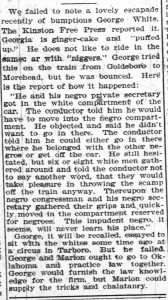

November 16, 1900: early in 1900 a black family, Preston Porter, Sr and his two sons, “John” and Arthur, moved to the Limon, Colorado area to work on the railroad.

On November 8, a white girl named Louise Frost was found dead in Limon. Newspapers reported that the Porters had left Limon for Denver a few days after the girl was found dead. White authorities focused suspicions on them.

On November 12th, authorities arrested all three and took them to the Denver jail. After four days, newspapers reported that sixteen-year-old Preston “John” Porter Jr had confessed to the crime “in order to save his father and brother from sharing the fate that he believes awaits him.”

Despite the Governor’s order that the risk of lynching was to great to return John to Limon, the Denver sheriff transported John there by train.

A mob of more than 300 white people from throughout Lincoln County awaited the train, removed Porter, and lynched him by chaining him to a railroad stake and burning him alive.

Newspapers described the lynching as follows:

John was said to have been reading a Bible and was allowed to pray before his lynching. When the flames reached his body, reports documented his screams for help as he writhed in pain, crying, “Oh my God, let me go men!…Please let me go. Oh, my God, my God!” When the ropes binding John to the stake had burned through, such that his body had fallen partially out of the fire, members of the mob threw additional kerosene oil over him and added wood to the fire. It was reported that John’s last words were “Oh, God, have mercy on these men, on the little girl and her father!”

No investigation into the lynching was conducted and the coroner concluded John died “at the hands of parties unknown.” [EJI article]

American Lynching 2

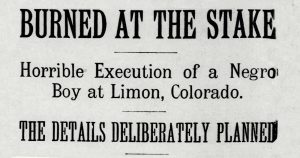

Ballie Crutchfield lynched

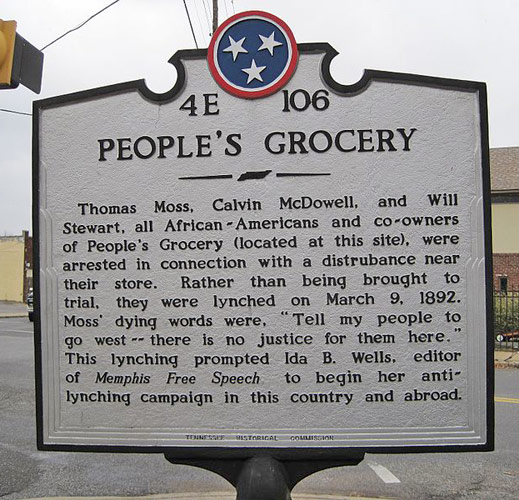

March 15, 1901: a white mob in Rome, Tennessee, lynched a Black woman named Ballie Crutchfield. Ms. Crutchfield was accused of no crime, and targeted simply because the mob had earlier that night failed in its attempt to lynch her brother.

A week earlier, a white man in Rome had reportedly lost a wallet containing $120. As word spread that a young Black boy had found the wallet and given it to a young Black man named William Crutchfield, white residents accused William of stealing the wallet.

Though there was no evidence supporting the claim that William Crutchfield had stolen the wallet, he was promptly arrested and taken to the local jail. That night, a white mob stormed the jail and abducted Mr. Crutchfield from police custody, but as they prepared to lynch him, he escaped.

The lynch mob searched but failed to find Mr. Crutchfield; determined to take out their vengeance on someone, they instead seized his sister, Ballie Crutchfield, from her home. Though she was not even alleged to be in any way involved with the lost wallet, the mob took Ms. Crutchfield—whose first name was also reported as “Sallie”—to a bridge a short distance from the town, tied her hands behind her back, shot her in the head, and threw her body into the creek below. [EJI article]

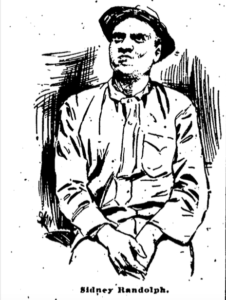

Silas Ester lynched

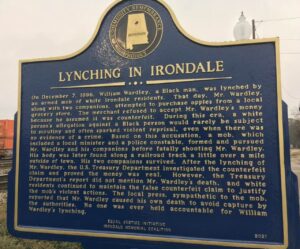

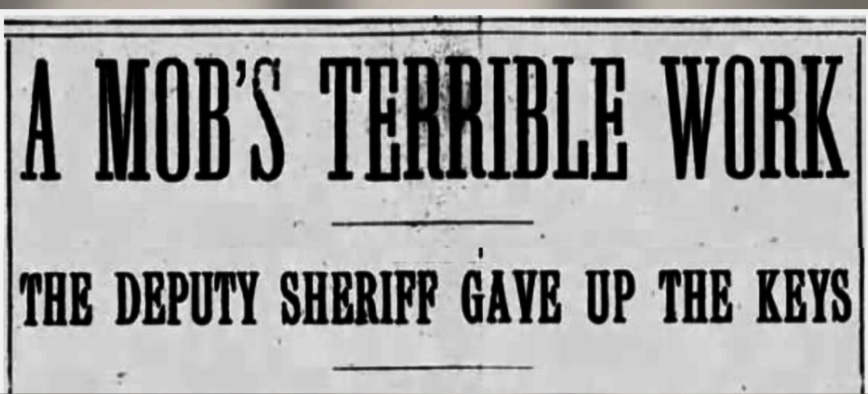

October 31, 1901: authorities in Hadgenville, Kentucky had arrested Silas Ester accusing him of coercing a young boy to commit a crime. At approximately 2:00 am a lynch mob of more than 50 white men tightened a noose around the neck Esters’s neck and dragged him from the LaRue County Jail.

Police officers at the jail had surrendered the keys and made no effort to protect Esters.

In an attempt to escape his fate, Mr. Esters slipped free and began to run away – but made it only 100 yards before his body was riddled with bullets. The mob then placed the rope noose around the neck of his corpse, dragged the lifeless body to the courthouse, and swung it from the top steps. No one was ever held accountable for the lynching of Silas Esters. [EJI article]

American Lynching 2

Thomas Brown lynched

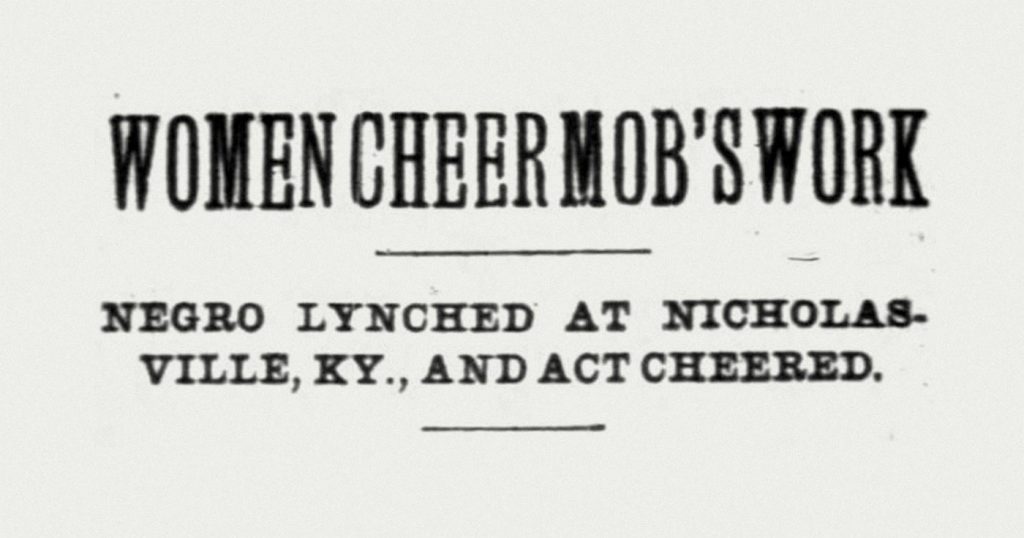

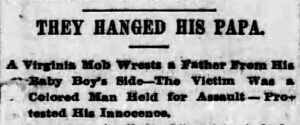

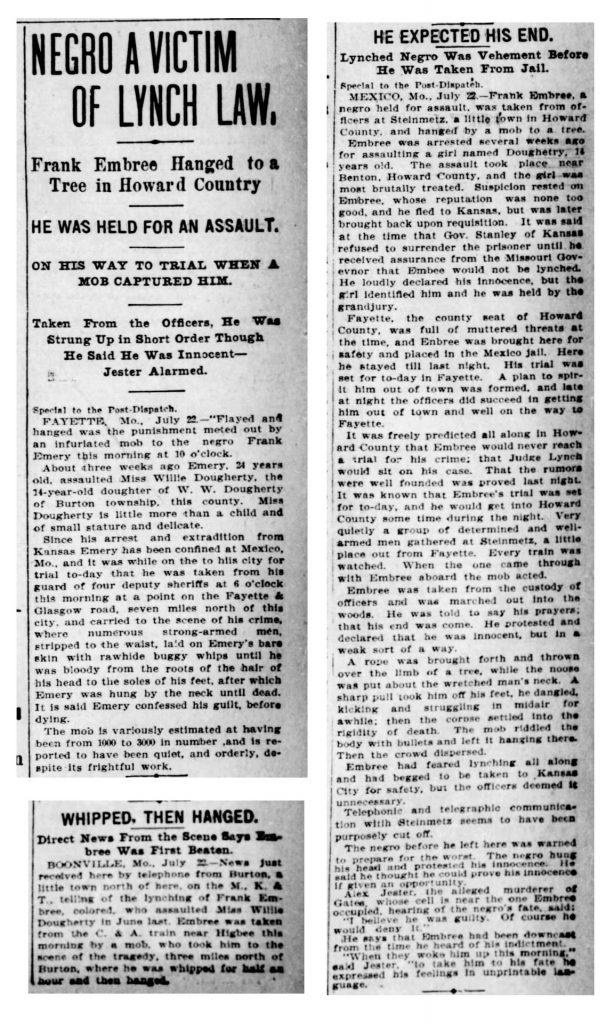

February 6, 1902: Thomas Brown, a 19-year-old black man, was seized from a jail cell and lynched on the lawn of the Jessamine County Courthouse in Nicholasville, Kentucky. Thomas had been arrested for an alleged assault on a white woman but never had the chance to stand trial.

A mob of 200 white men assembled at the jail and seized Thomas Brown from police. They then hung him from a tree in front of the county courthouse. Though news reports identified the young woman’s brother as a leader of the mob, no one was ever prosecuted for Thomas Brown’s murder and authorities concluded that he “met death by strangulation at the hands of parties unknown.” [EJI article]

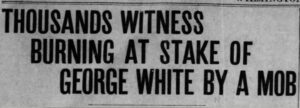

George White lynched

June 23, 1903: a white mob of more than 4,000 people in Wilmington, Delaware, burned a Black man named George White to death before he could stand trial. Mr. White, who had been arrested and accused of killing a young white woman, adamantly denied any involvement in the crime and never had the opportunity to defend himself in court.

Within one week of Mr. White’s arrest, two lynch mobs attempted to abduct him from the workhouse where he was being held. White Wilmington residents talked openly about these lynching plans. In a sermon on June 21, local white pastor Robert Elwood urged white residents to exact swift public vengeance by lynching Mr. White. A lynch mob began forming the next day, and its members spent the next two days meticulously planning the public spectacle lynching that took place on June 23. Despite this public planning, in which mob members even shared their plans in advance with police officers, authorities charged with protecting him did not relocate him to a different jail and the local court refused to advance his trial date. [EJI article]

American Lynching 2

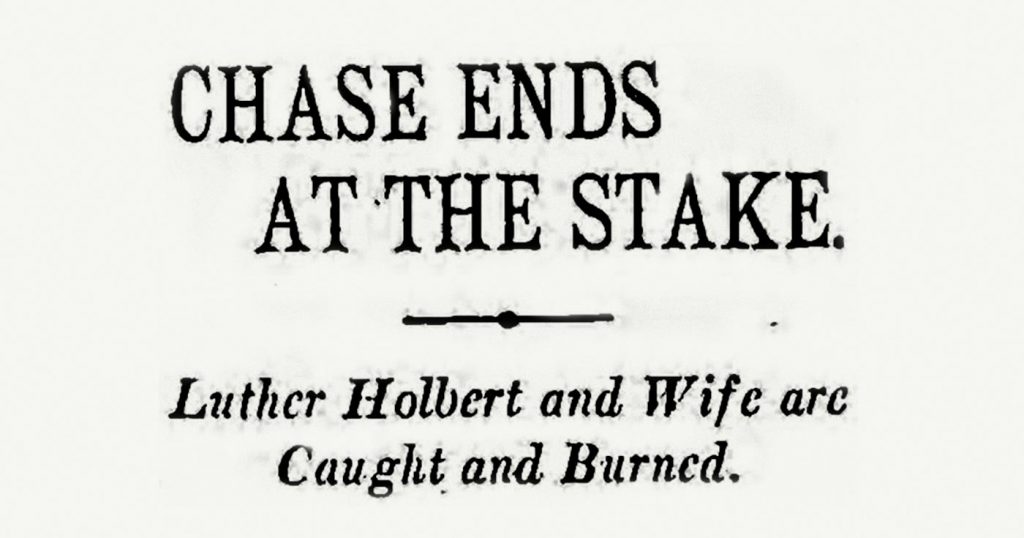

Luther Holbert & unidentified woman lynched

February 7, 1904: as hundreds of white people watched and cheered, a black man named Luther Holbert and an unidentified woman were tortured and killed in Doddsville, Mississippi, a Sunflower County town in the Mississippi Delta. Holbert was accused of shooting and killing James Eastland, a white landowner from a prominent, wealthy local family that owned a plantation where many of the area’s black laborers worked. After his shooting, James Eastland’s two brothers led the posse that captured Mr. Holbert and a black woman. Some news reports identified the woman as Mr. Holbert’s wife, but later research suggested she was not; her identity remains unknown.

According to an eyewitness account published in the Vicksburg, Mississippi, Evening Post, Luther Holbert and the unnamed black woman were tied to trees while their funeral pyres were prepared. They were then forced to hold out their hands and watch as their fingers were chopped off, one at a time, and distributed as souvenirs. Next, the same was done to their ears. Mr. Holbert was then beaten so badly that his skull was fractured and one of his eyes hung by a shred from the socket. The lynch mob next used a large corkscrew to bore into the arms, legs, and body of the two victims, pulling out large pieces of raw, quivering flesh. The victims reportedly did not cry out, and they were finally thrown on the fire and allowed to burn to death. The event was described as a festive atmosphere, in which the audience of 600 spectators enjoyed deviled eggs, lemonade, and whiskey. [EJI story]

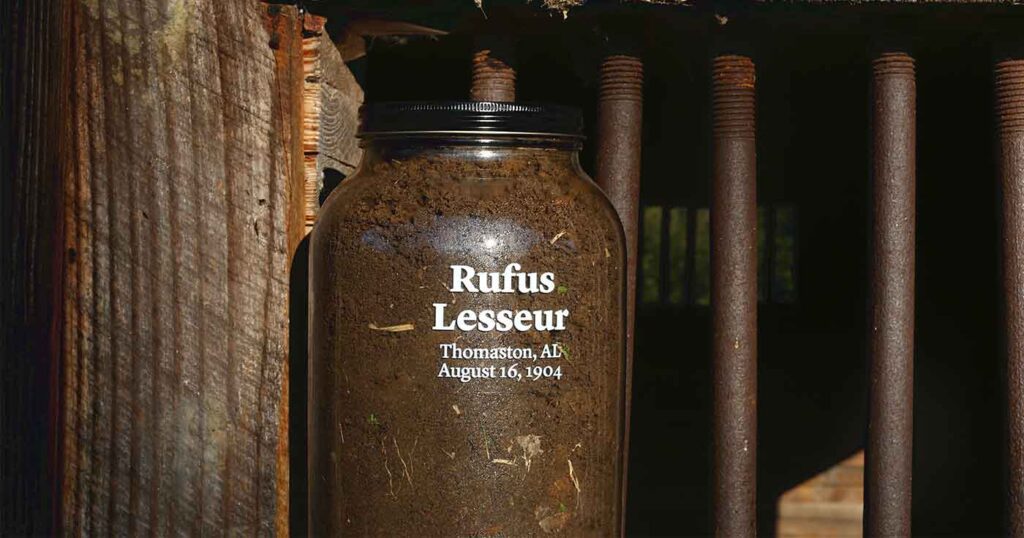

Rufus Lesseur lynched

August 16, 1904: a mob of unmasked white men in Marengo County, Alabama, lynched Rufus Lesseur, a 24-year-old Black man, and left his body riddled with bullets.

Less than two days earlier, a white woman in Thomaston, Alabama, claimed that a Black man had entered her home and frightened her. After someone claimed that a hat found near the woman’s home belonged to Mr. Lesseur, a mob of white men formed and kidnapped him. The white men transported a terrified Mr. Lesseur into the nearby woods, and locked him in a tiny calaboose, or makeshift jail for more than a day.

At 3:00 a.m. on August 16, without an investigation, trial, conviction of any offense, or a sentencing proceeding, a mob of white men broke into the locked shack, seized Mr. Lesseur, dragged him outside, and lynched him, filling his body with bullets.

Although he was lynched by a mob of unmasked white men in a town with only 300 residents, state officials claimed that no one could be identified, arrested, or prosecuted for his murder. [EJI article]

American Lynching 2

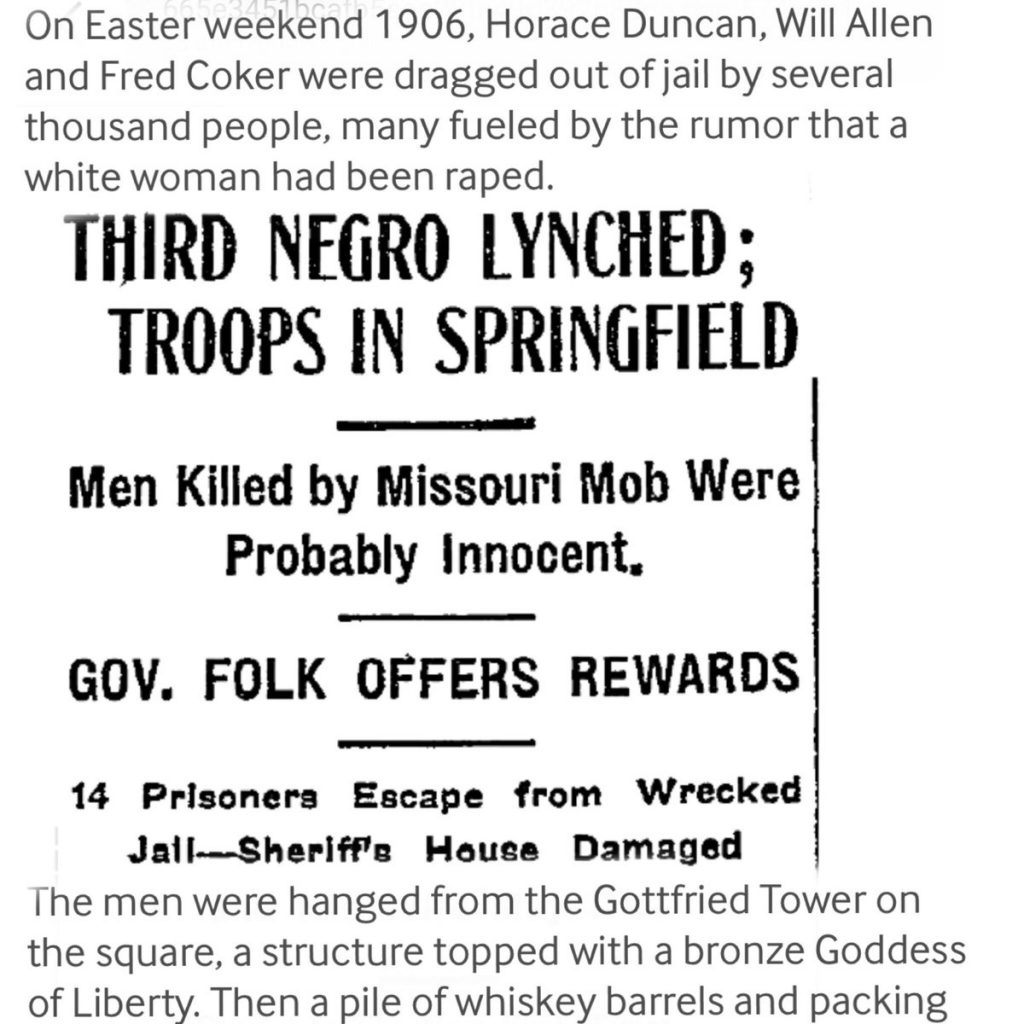

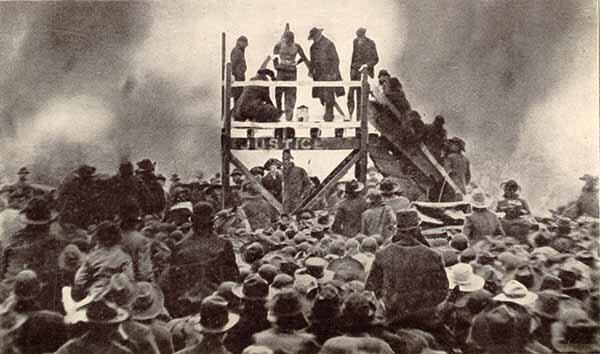

Horace Duncan, Fred Coker, and Will Allen lynched

April 14, 1906: two innocent black men named Horace Duncan and Fred Coker (aka Jim Copeland) were abducted from the county jail by a white mob of several thousand participants and lynched in Springfield, Missouri.

The day before, a white woman reported that two African American men had assaulted her. Despite having “no evidence against them,” local police arrested Duncan and Coker were “on suspicion.”

Local law enforcement did little to stop the mob from seizing the two men, though the officers were armed. When the mob dragged Duncan and Coker outside, the gathered crowd of nearly 3,000 angry white men, women, and children began shouting, “Hang them!” and “Burn them!”

At the public square, the mob hanged both men from the railing of the Gottfried Tower, then set a fire underneath and watched as both corpses were reduced to ashes in the flames.

Continuing their rampage, the mob returned to the jail and proceeded to lynch another African American man—Will Allen.

Two days after the lynchings, the woman who reported being assaulted issued a statement that she was “positive” that [Mr. Coker and Mr. Duncan] “were not her assailants, and that she could identify her assailants if they were brought before her.”

Four white men were arrested and twenty-five warrants issued, but only one white man was tried and no one was ever convicted. [EJI article]

American Lynching 2

1908

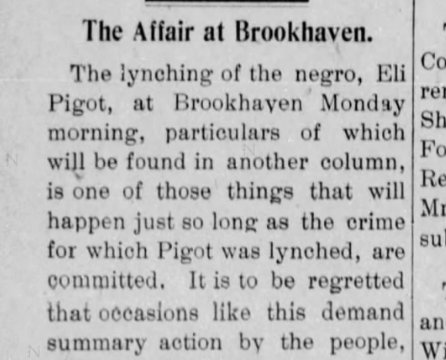

Eli Pigot lynched

February 10, 1908: a mob of more than 2,000 white people in Brookhaven, Mississippi lynched Eli Pigot, a black man, accused of assaulting a white woman.

According to news reports, police deputies and armed military guards transported Pigot from Jackson to Brookhaven to stand trial. Upon arrival in Brookhaven, the lynch mob briefly scuffled with the military guards before seizing him, kicking and beating him, and then hanging him from a telephone pole less than a hundred yards from the Lincoln County Courthouse. The mob then riddled Mr. Pigot’s corpse with bullets as it swung from the pole. [EJI article]

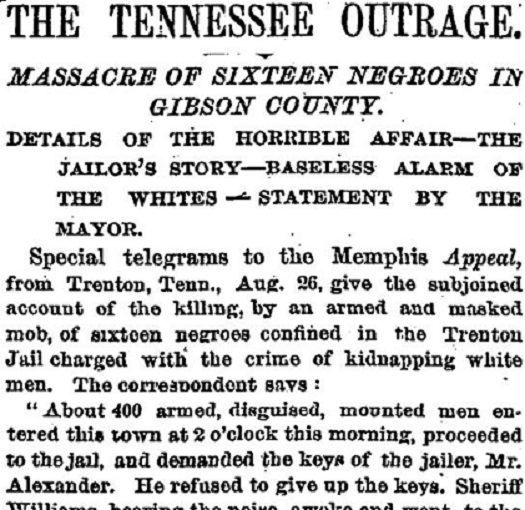

Nine Lynched in Sabine County, TX

June 22, 1908: nine Black men were lynched in Sabine County, Texas, within a 24-hour period. The reign of racial terror began when a white farmer was shot to death in his home by an unknown assailant on the evening of June 21.

Six Black men—Jerry Evans, William Johnson, William Manuel, Moses Spellman, Cleveland Williams, and Frank Williams—were already in jail, accused of being involved in a completely unrelated shooting of another local white man. Early on the morning of June 22, a mob of about 200 white men broke into the jail and seized them from the police custody. Five of the men were hanged from a tree outside of the jail, and Mr. Williams, the sixth, was shot in the back as he tried to escape.

Later that night, marauding white men shot and killed a Black man named Bill McCoy near the white farmer’s home, and shot and killed two unidentified Black men and threw their bodies into a creek. A Black church and school house in the town were also burned to the ground. [EJI article] (next BH and Lynching, see Aug 14 or see AL2 for expanding lynching chronology)

Springfield Lynchings

Day 1

August 14, 1908: a race revolt broke out in the Illinois capital of Springfield. Angry over reports that a black man had sexually assaulted a white woman, a white mob wanted to take a recently arrested suspect from the city jail and kill him. They also wanted Joe James, an out-of-town black who was accused of killing a white railroad engineer, Clergy Ballard, a month earlier.

Late that afternoon, a crowd gathered in front of the jail in the city’s downtown and demanded that the police hand over the two men to them. But the police had secretly taken the prisoners out the back door into a waiting automobile and out of town to safety. When the crowd discovered that the prisoners were gone, they rioted. First they attacked and destroyed a restaurant owned by a wealthy white citizen, Harry Loper, who had provided the automobile that the sheriff used to get the two men out of harm’s way. The crowd completed its work by setting fire to the automobile, which was parked in front of the restaurant.

The rioters next methodically destroyed a small black business district downtown, breaking windows and doors, stealing or destroying merchandise, and wrecking furniture and equipment. The mob’s third and last effort that night was to destroy a nearby poor black neighborhood called the Badlands. Most blacks had fled the city, but as the mob swept through the area, they captured and lynched a black barber, Scott Burton, who had stayed behind to protect his home. [Black Past article]

Day 2

August 15, 1908: at nightfall white rioters regrouped downtown. The new mob marched west to the state arsenal, hoping to get at several hundred blacks who had taken refuge there, but they were driven off by state troops who charged the crowd with bayonets fixed to their rifles. The crowd then marched to a predominantly white, middle-class neighborhood and seized and hung an elderly wealthy black resident. After this second killing, enough troops arrived in the capital to prevent further mass attacks. Nonetheless, what the press called “guerilla-style” hit-and-run attacks against black residents continued through August and into September.

American Lynching 2

NAACP formed

February 12, 1909: on the centennial of President Abraham Lincoln’s birth, African Americans signed a proclamation known as “The Call,” leading to the formation of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP). The interracial group was created to safeguard civil, legal, economic, human and political rights of African Americans.

The appeal took place in response to continued lynchings and the 1908 race riot in Springfield, Ill. Sixty people, including W. E. B. Du Bois, Ida B. Wells-Barnett and Mary Church Terrell, signed the proclamation.

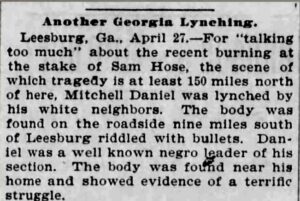

Douglas Lemon and Rankin Moore Lynched

June 5, 1910: a white mob lynched Douglas Lemon and Rankin Moore, two Black men, as they were walking home from a community festival in Orange County, Texas.

In the days leading up to the lynchings, white mobs had targeted and terrorized the Black community in Orange County, furious that a jury had recently failed to convict a Black man named Jack White of killing a white man. In addition to lynching Mr. Lemon and Mr. Moore, the white mob shot into the Black district of town and fired at other Black men, who managed to survive. No one was ever held accountable. [EJI article]

Norris Dendy Lynched

July 4, 1910: a white mob in Clinton, South Carolina, seized a 35-year-old Black man named Norris Dendy from a local jail cell, beat him, and hanged him. The mob then dumped Mr. Dendy’s brutalized body in a churchyard seven miles from Laurens County. Even though several Black people witnessed the mob seizing Mr. Dendy from the local jail, no one was ever held accountable. [EJI article]

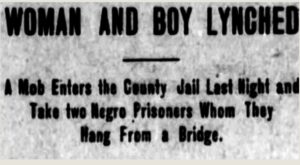

Laura Nelson & son L.D. Lynched

May 24, 1911: shortly before midnight, a mob of dozens of armed white men broke into the Okfuskee County jail in Okemah, Oklahoma, and abducted Laura Nelson and her young son, L.D. The mob took the Black woman and boy six miles away and hanged them from a bridge over the Canadian River, close to the Black part of town; according to some reports, members of the mob also raped Mrs. Nelson, who was about 28 years old according to census records, before lynching her alongside her son. Their bodies were found the next morning.

Hundreds of white people from Okemah came to view the bodies. Some even posed on the bridge to have their photos taken with the bodies of the dead Black woman and boy. Those photographs were later reprinted as postcards and sold at novelty stores.

When a special grand jury was called to investigate the lynching, the district judge instructed the white jurors to be mindful of their duty as members “of a superior race and greater intelligence to protect this weaker race.” No one was indicted, prosecuted, or held legally accountable for lynching Laura and L.D. Nelson. [EJI article]

Tom Allen and Joe Watts Lynched

June 27, 1911: a Walton County, Georgia mob of several hundred unmasked white men lynched two Black men named Tom Allen and Joe Watts after a local white judge—Charles H. Brand—had refused to allow state guardsmen to be present to prevent mob action.

Judge Brand had been aware of the threat of mob violence for weeks. Mr. Allen, who had been accused of assaulting a white woman, had been held in Atlanta for safekeeping because of the threat. In early June, Mr. Allen was brought to Monroe for trial with the protection of state troops from the Governor, but Judge Brand “resented” the presence of troops, postponed the trial because of the protection being offered, and sent Mr. Allen back to Atlanta. When Mr. Allen was ordered back to Monroe for trial on June 27, Judge Brand refused an offer of protection from the state troops. Consequently, Mr. Allen was protected only by two officers on the train.

Knowing that Mr. Allen no longer had the protection of state troops, the white mob intercepted the train bound for Monroe and seized Mr. Allen from the two officers charged with protecting him. The mob tied Mr. Allen to a telegraph pole and shot him while the passengers of the train and hundreds in the mob looked on.

The mob then proceeded to march six miles to the town jail where another Black man named Joe Watts was being held. Some newspapers reported that Mr. Watts was an alleged accomplice of Mr. Allen, while others noted Mr. Watts had been arrested for having “acted suspiciously” outside of a white man’s home, but had not been charged with a crime. The white mob stormed the jail without resistance from the jailers, removed Mr. Watts, and lynched him as well, hanging him to a tree and shooting him repeatedly. Both men had maintained that they were innocent, and contemporary newspapers reported that there was no evidence against them. [EJI article]

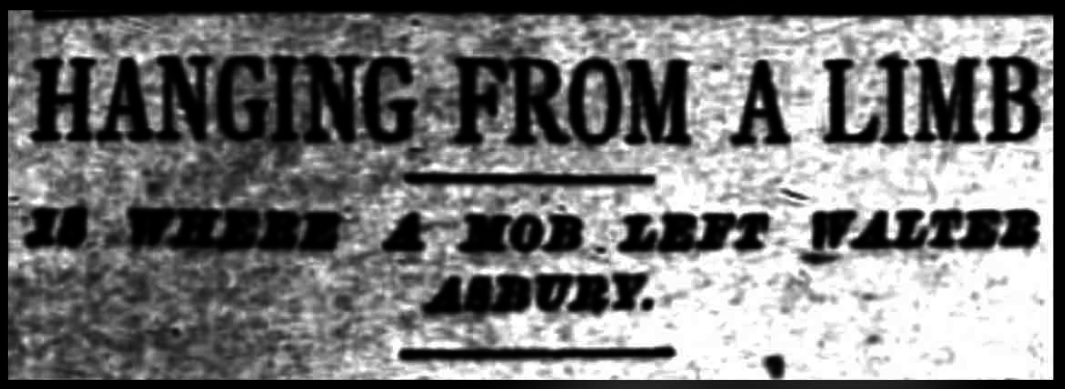

Walter Johnson lynched

September 5, 1912: a white mob in Princeton, West Virginia lynched a black man named Walter Johnson.

After Mr. Johnson was accused of assaulting a white girl, sheriff’s officials anticipated a lynch mob would form and moved him from Bluefield to Princeton. When the move was discovered, an armed mob of white men came to Princeton and seized Mr. Johnson. The local judge urged the mob to let the court conduct a “speedy trial,” and the state governor warned a lynching should not be allowed — but the mob was determined.

After kidnapping Mr. Johnson from police custody, the enraged mob beat Mr. Johnson with clubs and rocks, strung him to a telegraph pole “in the presence of the judge, sheriff, and armed guards” and shot him with hundreds of bullets. Despite their purported efforts to dissuade the mob, police did not attempt to use force to save Mr. Johnson’s life, and the judge did not order any members of the lynch mob arrested. [EJI article]

Rob Edwards lynched

September 10, 1912: a 24-year-old Black man named Rob Edwards was lynched and hung in downtown Cumming, Edwards was one of several Black men arrested on suspicion of involvement in the fatal assault of a young white woman named Mae Crow.

At least 2,000 white residents of Forsyth County formed a mob and stormed the jail. They found Edwards in his cell, brutally beat him with a crowbar, and shot him repeatedly. The mob then dragged Edwards through the streets to the town square, where they hung his mutilated body and left it on display. Subsequently, two Black teenagers who were also arrested for Mae Crow’s assault, Ernest Knox and Oscar Daniels, were convicted by all-white juries after trials that lasted one day each. They were hanged before thousands of white spectators.

Edwards’s lynching and the mob violence that followed terrorized the remaining 1,098 Black residents of Forsyth County, who fled the county in fear. The loss of Black-owned property in order to flee arbitrary mob violence was common during this era, and Forsyth’s Black residents left behind their homes and farms to escape, taking with them only what they could carry. Forsyth County would remain essentially all white until the 1990s.

No one was ever held accountable for Mr. Edwards’s lynching or the mass exodus of Black residents that followed. [EJI story] [video story]

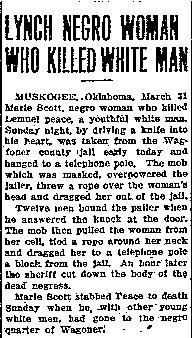

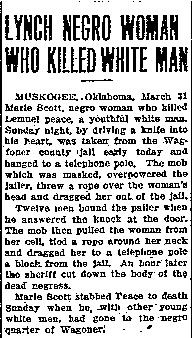

Marie Scott

March 31, 1914: a white lynch mob in Wagoner County, Oklahoma, seized a 17-year-old black teenaged girl named Marie Scott from the local jail, dragged her screaming from her cell, and hanged her from a nearby telephone pole. Days before, a young white man named Lemuel Pierce was stabbed to death while he and several other white men were in the city’s “colored section”; Marie was accused of being involved.

It is most likely that Scott (or her brother) was defending herself from a sexual assault by Pierce or others in the white group. [EJI article]

American Lynching 2

Marie Scott lynched

March 31, 1914: a white lynch mob in Wagoner County, Oklahoma, seized a 17-year-old black teenaged girl named Marie Scott from the local jail, dragged her screaming from her cell, and hanged her from a nearby telephone pole. Days before, a young white man named Lemuel Pierce was stabbed to death while he and several other white men were in the city’s “colored section”; Marie was accused of being involved.

It is most likely that Scott (or her brother) was defending herself from a sexual assault by Pierce or others in the white group. [EJI article]

Caesar Sheffield lynched

April 17, 1915: a mob of white men near Lake Park, Georgia took 17-year-old Black boy Caesar Sheffield from jail and shot him to death. Police had arrested Caesar for allegedly stealing meat from a smokehouse owned by a local white man.

When the mob took Caesar from the jail, prison officials had abandoned the building despite being charged with protecting those inside the jail, allowing the mob to easily force its way into the jail. The men took Caesar to a nearby field and shot him to death. His body was found later that day, riddled with bullets.

No arrests were made following his murder and no one was ever held accountable. [EJI article]

Cordelia Stevenson Raped/Lynched

December 8, 1915: a white mob in New Hope near Columbus, Mississippi, raped and lynched a Black woman named Cordelia Stevenson and left her body hanging for days near a railroad track to terrorize Black residents.

Though the local police had concluded the her son had not been involved in a barn fire months earlier and released Mrs Stevenson and her husband, on December 8, a white mob gathered outside the Stevenson home, forced their way into the house while the couple slept, and kidnapped Mrs. Stevenson. The mob raped and lynched her, then left Mrs. Stevenson’s naked, brutalized body hanging by the railroad track for two days, where she was visible to thousands of people traveling by train.

No one was ever held responsible for her death. [EJI article]

American Lynching 2

see Jesse Washington for much more

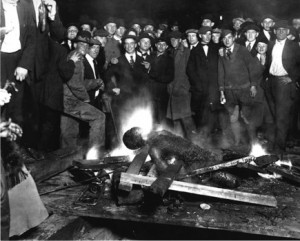

May 15, 1916: [From Equal Justice Initiative]: after an all-white jury convicted Jesse Washington of the murder of a white woman, he was taken from the courtroom and burned alive in front of a mob of 15,000.

When he was accused of killing his employer’s wife, seventeen-year-old Jesse Washington’ greatest fear was being brutally lynched – a common fate for black people accused of wrongdoing at that time, whether guilty or not. After he was promised protection against mob violence, Jesse, who suffered from intellectual disabilities, according to some reports, signed a statement confessing to the murder. On the morning of May 15, 1916, Washington was taken to court, convicted of murder, and sentenced to death in a matter of moments. Shortly before noon, spectators snatched him from the courtroom and dragged him outside, the “promise of protection” quickly forgotten.

The crowd that gathered to watch and/or participate in the brutal lynching grew to 15,000. Jesse Washington was chained to a car while members of the mob ripped off his clothes, cut off his ear, and castrated him. The angry mob dragged his body from the courthouse to City Hall and a fire was prepared while several assailants repeatedly stabbed him. When they tied Jesse Washington to the tree underneath the mayor’s window, the lynchers cut off his fingers to prevent him from trying to escape, then repeatedly lowered his lifeless body into the fire. At one point, a participant took a portion of Washington’s torso and dragged it through the streets of Waco. During the lynching, a professional photographer took photos which were later made into postcards.

Following news reports of the lynching, the NAACP hired a special investigator, Elizabeth Freeman. She was able to learn the names of the five mob leaders and also gathered evidence that local law enforcement had done nothing to prevent the lynching. Nevertheless, no one was ever prosecuted for their participation in the lynching of Jesse Washington.

After the lynching, the growing mob patrolled the town terrorizing other African Americans, threatening to lynch other black people they encountered – including those who attempted to cut down Mr. Johnson’s hanging corpse. Instead, the mob cut the dead body down, stripped off most of the clothing to keep as souvenirs, and then again hanged the corpse from the same pole.

According to press reports, authorities later acknowledged a growing possibility that Johnson had been wrongly identified and was innocent of the alleged assault. Nevertheless, a grand jury convened to investigate the murder declined to return a single indictment, and no one was ever arrested or prosecuted for his lynching.

Six Lynched

August 19, 1916: five Black individuals—Andrew McHenry, Bert Dennis, John Haskins, Mary Dennis and Stella Young—were lynched by a mob of white people in Alachua County, Florida, while a Black man named James Dennis was also killed nearby by a “sheriff’s posse.” On the same day, almost 1,000 miles away, in Navarro County, Texas, Edward Lang, a 21-year-old Black man was lynched by a mob of 200 white people.

On August 18, in Jonesville, Florida, a Black man by the name of Boisey Long was accused of murdering the local constable. When Mr. Long went missing, word spread that four Black men—Andrew McHenry, Bert Dennis, James Dennis, and John Haskins—and two Black women—Mary Dennis and Stella Young—had allegedly aided Mr. Long in an escape. On Saturday, August 19, a mob of white people captured Andrew McHenry, Bert Dennis, John Haskins, Mary Dennis, and Stella Young, and lynched them. According to reports, on the same day James Dennis was captured and killed by a “sheriff’s posse.”

Edward Lang was accused of assaulting a young white woman near the town of Rice in Navarro County, Texas. A mob of white people captured Mr. Lang four miles from where the alleged attack took place and handed him over to the sheriff. However, before Mr. Lang could be tried, on that same day, an unmasked and armed mob of 200 white farmers seized him from the jail, and hung Mr. Lang to a telephone pole. [EJI story]

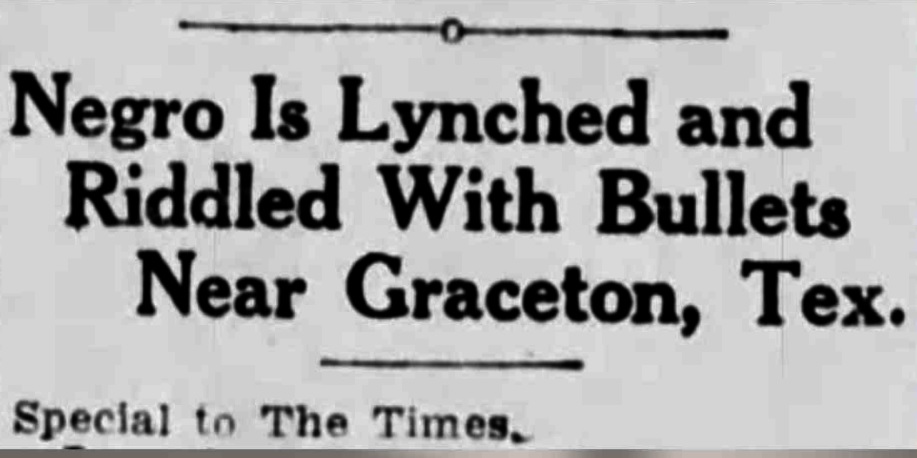

William Spencer lynched

October 4, 1916: William Spencer, a 30-year-old Black man and a husband and father of four children, was lynched by a white mob near Graceton, Texas. Mr. Spencer, who was a farmhand, had a confrontation with the constable and was arrested and taken to a local jail, where a white mob seized and lynched him. [EJI article]

American Lynching 2

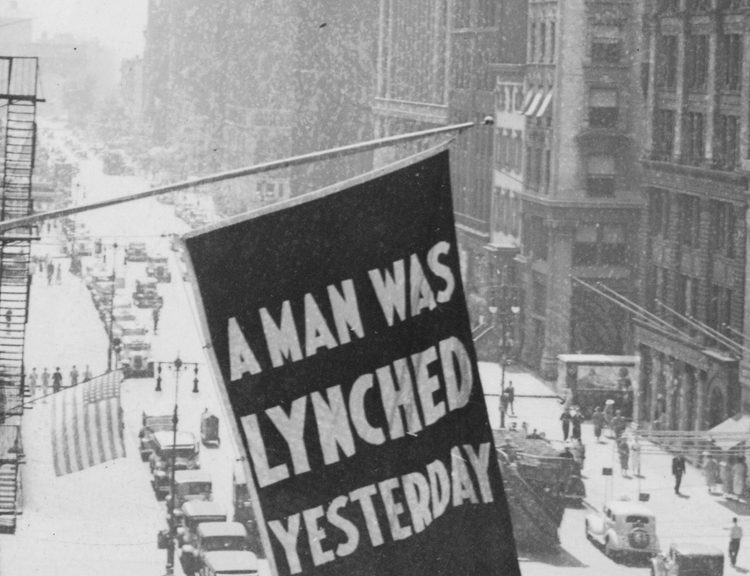

Silent protest

July 28, 1917: up to 10,000 African Americans silently paraded down New York City’s Fifth Avenue to protest lynchings in the South and race Revolts in the North. The NAACP and Harlem leaders organized the protest as the U.S. was going to fight “for democracy” in World War I. One parade banner read: “Mr. President, why not make America safe for democracy?” [HuffPost article]

American Lynching 2

Leonidas C Dyer

In April 1918: Congressman Leonidas C. Dyer (R-Missouri) introduced an anti-lynching bill in the House of Representatives, based on a bill drafted by NAACP founder Albert E. Pillsbury in 1901. The bill called for the prosecution of lynchers in federal court. State officials who failed to protect lynching victims or prosecute lynchers could face five years in prison and a $5,000 fine. The victim’s heirs could recover up to $10,000 from the county where the crime occurred. (Bio Guide dot Congress bio)

American Lynching 2

Hayes Turner lynched

May 18, 1918: Hampton Smith was a farmer in Valdosta, Georgia. He often He found labor by paying fines and then forcing the person to work on his farm. He was notorious for abusing those workers. On May 16, someone killed him. A Sidney Johnson was a suspect. During the manhunt for Johnson, at least 13 people were killed. Among those killed was Hayes Turner, who was seized from custody after his arrest on the morning of May 18, 1918, and lynched. [Black Then article]

Mary Turner Lynched

May 19, 1918: Mary Turner the 8-month pregnant wife of Hayes Turner, publicly denounced her husband’s lynching the previous day. A mob hung her upside down from a tree, doused her in gasoline and motor oil, and set her on fire. While Turner was still alive, a member of the mob split her abdomen open with a knife. Her unborn child fell on the ground, where it cried before it was stomped on and crushed. Finally, Turner’s body was riddled with hundreds of bullets. Mary Turner and her child were cut down and buried near the tree. A whiskey bottle marked the grave. No charges were ever brought against the known or suspected participants in these crimes. [Miami Herald article]

American Lynching 2

Lynchings protest

July 29, 1918: in response to the increase of racially motivated killings (83 lynchings were recorded in 1918 alone), the National Liberty Congress of Colored Americans asked Congress to make lynching a federal crime. Despite attempts over the next several decades, anti-lynching legislation never passed. (Black In Time article)

Omaha, Nebraska race revolt

September 28, 1919: a major race riot erupted in Omaha, Nebraska. A white mob of about 4,000 people lynched and burned the body of Willie Brown, an African-American who was being held in the county jail. The mayor of Omaha, who was white, was almost lynched by the mob, which set fire to the county courthouse.

The origin of the revolt lay in racial conflict in the extensive city stockyards and meat packing plants. (A similar conflict underlay the East St. Louis race revolt that began on July 2, 1917.) Rumors that Willie Brown had raped a white woman spurred the lynching. Later reports by the police and U.S. Army investigators determined that the victim had not made a positive identification. The riot lasted for two days, and ended when over 1,200 federal troops arrived to restore order. Although martial law was not formally proclaimed, for all practical purposes it existed, with troops remaining in the city for several weeks. [Black Past article]

American Lynching 2

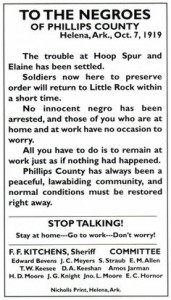

Elaine, Arkansas lynchings

Day 1

September 30, 1919: Black farmers met in Elaine, Ark., to establish the Progressive Farmers and Householders Union to fight for better pay and higher cotton prices.

White mobs descended on the black town destroying homes and businesses and attacking anyone in their path. Terrified black residents, including women, children, and the elderly, fled their homes and hid for their lives in nearby woods and fields. A responding federal troop regiment claimed only two black people were killed but many reports challenged the white soldiers’ credibility and accused them of participating in the massacre. Today, historians estimate hundreds of black people were killed in the massacre. .

When the violence was quelled, sixty-seven black people were arrested and charged with inciting violence, while dozens more faced other charges. No white attackers were prosecuted, but twelve black union members convicted of riot-related charges were sentenced to death. The NAACP represented the men on appeal and successfully obtained reversals of all of their death sentences.

Day 2

October 1, 1919: a race riot broke out in Elaine, Arkansas. Black sharecroppers were meeting in the local chapter of the Progressive Farmers and Household Union of America. Planters opposed their efforts to organize for better terms and the sharecroppers had been warned of trouble. A white man intent on arresting a black bootlegger approached the lookouts defending the meeting, and was shot. The planters formed a militia to attack the African-American farmers. In the ensuing riot they killed between 100 and 200 blacks, and five whites also died. [Black Past article]

American Lynching 2

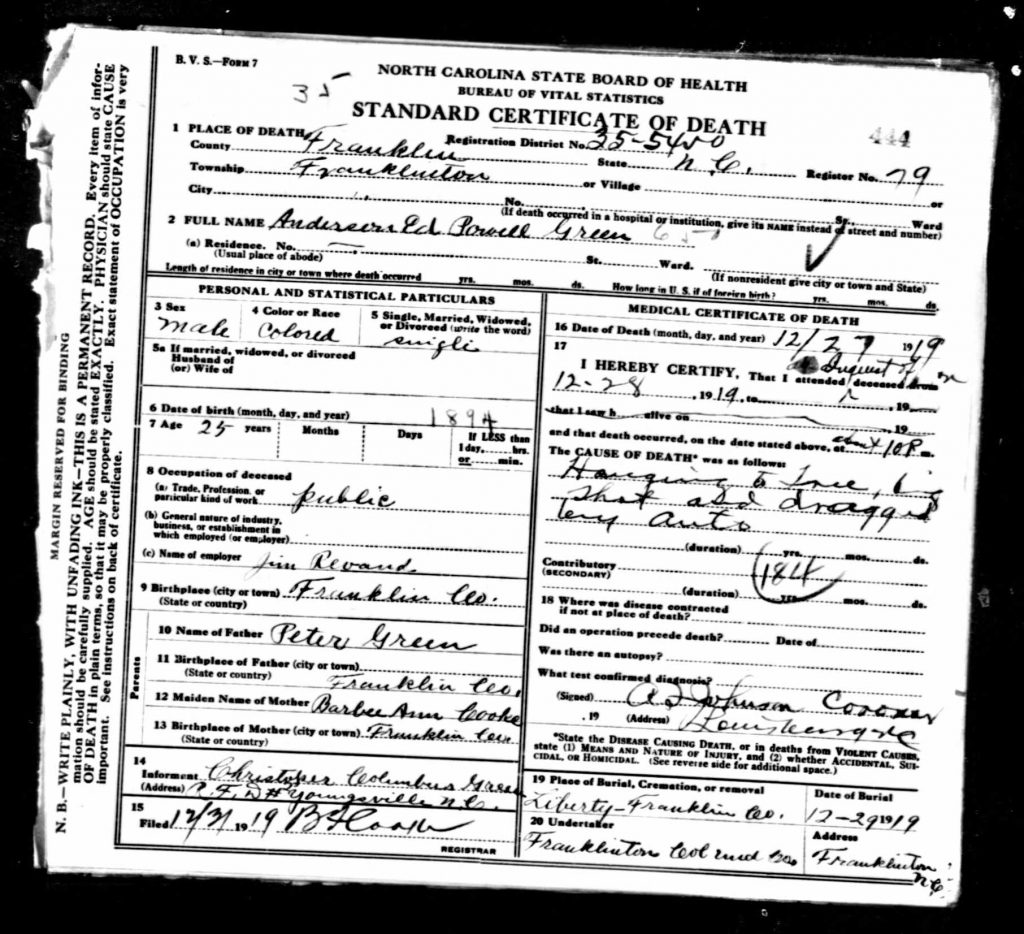

Powell Green lynched

December 27, 1919: after a “prominent” white movie theater owner was shot and killed, authorities arrested 23-year-old African American veteran Powell Green for allegedly committing the crime. While policemen were moving Powell Green from the jail in Franklinton, North Carolina to the larger city of Raleigh, before he could be tried or mount a defense, a mob kidnapped and brutally killed him.

The mob tied Green to a car and dragged him for half a mile before shooting him with dozens of bullets and hanging his body

Newspaper sources suggest this was the case in the lynching of Powell Green; one witness reportedly testified that, though there were five officers in the police vehicle transporting Mr. Green, he was “taken from the car [by the mob] without the least trouble.”

Green’s corpse was found the next morning riddled with bullets and hanged from a small pine tree along a road two miles from Franklinton. According to press accounts, “souvenir hunters” cut buttons and pieces of clothing from the body and later cut down the tree to yield grotesque keepsakes. [EJI article]

American Lynching 2

Duluth, Minnesota lynching

June 15, 1920: a mob in Duluth, Minnesota attacked and lynched three African American circus workers. Rumors had circulated that six African Americans had raped and robbed a teenage girl. A physician’s examination subsequently found no evidence of rape or assault. [Minnesota Historical Society article]

American Lynching 2

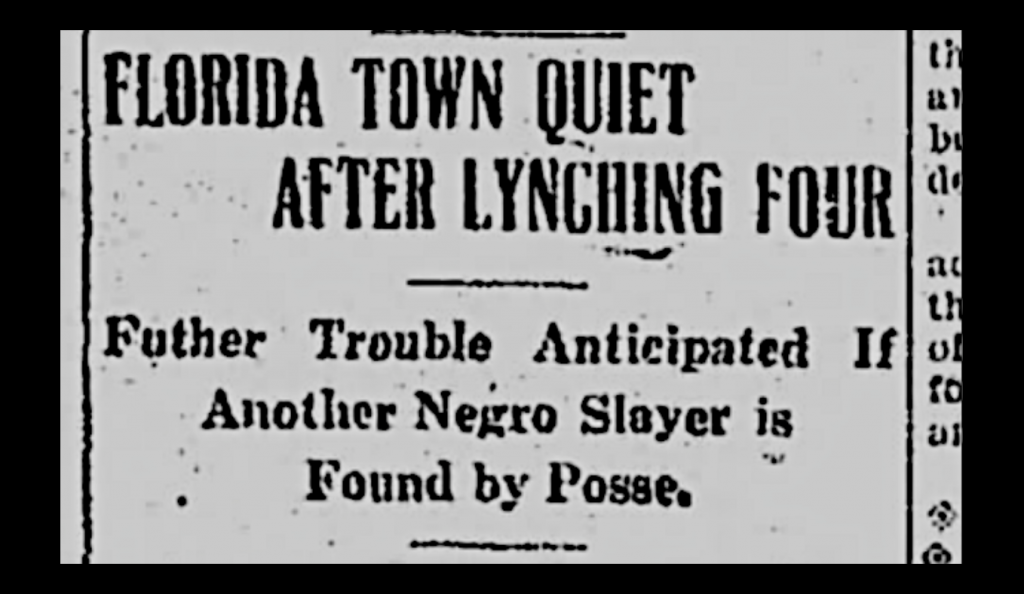

White terrorist vigilantism

October 5, 1920: four black men were killed in Macclenny, Florida, following the death of a prominent young white local farmer named John Harvey. According to news reports at the time, Harvey was shot and killed at a turpentine camp near MacClenny on October 4, 1920. The suspected shooter, a young black man named Jim Givens, fled immediately afterward and mobs of armed white men formed to pursue him. Givens’s brother and two other black men connected to him were questioned and jailed during the search, though there was no evidence or accusation that they had been involved in the killing of Harvey.

Those three men – Fulton Smith, Ray Field, and Ben Givens – were held in the Baker County Jail late into the night until, around 1:00 a.m. on October 5, a mob of about 50 white men overtook the jail and seized the men from their cells. The mob forced the men to the outskirts of town, where they were tied to trees and shot to death. A fourth lynching victim, Sam Duncan, was found shot to death nearby later in the day. Also with no alleged ties to the killing of John Harvey, Duncan was thought to be an unfortunate soul who had encountered a mob seeking Jim Givens and been killed simply for being a black man.

Three days later, the Chicago Defender, a Northern black newspaper, reported that most of the black community of Macclenny had deserted the area in fear of further violent attacks while whites posses continued to search for Jim Givens. [EJI article]

Ocoee Election Day Massacre

November 2, 1920: white mobs in Ocoee, Florida, began a campaign of terror and violence, designed to stop Black citizens in Ocoee from voting, that resulted in the deaths of dozens of Black people and the destruction of the Black community.

Over a two-day span, a mob of white Floridians killed dozens of Black people, burned 25 Black homes, two Black churches, and a masonic lodge in Ocoee. Estimates of the total number of Black Americans killed during the violence range from six to over 30. Because neither the government nor the newspapers at the time thought it was important to establish how many Black people were killed during this attack, we will never have an adequate accounting of this violence. [EJI article]

Wade Thomas Lynched

December 26, 1920: Wade Thomas was a native of Jonesboro County, Arkansas. On Christmas night 1920, Thomas was armed with a pistol and was playing a game of craps with his neighborhood black friends. Police officer Elmer “Snookums” Ragland raided the game, and shots were fired. Ragland was killed and Thomas was injured. Thomas escaped to the next county but was arrested there and brought back to Jonesboro County.

A coroner’s jury indicted Thomas for murder. Allegedly, Thomas confessed to killing Policeman Ragland, but claimed that he did not shoot until after he had been wounded twice. An angry mob stormed the court and told the judge to leave unless he wanted to witness the lynching. After Thomas was taken from his jail cell, a noose was draped around his neck and he was led to a telephone pole and hung. [BlackThen article]

American Lynching 2

1921

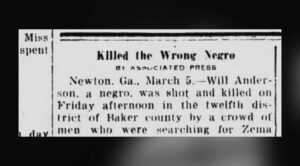

William Anderson lynched

March 4, 1921: a white mob in Baker County, Georgia searching the area to find and lynch a Black man named Zema Anthony came upon a Black man named William Anderson walking down the road and lynched him instead.

Two days before, allegations had spread that Mr. Anthony had killed a white sheriff and shot another white man in the town of Newton, Georgia. Without investigation or trial, a mob of white men intent on lynching him gathered and began searching the county with no success. After more than a day of the fruitless manhunt, the heavily armed white mob confronted Anderson as he was simply walking down the road. Terrified, Anderson ran from the mob and the white men quickly shot him to death.

Shortly after Anderson was killed, the body of his aunt was reportedly found floating in a stream. At least one newspaper reported that the same lynch mob had likely killed the Black woman for allegedly harboring Mr. Anthony and helping him to avoid capture. The press coverage did not report her name. [EJI article] (next BH & next Lynching, see Apr 5, or for for expanded chronology, see American Lynching 2)

Peons

April 5, 1921: although the 13th Amendment to the Constitution abolished slavery, African Americans continued to be held as de facto slaves in systems of peonage, a form of debt bondage. “Peons” or indentured servants owed money to their “masters” and were forced to work off their debt, a process that took years. A federal law passed in 1867 prohibited peonage but the practice continued for decades throughout the South. It was notoriously difficult to prosecute those who violated the federal law and those who were prosecuted were often acquitted by sympathetic juries.

Fear of a peonage prosecution led to a brutal spree of murders in rural Georgia in 1921. John Williams, a local white plantation owner, held blacks on his farm against their will in horrific, slavery-like conditions. After federal investigators suspected that Williams was violating the peonage law, Williams decided to get rid of the “evidence” of his crime by killing eleven black men whom he had been working as peons. Williams’s trial began on April 5, 1921, and four days later he was convicted of murder and sentenced to life imprisonment. He died in prison several years later.

Following the murders by Williams and other local atrocities against black people, Georgia Governor Hugh Dorsey in 1921 released a pamphlet entitled “A Statement from Governor Hugh M. Dorsey as to the Negro in Georgia.” Dorsey had collected 135 cases of mistreatment of blacks in the previous two years, including lynchings, extensive peonage, and general hostility. Dorsey recommended several remedies, including compulsory education for both races; a state commission to investigate lynchings; and penalties for counties where lynchings occurred. Reflecting on the mob violence that had become common throughout the South, Dorsey wrote, “To me it seems that we stand indicted as a people before the world.”

In response, several officials denied the charges contained in the pamphlet and many Georgians called for Dorsey’s impeachment.

American Lynching 2

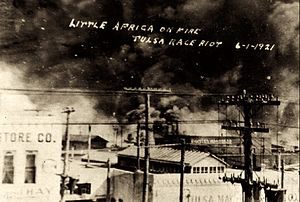

Tulsa Race Riot

May 31 and June 1, 1921: The Tulsa Race Riot was a large-scale racially motivated conflict in which whites attacked the Tulsa, Oklahoma black community of the Greenwood District, also known as ‘the Black Wall Street’ and the wealthiest African-American community in the United States, being burned to the ground. During the 16 hours of the assault, over 800 people were admitted to local hospitals with injuries, and more than 6,000 Greenwood residents were arrested and detained. An estimated 10,000 blacks were left homeless, and 35 city blocks composed of 1,256 residences were destroyed by fire.

For previous and subsequent chronologies, see…

- Never Forget American Lynching

- American Lynching 3

- American Lynching 4

- also see Dyer Anti-Lynching Bill