Greensboro 4 Desegregate Lunch Counters

Sit ins

When Joseph McNeil, Franklin McCain, Ezell Blair, Jr. and David Richmond sat down at the F.W. Woolworth store in Greensboro, N.C, they were continuing a non-violent strategy that other had used before them. Here is a chronology of these brave people, their story, their influence, and their successes.

The majority of the data for this chronology came from the Sit In Movement dot org site)

Greensboro 4 Desegregate Lunch Counters

Greensboro Four

February 1, 1960: Joseph McNeil, Franklin McCain, Ezell Blair, Jr. and David Richmond (The Greensboro Four) entered the F.W. Woolworth store in Greensboro, N.C., around 4:30 p.m. and purchased merchandise at several counters. (Independent Lens bios of the Greensboro Four)

They sat down at the store’s “whites only” lunch counter and ordered coffee, and were ignored and then asked to leave. They remained seated at the counter until the store closed early at 5 p.m. The four friends immediately returned to campus and recruited others for the cause.

Greensboro 4 Desegregate Lunch Counters

Greensboro 29

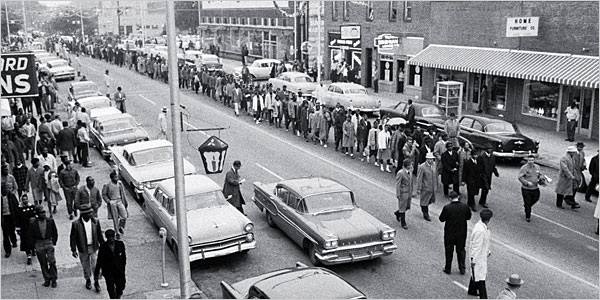

February 2, 1960: twenty-five men, including the four freshmen, along with four women returned to the F.W. Woolworth store. The students sat from 11 a.m. to 3 p.m. while white patrons heckled them. Undaunted, they sat with books and study materials to keep them busy. They were still refused service.

Reporters from both newspapers, a TV camera man and Greensboro police officers monitored the scene. Once the sit-ins hit the news, momentum picked up and students across the community embraced the movement.

Greensboro 4 Desegregate Lunch Counters

Student Executive Committee for Justice

That night, students met with college officials and concerned citizens. They organized the Student Executive Committee for Justice to plan the continued demonstrations. This committee sent a letter to the president of F.W. Woolworth in New York requesting that his company “take a firm stand to eliminate discrimination”. Meanwhile, at its regular monthly meeting, the NAACP voted in unanimous support of the students’ efforts.

February 3, 1960: more than 60 students, one-third of them female, returned to the Greensboro store and sat down at every available lunch counter seat. Students from Bennett College and Dudley High School increased the number of protesters, and many carpooled to and from the F.W. Woolworth store to sit-in shifts.

Greensboro 4 Desegregate Lunch Counters

“Local custom“

Members of the Ku Klux Klan, including the state’s official chaplain George Dorsett, were present. White patrons taunted the students as they studied. A statement issued from F.W. Woolworth’s national headquarters read that company policy was “to abide by local custom.”

February 4, 1960: more than 300 students participated in the protests. Students from N.C. A & T, Bennett College, and Dudley High School occupied every seat at the lunch counter. Three white supporters (Genie Seaman, Marilyn Lott and Ann Dearsley) from the Woman’s College of the University of North Carolina (now UNCG), joined the protest.

As tensions grew, police kept the crowd in check. Waiting students then marched to the basement lunch counter at S.H. Kress & Co., the second store targeted by the Student Executive Committee, and the Greensboro sit-ins spread.

That evening, student leaders, college administrators and representatives from F.W. Woolworth and Kress stores held talks. The stores refused to integrate as long as other downtown facilities remained segregated. Students insisted the F.W. Woolworth and Kress retail stores would remain targets, and the meeting ended without resolution.

Greensboro 4 Desegregate Lunch Counters

Tensions mount

February 5, 1960: tensions mounted early in the day when 50 white males were seated at the Woolworth counter. Sit-in participants, including white students from area colleges, filled the dozen or so remaining seats. Police removed two white youth from the store for swearing and yelling. By 3 p.m., more than 300 people were present. Members of both races were escorted from the premises. Three whites were arrested and the store closed at 5:30 pm.

Store representatives, students and college officials met once again that evening. F.W. Woolworth personnel took issue with the students limiting their protests to two stores and asked college administrators to end the sit-ins. Administrators plainly stated they could not control the private activities of students. Some administrators recommended store officials consider temporarily closing the counters. The meeting adjourned after two hours of debate.

February 6, 1960: early that morning, more than 1,400 N.C. A & T students met in Harrison Auditorium. After voting to continue the protest, many headed to the F.W. Woolworth store. They filled every seat as the store opened. A large number of counter protesters showed up as well. By noon, more than 1,000 people packed the store.

Greensboro 4 Desegregate Lunch Counters

Bomb threat

At 1 p.m., a caller warned a bomb was set to explode at 1:30 p.m. The crowd moved to the Kress store, which immediately closed. Arrests were made outside both stores. The F.W. Woolworth store was cleared and closed as the the manager announced the temporary closing of the lunch counter in the interest of public safety.

That evening at N.C. A&T, a mass rally of 1,600 students voted to suspend demonstrations for two weeks. Dean William Gamble proclaimed this would give the stores time “to set policies regarding food service for Negro students.”

Greensboro 4 Desegregate Lunch Counters

Sit ins expand

February 8 – 14 1960: students in Winston-Salem, N.C., and Durham, N.C., held sit-ins to demonstrate their solidarity with Greensboro students. Sit-in protests quickly followed in North Carolina cities such as Charlotte, Raleigh, Fayetteville and High Point. The movement also gained momentum and spread to Florida, South Carolina, Tennessee, Virginia and even F.W. Woolworth stores in New York City.

February 13, 1960: led by Diane Nash and James Bevel, and inspired by Rev. James Lawson’s philosophy of nonviolence, 100 African-American students from Fisk University and Tennessee A & I University (now Tennessee State University) began a sit-in to desegregate public facilities in Nashville. (Tennessean article on Nash)

February 13, 1960: led by Diane Nash and James Bevel, and inspired by Rev. James Lawson’s philosophy of nonviolence, 100 African-American students from Fisk University and Tennessee A & I University (now Tennessee State University) began a sit-in to desegregate public facilities in Nashville. (Tennessean article on Nash)

February 15 – 21, 1960: Edward R. Zane, a member of the Greensboro City Council, worked with students to reach a compromise. The Mayor agreed to appoint a committee to address the issue, and the protestors agreed to continue negotiations. Several Greensboro associations, including The Board of Directors of the Greensboro Council of Church Women, the YWCA and several ministerial alliances came out in favor of integration.

Greensboro 4 Desegregate Lunch Counters

Richmond sit in

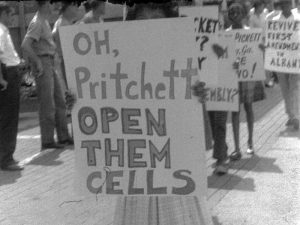

February 22, 1960: about 200 students, led by Frank George Pinkston and Charles Melvin Sherrod, marched from the Virginia Union University campus to downtown Richmond, shutting down the shopping district. Police arrested 34 students taking part in sit-ins and pickets at Thalhimer’s Department Store.

Greensboro 4 Desegregate Lunch Counters

Greensboro Advisory Committee

February 22 – 28, 1960: the lunch counters at F.W. Woolworth and Kress stores reopened, but were still segregated. Greensboro Mayor George H. Roach introduced the Greensboro Advisory Committee on Community Relations representing the City Council, the Chamber of Commerce and the Merchants Association. Chairman Ed Zane worked to increase public support for integration of lunch counters, encouraging people to write and express their opinions on the racial situation.

By the end of February, the sit-in movement had spread to more than 30 cities in eight states.

Greensboro 4 Desegregate Lunch Counters

Montgomery sit in

February 25, 1960: six students at the Alabama State College for Negroes, a state operated institution of higher learning for prospective Negro school teachers. along with 20 other students entered a publicly owned lunch grill in the basement of the courthouse in Montgomery, and asked to be served. Service was refused and the lunchroom was closed. “The Negroes refused to leave,” and police were called.

February 29, 1960: Alabama Governor John Patterson held a news conference to condemn the sit-in by the six Alabama State College students. Patterson, who was also chairman of the State Board of Education, threatened to terminate Alabama State College’s funding unless it expelled the student organizers and warned that “someone [was] likely to be killed” if the protests continued.

March 1, 1960: over 1000 people marched from the Alabama State College campus to the state capital and back. After this march, the president of the university expelled 9 students identified as leaders and suspended 20 other students, under pressure from the governor’s office. As a result of this, students at the college voted to boycott classes and exams.

March 2, 1960: Alabama State College expelled the nine student leaders of the March 1 courthouse sit-in.

More than 1000 students immediately pledged a mass strike, threatened to withdraw from the school, and staged days of demonstrations; 37 students were arrested. Montgomery Police Commissioner L.B. Sullivan recommended closing the college, which he claimed produced only “graduates of hate and racial bitterness.” Meanwhile, six of the nine expelled students sought reinstatement through a federal lawsuit.

Greensboro 4 Desegregate Lunch Counters

Felton Turner

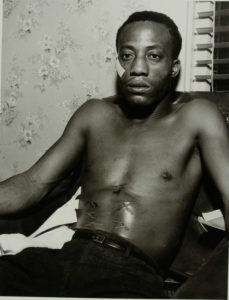

March 7, 1960: in reaction to sit-ins, 18-year-old Ronald Erickson abducted by Felton Turner of Houston beat him, and hung him by his knees upside down in a tree, after carving the initials KKK on Turner’s chest. Turner survived and escaped.

March 7, 1960: in reaction to sit-ins, 18-year-old Ronald Erickson abducted by Felton Turner of Houston beat him, and hung him by his knees upside down in a tree, after carving the initials KKK on Turner’s chest. Turner survived and escaped.

Greensboro 4 Desegregate Lunch Counters

Atlanta sit in

March 15, 1960: Julian Bond, civil rights activist and future Georgia state senator, led more than 200 Atlanta area students in the first sit-in protest in Atlanta, challenging segregated public accommodations. They presented “An Appeal for Human Rights” to city officials. (Today in Civil Rights site article)

Greensboro Advisory Committee

March 31, 1960: of the 2,000 citizen letters the Advisory Committee received, 73 percent favored integrated lunch counters. The hotly debated topic was constantly in the news. The Greensboro Record reported a letter signed by 68 white citizens urged that “service to all customers at the lunch counters in these stores be entirely on a ‘first come, first served’ basis, just as it is in other areas of these establishments.” Chairman Zane and the Advisory Committee held numerous meetings with representatives from F.W. Woolworth, Kress and other downtown businesses. All refused to integrate. On March 31, a disappointed Edward Zane met with student leaders to break the news.

By the end of March, the sit-in Movement had spread to 55 cities in 13 states.

Greensboro sit-ins continue

April 1, 1960: students resumed sit-in activities at the Kress and F.W. Woolworth stores and began picketing on Elm and Sycamore streets. That evening at a mass meeting, more than 1,200 students pledged to continue the protests.

April 2, 1960: both the F.W. Woolworth and Kress stores officially closed their lunch counters.

Greensboro 4 Desegregate Lunch Counters

Thurgood Marshall

April 3, 1960: speaking at Bennett College, NAACP legal council Thurgood Marshall urged attendees not to compromise. The protests strengthened after local leaders organized an economic boycott of the two stores.

April 3, 1960: speaking at Bennett College, NAACP legal council Thurgood Marshall urged attendees not to compromise. The protests strengthened after local leaders organized an economic boycott of the two stores.

Greensboro 4 Desegregate Lunch Counters

SNCC forms

April 16 – 17, 1960: Easter weekend, the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC) organized a meeting of sit-in students from all over the nation at Shaw University in Raleigh, N.C. Leader Ella Baker encouraged students to form the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC, pronounced “snick”) to organize the effort.

SNCC helped coordinate sit-ins and other direct action. From their ranks came many of today’s leaders, including Congressman John Lewis and longtime NAACP leader Julian Bond. At the conference, Guy Carawan sang a new version of “We Shall Overcome,” which became the national anthem of the civil rights movement. Workers joined hands and gently swayed in time, singing “black and white together,” repeating, “Deep in my heart, I do believe, we shall overcome some day.”

Greensboro 4 Desegregate Lunch Counters

Nashville bombing

April 19, 1960: terrorists bomb the home of Z. Alexander Looby, a Nashville civil rights lawyer who defended students arrested in Nashville, TN sit-ins. He and his wife survive. (History Makers post about Looby)

April 19, 1960: terrorists bomb the home of Z. Alexander Looby, a Nashville civil rights lawyer who defended students arrested in Nashville, TN sit-ins. He and his wife survive. (History Makers post about Looby)

Greensboro arrests

April 21, 1960: police arrested forty-five students (including Ezell Blair, Jr., Joseph McNeil, David Richmond and 13 Bennett College students) for trespassing as they sat at the Kress store lunch counter. All were released without bail.

In June 1960: when N.C. A&T and Bennett College students left the Greensboro for the summer, Dudley High School students took up the charge. William Thomas led the students as the protests expanded to Meyers and Walgreen.

Greensboro 4 Desegregate Lunch Counters

Woolworth relents

July 21, 1960: F.W. Woolworth manager Clarence Harris met with Chairman Zane and the Advisory Committee in his store. He informed them that F.W. Woolworth’s would soon serve all properly dressed and well-behaved people. Kress manager H.E. Hogate was present.

July 25, 1960: F.W. Woolworth employees Charles Bess, Mattie Long, Susie Morrison and Jamie Robinson were the first African-Americans to eat at the lunch counter. The headline of The Greensboro Record read “Lunch Counters Integrated Here”. The Kress counter opened to all on the same day.

July 26, 1960: F.W. Woolworth desegregated.

Desegregation expands

October 17, 1960: in response to the sit-ins that had began on February 1, several chain stores announced on this day that they would desegregate their lunch counters in North Carolina, Virginia, Tennessee and seven other southern states. This decision was arguably the greatest single victory for the sit-in movement, but many restaurants continued to segregate.

Sit-ins continue

October 19, 1960: King was arrested along with students, eventually numbering 280, after conducting mass sit-ins at Rich’s Department Store and other Atlanta stores. The others were freed, but the judge sentenced King to four months in prison. Legal efforts secured his release after eight days. A boycott of the store followed, and by the fall of 1961, Rich’s began to desegregate.

By August 1961, more than 70,000 people had participated in sit-ins, which resulted in more than 3,000 arrests. Sit-ins at “whites only” lunch counters inspired subsequent kneel-ins at segregated churches, sleep-ins at segregated motel lobbies, swim-ins at segregated pools, wade-ins at segregated beaches, read-ins at segregated libraries, play-ins at segregated parks and watch-ins at segregated movies.