Scottsboro Nine Travesty

The phrase “Scottsboro Boys” evokes both our history of demeaning racial stereotyping as well as another horribly unfair example of American justice denied to African-Americans.

Some might say that the wheel of Fortune simply frowned upon these nine young men one day in 1931, just as it was doing to Americans of “another” color. They were just young men in the wrong place at the wrong time, but the odds of miscarried justice for blacks have always been higher.

Their story is a long one that became a cause célèbre for the American Communist party, progressives, the NAACP and a chance for newspapers to increase circulation.

Scottsboro Nine Travesty

March 25, 1931

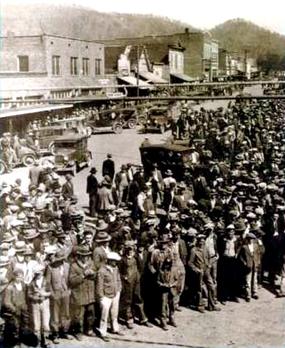

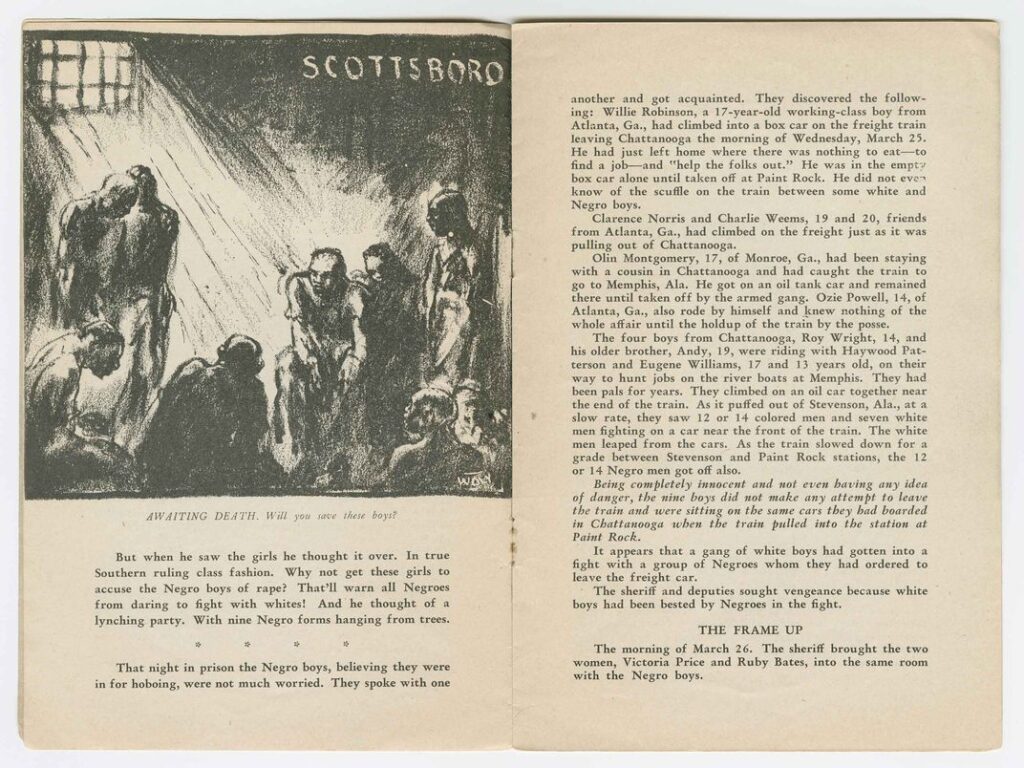

On March 25, 1931 the nine black youths were “hoboing” on a Southern Railroad freight train. Several white males and two white women were also on the train. A fight began between the white and black groups and the whites were kicked off the train. The whites complained to authorities. A posse stopped the train in Paint Rock, Alabama. They arrested the group on charges of assault. The authorities added rape charges against all nine after Victoria Price and Ruby Bates, the two girls on the train, made accusations.

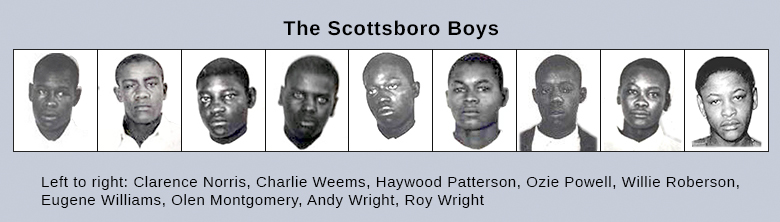

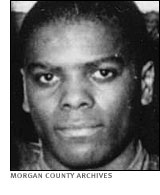

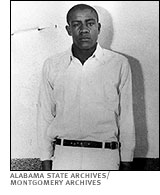

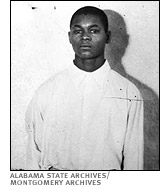

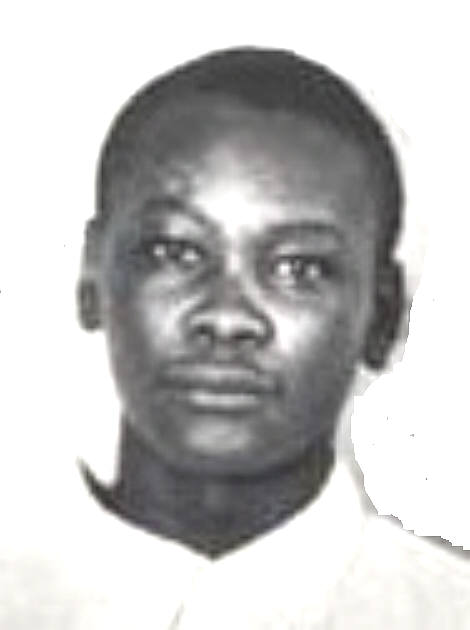

The youths arrested were Olen Montgomery (age 17), Clarence Norris (age 19), Haywood Patterson (age 18), Ozie Powell (age 16), Willie Roberson (age 16), Charlie Weems (age 16), Eugene Williams (age 13), and brothers Andy (age 19) and Roy Wright (age 12).

The posse brought the nine to Scottsboro, Alabama. On March 26, a crowd gathered around the Scottsboro jail to lynch the nine youths. Sheriff Matt Wann telephoned Governor Benjamin M. Miller who then called in the National Guard to protect the jail before taking the defendants to Gadsden, Alabama for indictment and to await trial.

On March 30, 1931 a grand jury indicted all nine for rape. Although rape was potentially a capital offense, the defendants were not allowed to consult an attorney because they were being kept “for their safety” in death row cells and that area of the prison did not permit lawyers to speak unattended.

Scottsboro Nine Travesty

Swift Injustice

Over April 6 – 7, 1931 before Judge A. E. Hawkins, Clarence Norris and Charlie Weems were tried, convicted, and sentenced to death. A threatening crowd gathered outside the courthouse. Victoria Price testified that six of the black youths raped her, and six raped Ruby Bates. Ruby Bates was not present.

The only legal help the defendants’ parents could afford was a real estate lawyer with no criminal defense experience. He had met with all nine for less than 30 minutes before the trials.

Over April 7 – 8, 1931 Haywood Patterson was tried, convicted, and sentenced to death.

Over April 8 – 9, 1931 Olen Montgomery, Ozie Powell, Willie Roberson, Eugene Williams, and Andy Wright were tried, convicted, and sentenced to death.

On April 9, 1931 the case against Roy Wright, aged 13, ended in a hung jury when 11 jurors seek a death sentence, and one voted for life imprisonment.

That same day, Judge Hawkins sentenced the eight convicted defendants to death by electric chair. He set the executions for July 10, 1931, the earliest date Alabama law allowed.

Scottsboro Nine Travesty

Stayed executions

June 22, 1931 Alabama Supreme Court stayed executions pending appeal.

The New York Times had reported the arrest and protection sought by Sheriff Matt Wann. The American Communist party was always on the look out for such discrimination. With that exposure, the NAACP and the Communist Party’s legal arm, the International Labor Defense, offered help. The young men’s parents selected the ILD. George W. Chamlee was the ILD lawyer.

Scottsboro Boys Travesty

1932

Case unravels but bias does not

January 5, 1932,: Ruby Bates, one of the two girls who accused the the nine of rape, denied that she was raped. In a letter Bates wrote her then boyfriend, Earl Streetman, she wrote: “those Negroes did not touch me….i hope you will believe me the law dont….i wish those Negroes are not Burnt on account of me.”

March 24, 1932 the Alabama Supreme Court, by a vote of 6-1, affirmed seven the convictions. It reversed the conviction of Eugene Williams on the grounds that he was a juvenile under state law in 1931.

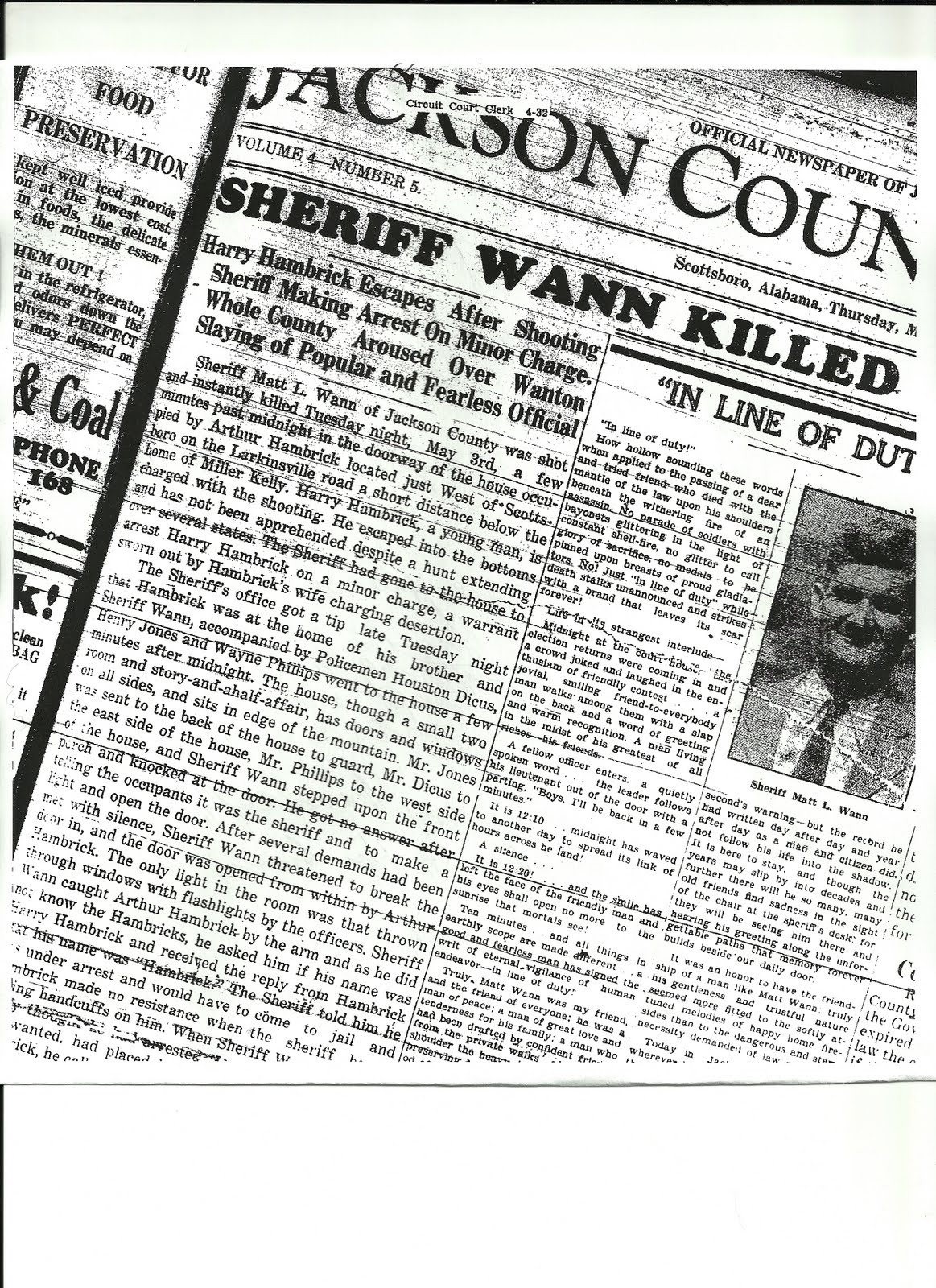

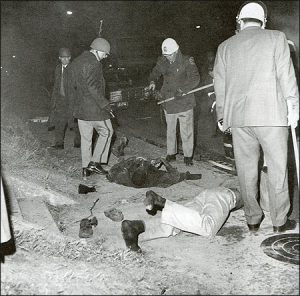

May 3, 1932 Harry Hambrick killed Sheriff Matt Wann when Wann attempted to serve a warrant for his arrest for the failure to support his wife.

Wann had mistakenly arrested Hambrick’s brother and Harry Hambrick shot and killed Wann. Hambrick was never caught nor tried in abstencia. Several deputies were with Wann assisting with the arrest.

On May 27, 1932 the U.S. Supreme Court announced it would hear the Scottsboro cases.

Not quite Free Speech

October 2, 1932, American Legion members helped Los Angeles police break up a rally of 1,000 people at the Long Beach Free Speech Zone, who were supporting the nine defendants. Police arrested two people, which was one of 11 political meetings reportedly broken up by LA police in 1932, often with assistance of the American Legion.

Powell v. Alabama

On November 7, 1932 in Powell v. Alabama, the Supreme Court reversed the convictions by a vote of 7 – 2. The Court ruled that Alabama had denied the right to counsel to the defendants, which violated their right to due process under the Fourteenth Amendment. The Court remanded the cases to the lower court.

Scottsboro Nine Travesty

1933

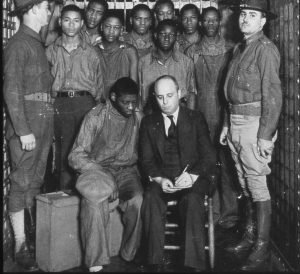

January, 1933 the International Labor Defense retained Samuel S. Leibowitz, a New York lawyer, to defend the nine.

March 10, 1933: Roy Wright told New York Times reporter Raymond Daniell, “They whipped me and it seemed like they was going to kill me. All the time they kept saying, “now will you tell?” and finally it seemed like I couldn’t stand no more and I said yes. Then I went back into the courtroom and they put me up on the chair in front of the judge and began asking a lot of questions, and I said I had seen Charlie Weems and Clarence Norris with the white girls.”

Scottsboro Nine Travesty

New trials

March 27, 1933 Haywood Patterson’s second trial began before another all-white jury. Ruby Bates testified that no one had raped either Victoria Price or her on the Southern Railway.

“…Jew money”

April 7, 1933, summing up for the State at the close of the first of the new-Scottsboro trials, Wade Wright, circuit solicitor of Morgan County, Alabama, made a frank appeal to local pride, sectionalism, race hatred, and bigotry.

“Show them,” he said pointing at the counsel table at which were seated Sameul S Leibowitz of NY, chief defense counsel and Joseph Brodsky, counsel for the International Labor Defense, a Communist affiliate, — “show them that Alabama justice cannot be bought and sold with Jew money from New York”

April 9, 1933 a jury found Haywood Patterson guilty and sentenced him to death in the electric chair.

April 14, 1933, approximately 10,000 people attended a International Labor Defense meeting in NYC’s Union Square. The ILD asked for unity among white and blacks and to fight for the release of the nine defendants.

April 19, 1933,Judge Horton postponed the trials of the other Scottsboro defendants because of dangerously high local tensions. The judge feared that local tensions were too strained to result in a “just and impartial verdict.”

May 5, 1933 Ruby Bates, and appeared as a defense witness. She also declared at a public appearance that the “the Scottsboro boys are innocent.”

May 8, 1933: in one of many protests across the country, thousands march in Washington D.C. to protest the Alabama trials.

Scottsboro Nine Travesty

New Judge

October 20, 1933, Alabama Judge William Callahan took over the remaining cases from Judge Horton’s jurisdiction.

From PBS: “After Judge James Horton was asked to step down from the Patterson case, all the Scottsboro cases were transferred to Judge Callahan’s court. Unlike Horton, Callahan forbade cameras in his courtroom (“There ain’t going to be no more picture snappin’ round here,” he declared) and made clear that the press was much less welcome. Callahan tried to keep the case as straightforward as possible, limiting many of defense attorney Samuel Leibowitz’s objections and sustaining most of the prosecution’s objections of Leibowitz — and even chiming in with a few objections of his own.” PBS site

November 20, 1933: the seven oldest of the nine were tried in front of the new judge and jury. Haywood Patterson and Clarence Norris were sentenced to death.

Scottsboro Nine Travesty

1934

May 3, 1934: after a May Day rally to support them, Olen Montgomery wrote to his mother: “That thing they had here on May Day what good did it do. Not any at all. I’m still locked up in the cell. Instead of the I.L.D. trying to make it better for me here in jail they are making it harder for me by trying to demand the people to do things. Listen, send me some money. Send me three dollars like I told you in my first letter.”

June 12, 1934: Judge Horton, who had faced no opposition in his previous race, lost in his bid for re-election.

June 28, 1934: Samuel Leibowitz had filed for new trials. Ruling unanimously, the Alabama Supreme Court denied his request.

Scottsboro Nine Travesty

1935

January 1935: The US Supreme Court agreed to review the most recent Scottsboro convictions.

February 15, 1935: Samuel Leibowitz argued before the US Supreme Court that Alabama courts had excluded blacks from the Scottsboro jury pool because of their race. Leibowitz claimed that the black names currently on the jury rolls had been forged in after the fact.

April 1, 1935: in Norris v. Alabama, the US Supreme Court ruled that the exclusion of black citizens on jury rolls deprived the Scottsboro defendants of their rights to equal protection under the law as guaranteed by the Fourteenth Amendment. The Court overturned the convictions of Haywood Patterson and Clarence Norris and remanded the cases to a lower court.

November 13, 1935: Creed Conyer became the first post-Reconstruction black person to sit on an Alabama grand jury in the remanded case.

December 1935: The Scottsboro Defense Committee formed with representatives of the NAACP, the International Labor Defense, the American Civil Liberties Union, the League for Industrial Democracy, and the Methodist Federation for Social Service. The organization’s main objective was to provide a united defense for the Scottsboro defendants.

Scottsboro Nine Travesty

1936

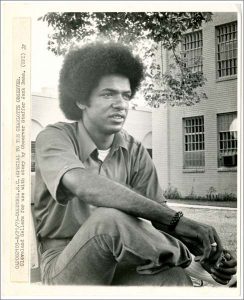

Haywood Patterson

January 23, 1936: a jury convicted Haywood Patterson for a fourth time of rape. The sentence was lower from death to 75 years in prison. This was the first time in Alabama history a black man was sentenced to anything other than death for the rape of a white woman.

Following his sentence, Powell said, “I’d rather die than spend another day in jail for something I didn’t do.”

Ozie Powell

January 24, 1936: a day later, Powell was shot in the skull after he pulled a knife on a deputy sheriff. Powell survived the injury but suffered lasting damage. Rape charges against him were dropped. He pleaded guilty in the assault on the officer and was sentenced to 20 years in prison.

in December, 1936 after the Supreme Court again reversed the convictions of the Scottsboro defendants in 1936, Alabama Attorney General Thomas E Knight, Jr met secretly with their attorney Samuel S Leibowitz in New York to discuss a possible compromise. Knight told Leibowitz he was “sick of the cases,” and that they were causing Alabama considerable political and economic harm.

According to Leibowitz, Knight by that time had come to believe that Price was lying and no rape had ever occurred. Nonetheless, he thought jail time appropriate because at least some of the defendants were guilty of assault for having thrown the white boys off the train. After several meetings between the two, they reached a compromise that would result in the release of four of the defendants and a reduction of sought charges for the others.

Scottsboro Nine Travesty

1937

May 17, 1937 Alabama Attorney General Thomas Knight died. His proposed compromise was never carried out in full by the state because the new acting attorney general feared “looking soft” on rape.

June 14, 1937: Haywood Patterson’s conviction upheld by the Alabama Supreme Court.

July 15 1937: Clarence Norris convicted of rape and sentenced to death

July 22, 1937: Andy Wright convicted and sentenced to 99 years.

Scottsboro Nine Travesty

July 24, 1937

- Charlie Weems convicted and sentenced to 105 years

- Ozie Powell pled guilty to assaulting Sheriff Edgar Blalock and sentenced to 20 years.

- All charges against Roy Wright and Eugene Williams dropped, on account of their young age at the time of the crime, and the number of years already served.

- the charges against Olen Montgomery and Willie Roberson dropped on the grounds that the state no longer believes the men to be guilty.

- an attorney picked up the newly freed men and drove them to New York City, where they appeared on stage in Harlem as performers and as curiosities. Montgomery and Leroy Wright participated in a national tour to raise money for the five men still imprisoned.

October 26, 1937: the US Supreme Court declined to review the Haywood Patterson and Clarence Norris convictions.

Scottsboro Nine Travesty

1938

Warped Arc of Justice

in June 1938 the Alabama Supreme Court upheld the death sentence for Clarence Norris.

July 5, 1938 Alabama Governor David Bibb Graves reduced Clarence Norris’s death sentence to life in prison.

In August 1938 the Alabama Pardon Board declined to pardon Haywood Patterson and Ozie Powell.

in October 1938 the Alabama Pardon Board denied the pardon applications of Clarence Norris, Charlie Weems, and Roy Wright.

In November 1938: Alabama Governor Graves denied all pardon applications.

Scottsboro Nine Travesty

1940s

in September 1943: Charlie Weems paroled.

in January 1944: Clarence Norris and Andy Wright paroled.

in October 1944: Clarence Norris. After fleeing north, Norris was convinced to return to Alabama, in large measure to improve the lot of the two remaining Scottsboro defendants. Although promised leniency, Norris was returned to prison. Two years later, in 1946, Norris was paroled again.

in June 1946: Ozie Powell paroled.

in October 1946: Andy Wright. The work the parole board had found seemed no better than prison to Andy, and he fled north. Allan Knight Chalmers, the chairman of the Scottsboro Defense Committee persuaded him to return south, in part so that Patterson and Powell’s parole hearings might have more favorable results. When Wright returned, he was imprisoned despite promises of leniency.

In July 1948: Haywood Patterson escaped from prison. Patterson sought the help of a journalist, Earl Conrad, and together they wrote The Scottsboro Boy, an account of Patterson’s life.

Scottsboro Nine Travesty

1950s

In May 1950, Andy Wright was paroled again, and Chalmers found a job for him in an Albany hospital. When asked about Victoria Price upon his release, Andy said: “I’m not mad because the girl lied about me. If she’s still living, I feel sorry for her because I don’t guess she sleeps much at night.” He was the last Scottsboro defendant to leave jail.

in December 1950: Haywood Patterson involved in a Michigan barroom fight resulting in the death of another man. Haywood charged with murder. FBI arrested Haywood Patterson, but Michigan’s governor refuses extradition to Alabama.

September 24, 1951: Haywood Patterson convicted of manslaughter and sentenced to 6 to 15 years. He died of cancer in jail on August 24, 1952. He was 39.

August 16, 1959: living in NYC Roy Wright had had a career in the US Army and the Merchant Marines. After his wife admitted to infidelities Wright shot and killed his wife and then committed suicide.

Scottsboro Nine Travesty

1970s

In 1970, Clarence Norris surfaced in New York City with a wife and two children.

In 1976 Victoria Price resurfaced. Now known as Katherine Queen Victory Street, she was suing NBC for slander and invasion of privacy for the broadcast of Judge Horton and the Scottsboro Boys, a television movie. She had married twice more since World War II and was living in Tennessee. She returned to the witness stand for her suit and told her story for the twelfth time in a court of law.

October 26, 1976: Alabama Governor George Wallace pardoned Clarence Norris.

October 27, 1976: Ruby Bates died at age sixty-three.

In July 1977, the Courts dismissed Victoria Price’s defamation and invasion of privacy suit against NBC.

In 1979 Clarence Norris, in ”The Last of the Scottsboro Boys,” a 1979 autobiography written with Sybil D. Washington, contended that the black youths were scapegoats, caught at the wrong place at the wrong time with two white women who were afraid they would be accused of fraternizing with blacks.

Scottsboro Nine Travesty

1980s

In 1982 Victoria Price died without ever having apologized for her role in the injustice her testimony brought upon the innocent defendants.

January 23, 1989: Clarence Norris, assumed to be the last surviving Scottsboro defendant, died of Alzheimer’s disease at age 76. (see “Postscript” below)

Scottsboro Nine Travesty

21st Century

January 19, 2001: Cowboy Pictures released Scottsboro: An American Tragedy. It was a documentary film directed by Daniel Anker and Barak Goodman and written by Barak Goodman.

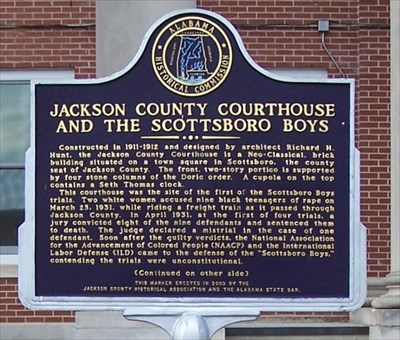

In January 2004: the town of Scottsboro, Alabama dedicated an historical marker in commemoration of the case at the Jackson County Court House.

Scottsboro Boys Museum

From it’s site: The Scottsboro Multicultural Foundation established the Scottsboro Boys Museum and Cultural Center. The Museum’s opening was the culmination of a 17-year effort led by Scottsboro native Shelia Washington, chairperson of the Museum and executive committee member of the Foundation, to bring honor and dignity to the lives and cases of nine black teenagers” Scottsboro Boys Museum

March 10, 2010, The Scottsboro Boys, a musical with a book by David Thompson, music by John Kander and lyrics by Fred Ebb. The musical was one of the last collaborations between Kander and Ebb prior to the latter’s death. The musical had the framework of a minstrel show, altered to “create a musical social critique” with a company that, except for one, consists “entirely of African-American performers”.

The musical debuted Off-Broadway and then moved to Broadway in 2010 for a run of only two months. It received twelve Tony Award nominations,

April 4, 2013: Alabama Lawmakers voted to issue posthumous pardons to the nine black teenagers who were wrongly convicted of raping two white women more than 80 years earlier based on false accusations. Gov. Robert Bentley had to sign the bill setting up a procedure to pardon the group, the so-called Scottsboro Boys, must be signed by to become law. He planned to study the legislation but has said he favored the pardons.

November 21, 2013: the State of Alabama posthumously pardoned Haywood Patterson, Charles Weems and Andy Wright, thus absolving the last of the so-called Scottsboro Boys. During a hearing in Montgomery, the Alabama Board of Pardons and Paroles voted unanimously to issue pardons to the three men.

Scottsboro Nine Travesty

Postscript…

Above it stated that when Clarence Norris died in 1989, he was the last of the nine defendants to die. The time of death for some of the defendants is unknown.

- Olen Montgomery was born in 1914. The last information about him is that he spent his days in New York or Atlanta occasionally receiving financial help from the NAACP.

- Ozie Powell, born in 1916, lived and apparently died in Atlanta, Georgia.

- Willie Roberson, born in 1915, had asthma that had been greatly aggravated by his time in jail and he eventually died of an asthma attack.

- Charles Weems, born in 1911, married and settled down into obscurity. While in prison, guards tear-gassed Weems in his cell for reading International Labor Defense literature. His eyes never fully recovered.

- Eugene Williams, born in 1918, had a a brief entertainment career, before moving to St. Louis where he had relatives who helped him adjust to a relatively stable life.

- Andy Wright, born in 1912, had settled in Albany, NY, but eventually settled in Connecticut.