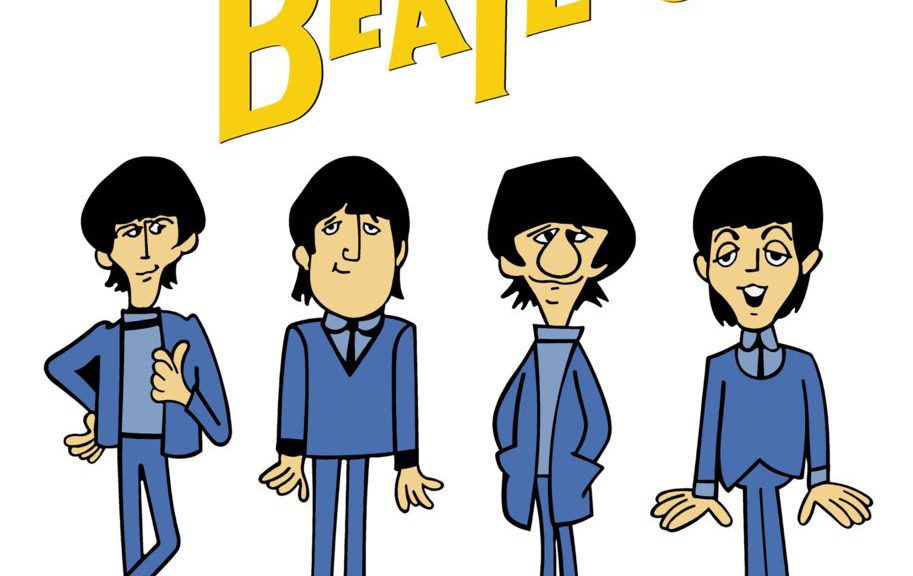

1965 Beatles Cartoon Series

September 25, 1965

Beatles ’65

By September 1965 the Beatles were king of the media hill. They already had had four #1 singles for a total of 9 weeks (“I Feel Fine,” “Eight Days a Week,” “Ticket to Ride,” and “Help.”) and three #1 albums for a total of 31 weeks (Beatles 65, Beatles VI, and Help)!

Rubber Soul, the album that changed the direction of pop music like no other, was on the December horizon.

Odd as it may seem, those incredibly great numbers and three Grammy nominations resulted in no Grammy awards at the 1966 ceremony.

1965 Beatles Cartoon Series

The Beatles were a HOT commodity!

Do a search for Beatle memorabilia on E-Bay to get a taste of the enormous number of novelty items still available. The ABC TV network jumped onto the Beatle band wagon because ABC recognized a golden egg when they saw one. Each Beatle was a golden goose and they were laying clutches of golden eggs.

1965 Beatles Cartoon Series

ABC

On September 25, 1965 ABC broadcast the first Beatles cartoon. No need to be clever, the network simply called the show The Beatles.

The Saturday 10:30 AM time slot showed what demographic ABC sought: young adolescents.

Each episode’s story line highlighted a Beatle song or two. For example, the first episode was called A Hard Day’s Night/I Want to Hold Your Hand. The Beatle characters were rehearsing at Transylvania Hilton, but fans keep getting in the way.

Ringo said he knew a place that was big and empty. Paul responded, “Sounds fine, but how do we all fit inside your head?”

Ba-dump-ba! And away we go.

1965 Beatles Cartoon Series

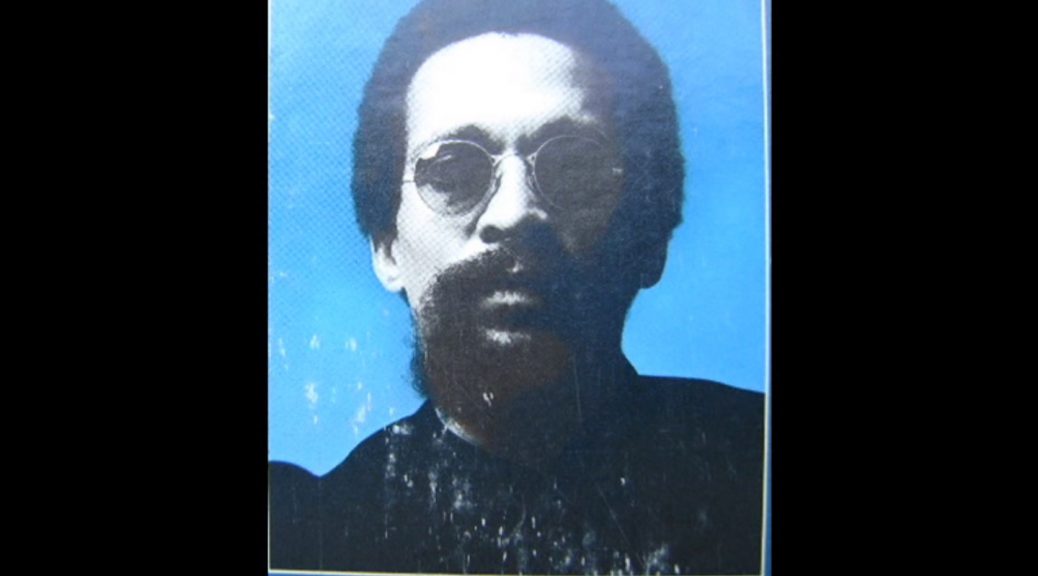

Paul Frees

The Beatles themselves were not part of the production. Al Brodax and Sylban Buck created the show and King Features Syndicate produced it. American actor Paul Frees did the John and George voices. You may not recognize his name, but chances are you do recognize one of his many voices!

1965 Beatles Cartoon Series

End

British actor Lance Percival did the Paul and Ringo voices.

The Beatles were not enthusiastic about the production at first, but later came to like the idea and the various episodes.

The series ended on September 7, 1969 after a total of 39 episodes. ABC moved the 1967 season to Saturdays at noon. The fourth “season” was re-runs shown Sunday mornings at 9:30.

MTV rebroadcast the series in 1986 and 1987 and the Disney Channel in 1989.

We can easily find the episodes now on YouTube

1965 Beatles Cartoon Series

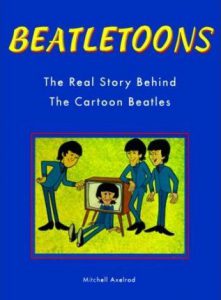

BeatleToons

In 1999, Mitchell Axelrod wrote BeatleToons, The Real Story Behind The Cartoon Beatles.

In 2015, Rolling Stone magazine had an article marking the 50th anniversary of the show.

1965 Beatles Cartoon Series

Yellow Submarine

The Beatles weren’t too crazy about the idea of the Yellow Submarine movie either until they saw some outtakes from it. Al Brodax was a producer and co-writer of that film and the film’s director, George Dunning, had worked on the cartoon series. Voice actors performed the parts including Lance Percival (who did not do a Beatle voice).

To fulfill their contractual obligation with United Artists, they appeared “live” at the end of the film and sang “All Together Now.”