Walter Cronkite Vietnam

February 27, 1968

Walter Cronkite Vietnam

The News

In 1968 you got your news from newspapers, radio, or TV. Newspapers typically published a morning edition, though there were certainly afternoon papers that the grammar school paperboy delivered while listening to his transistor radio.

At 7 PM (ET), that paperboy might have sat down with his father (Mom was putting younger siblings to bed) and watched the half-hour evening news. There were three networks: ABC, NBC, and CBS and until 1963 the shows were just 15 minutes long.

Walter Cronkite Vietnam

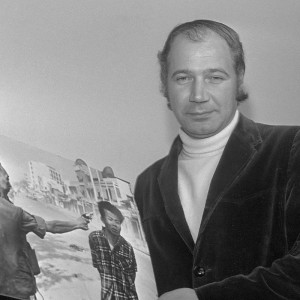

Walter Cronkite

The news anchors were Chet Huntley and David Brinkley on NBC, Frank Reynolds on ABC, and Walter Cronkite on CBS. They ruled the news airwaves, particularly Walter Cronkite, who was sometimes referred to as “the most trusted man in America.” I learned the word avuncular when someone used it describing him.

Every news organization has biases. It selects what to report and what not to report, but the aim is to be objective. Reports tried to stick with observable facts. Editorializing during the evening news was unusual.

Reporting from the field was different, too. Unlike today when reporters are “embedded” with a military group and go only where that group go, reporters then could go where they could go. In other words, if a reporter could find a way to get to the front or wherever, that reporter could go there.

Walter Cronkite Vietnam

Tet Offensive

On January 30, 1968, the Viet Cong and North Vietnam Army troops launched the Tet Offensive attacking a hundred cities and towns throughout South Vietnam. The surprise offensive was closely observed by American TV news crews in Vietnam which filmed the U.S. embassy in Saigon being attacked by 17 Viet Cong commandos, along with bloody scenes from battle areas showing American soldiers under fire, dead and wounded. The graphic color film footage was then quickly relayed back to the states for broadcast on nightly news programs.

While the American and South Vietnamese troops repulsed the Tet Offensive, the near success of the campaign forced many back home to question the idea that we had been in control, that we were winning, that the war would end soon. Questioned particularly in light of Gen. William Westmoreland, commander of U.S. Military Assistance Command Vietnam, telling U.S. news reporters the previous November: “I am absolutely certain that whereas in 1965 the enemy was winning, today he is certainly losing.”

Walter Cronkite Vietnam

February 27, 1968

On February 27, 1968, Walter Cronkite delivered the news as always: objectively and calmly, but at the end of his report he did something unusual.

Prepared. Not off script. Cronkite said…

Tonight, back in more familiar surroundings in New York, we’d like to sum up our findings in Vietnam, an analysis that must be speculative, personal, subjective. Who won and who lost in the great Tet Offensive against the cities? I’m not sure. The Vietcong did not win by a knockout but neither did we.

We’ve been too often disappointed by the optimism of the American leaders…

Both in Vietnam and Washington to have faith any longer in the silver linings they find in the darkest clouds. For it seems now more certain than ever, that the bloody experience of Vietnam is to end in a stalemate. To say that we are closer to victory today is to believe in the face of the evidence, the optimists who have been wrong in the past.

To say that we are mired in stalemate seems the only realistic, if unsatisfactory conclusion. On the off chance that military and political analysts are right, in the next few months we must test the enemy’s intentions, in case this is indeed his last big gasp before negotiations.

But it is increasingly clear to this reporter that the only rational way out then will be to negotiate, not as victors, but as an honorable people who lived up to their pledge to defend democracy, and did the best they could.

This is Walter Cronkite. Good night.

Here is a piece of that report:

The common story after Cronkite’s report is that President Lyndon Johnson turned to his press secretary, George Christian, and said, “If I’ve lost Cronkite, I’ve lost the country.”

It can be argued that Cronkite’s statement didn’t actually have the impact that history credits it, but it can’t be argued that at time of relatively limited news media when a generally well-respected man whom people watched five nights a week and depended upon for their news went against something, opinion scales were tipped toward getting out of Vietnam.

- Reference >>> NPR report

- Reference >>> PBS essay on Cronkite

- Reference >>> full text of editorial