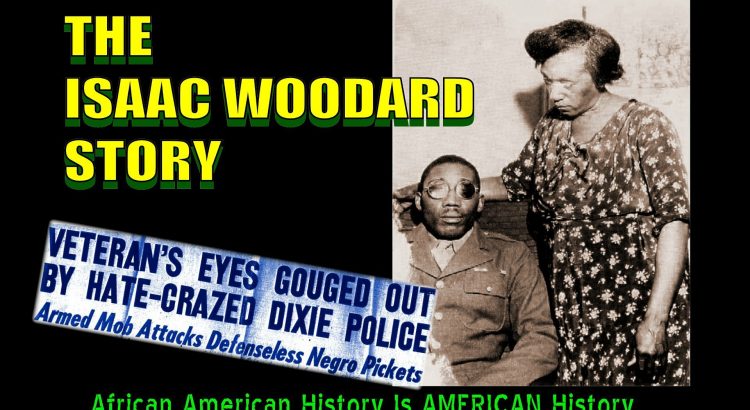

Shull blinds Isaac Woodard

Remembering Isaac Woodard

March 18, 1919 – September 23, 1992

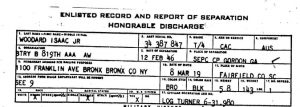

Honorable Discharge

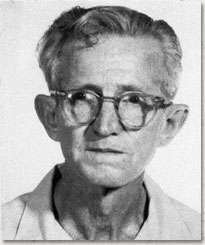

Isaac Woodard grew up in North Carolina and on October 14, 1942 he enlisted in the U.S. Army becoming one of the one million African-Americans who served in the U.S. military during World War II.

He served in the Pacific Theater in a labor battalion as a longshoreman and was promoted to sergeant. He earned a battle star for his by unloading ships under enemy fire in New Guinea.

On February 12, 1946 he received an honorable discharge.

Shull blinds Isaac Woodard

Rest Stop

That same day the 26-year-old Woodard Jr, still in uniform, was on a Greyhound Lines bus traveling from Camp Gordon in Augusta, Georgia. He was en route to Winnsboro, South Carolina to pick up his wife and then go to New York City with her to visit his parents.

A a stop in North Carolina he asked the bus driver if there was time to use the restroom. The driver cursed and said “No.” Woodard cursed back. The driver said to go and hurry.

Woodard did.

Shull blinds Isaac Woodard

Beating

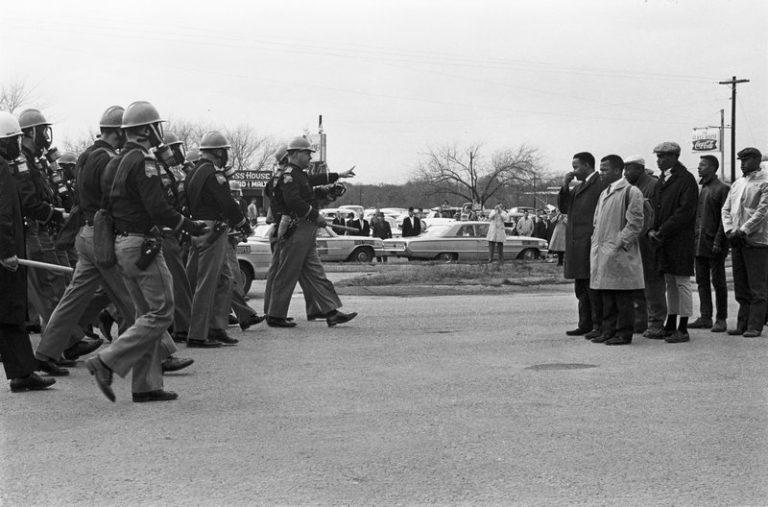

Later, the driver stopped the bus in Batesburg (now Batesburg-Leesville, South Carolina), near Aiken. He contacted the police and told them that a passenger was drunk and causing a disturbance on the bus.

The police arrived and the driver told Woodard to leave the bus. He did. The driver told the police that Woodard was the one who’d been drunk and disorderly. Woodard tried to explain that he was neither, but the police struck Woodard with a billy club.

A struggle ensued, but other police stepped in, threatened to shoot Woodard, and he gave up.

The police took Woodard to the town jail, knocking him out on the way, and arrested him for disorderly conduct, accusing him of drinking beer in the back of the bus with other soldiers. The repeated beatings had blinded Woodard.

Shull blinds Isaac Woodard

Jailed, guilty, fined, hospitalized

The following morning, the police sent Woodard before the local judge, who found him guilty and fined him fifty dollars. The soldier requested medical assistance, but it took two more days for a doctor to be sent to him. Not knowing where he was and suffering from amnesia, Woodard ended up in a hospital in Aiken, South Carolina, receiving substandard medical care.

Three weeks after he was reported missing by his relatives, Woodard was discovered in the hospital. He was immediately rushed to a US Army hospital in Spartanburg, South Carolina. Though his memory had begun to recover by that time, doctors found both eyes were damaged beyond repair.

Shull blinds Isaac Woodard

NAACP

July 25, 1946: the NY Times reported that after a July 24 meeting at the New York headquarters of the NAACP, “Charles Bolte, national chairman of the American Veterans Committee, Charles Klair, director of the veterans’ bureau of the CIO, Aurhtur Pearl of the Duncan Parish Post, Marican Legion, Barnard Harker of the American Jewish Congress, and representatives of the United Negro and Allied Veterans and the Hawaiian Association for Civic Unity, members of several veterans’ organizations and civic groups voted yesterday to form a committee to seek compensation for Woodard.

Waler White, the NAACP executive secretary, urged support of petitions to President Truman and the Veterans Administration to have Woodard’s case adjudicated as having happened in the line of duty as Woodard had been discharged less than 24 hours when the blinding occurred.

Shull blinds Isaac Woodard

Cause célèbre

Orson Wells, the well-known actor, director, and radio personality took up Woodard’s story.

On July 28, 1946, on his popular ABC radio show, Wells’s read of the deposition and followed with his own comments. Well’s next four broadcasts continued to include comments regarding Woodard’s story.

The citizens of Aiken became incensed over Welles’s broadcasts and requested an apology.

In later broadcasts, Wells would refer to Aiken’s request, but issued no apology.

On August 6, 1946, the Aiken’s Lions Club issued a statement that read in part, “We as citizens and business men of Aiken have implicit confidence in these officials and, having been advised of the circumstances of this case, are convinced that this incident did not occur in Aiken, SC.” (NYT abstract)

Shull blinds Isaac Woodard

Blinded Veterans Association

August 8, 1946: more than 400 members of the Blinded Veterans Association welcomed Woodard as a member at the Association headquarters in NYC.

A NYT article about the event reported that the NAACP had filed an application to American Red Cross on Woodard’s behalf for the injuries he received.

Shull blinds Isaac Woodard

Aiken exonerated

August 13, 1946: media had reported that the Woodard beating and blinding had occurred in the town of Aiken, South Carolina, On this date, Leo M Cadison, Deputy Director of the Division of Public Information in Washington, DC sent Aiken telegram that exonerated the city from blame. (NYT abstract)

Shull blinds Isaac Woodard

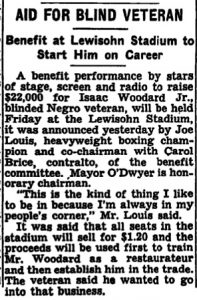

Benefit Concert

August 18, 1946: The Amsterdam News Welfare Fund and the Isaac Woodard Benefit Committee held a concert for Woodward in Lewisohn Stadium in New York City. The benefit included such entertainers as Orson Welles, Woody Guthrie, Cab Calloway, Billie Holiday and Milton Berle. 20,000 attended.

NYC Mayor o”Dwyer spoke saying, “first and foremost there must be equal protection by those entrusted with law enforcement, and here there can be no equivocation and no discrimination in treatment. Commissioner Wallander of the Police Department has recently issued a statement of policy to the police fore, again emphasizing to them this well understood policy of my administration. That directive must be observed as long as I am Mayor of New York, not only in the police, but all other departments.” (NYT abstract)

Woody Guthrie later wrote the song “The Blinding of Isaac Woodard” “so’s you wouldn’t be forgetting what happened to this famous Negro soldier less than three hours after he got his Honorable Discharge down in Atlanta….” (lyrics from the fortune city site)

Shull blinds Isaac Woodard

President Truman intervenes

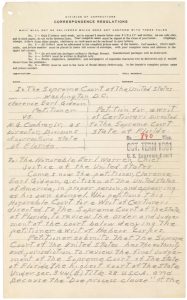

September 19, 1946, NAACP Executive Secretary Walter Francis White met with President Harry S. Truman in the Oval Office to discuss the Woodard case. Gardner later wrote that when Truman “heard this story in the context of the state authorities of South Carolina doing nothing for seven months, he exploded.”

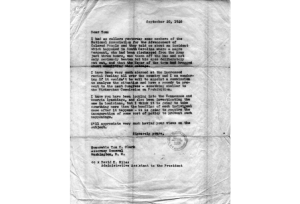

September 20, 1946: Truman wrote a letter to Attorney General Tom C. Clark demanding that action be taken to address South Carolina’s reluctance to try the case.

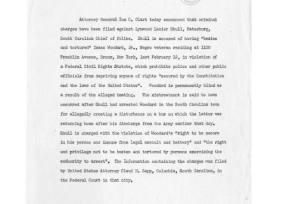

September 26, 1946: the US Department of Justice filed a criminal information in the Federal Court in Columbia, South Carolina alleging that Lynwood Shull had beaten and tortured Woodard in violation of the civil rights statute.

September 28, 1946: Shull posted a $2,000 bond for his appearance in the United States District Court on Nov. 4.

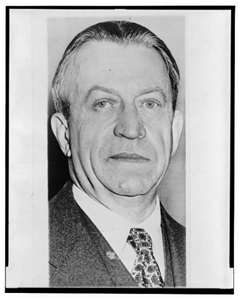

October 2, 1946: Chief of Police Lynwood Shull and several of his officers were indicted in U.S. District Court in Columbia, South Carolina. It was within federal jurisdiction because the beating had occurred at a bus stop on federal property and at the time Woodard was in uniform of the armed services. The case was presided over by Judge Julius Waties Waring.

Shull blinds Isaac Woodard

Travesty of a Trial

November 5, 1946: the trial ended. By all accounts, the trial was a travesty. The local U.S. Attorney charged with handling the case failed to interview anyone except the bus driver, a decision that Judge Waring, a civil rights proponent, believed was a gross dereliction of duty.

Waring later wrote of being disgusted at the way the case was handled at the local level, commenting, “I was shocked by the hypocrisy of my government…in submitting that disgraceful case….”

The defense did not perform better. When the defense attorney began to shout racial epithets at Woodard, Waring stopped him immediately. During the trial, the defense attorney stated to the all-white jury that “if you rule against Shull, then let this South Carolina secede again.” After Woodard gave his account of the events, Shull firmly denied it. He claimed that Woodard had threatened him with a gun, and that Shull had used his nightclub to defend himself. During this testimony, Shull admitted that he repeatedly struck Woodard in the eyes.

After thirty minutes of deliberation, the jury found Shull not guilty on all charges, despite his admission that he had blinded Woodard. The courtroom broke into applause upon hearing the verdict.

November 13, 1947: Woodward had sued the Atlantic Greyhound Corporation for $50,000. On this date, a jury decided against Woodard. (NYT abstract)

Shull blinds Isaac Woodard

Aftermath

Such miscarriages of justice by state governments influenced a move towards civil rights initiatives at the federal level. Truman subsequently established a national interracial commission, made a historic speech to the NAACP and the nation in June 1947 in which he described civil rights as a moral priority, submitted a civil rights bill to Congress in February 1948, and issued Executive Orders 9980 and 9981 on June 26, 1948, desegregating the armed forces and the federal government.

Isaac Woodard faded into obscurity while his story and the tragic stories of many other African-Americans continued be fuel for both those seeking equality and those seeking to continue the status quo.

Woodard lived in the New York City area for the rest of his life. He died at age 73 in the Veterans Administration Hospital in the Bronx on September 23, 1992.

He was buried with military honors at the Calverton National Cemetery (Section 15, Site 2180) in Calverton, New York.

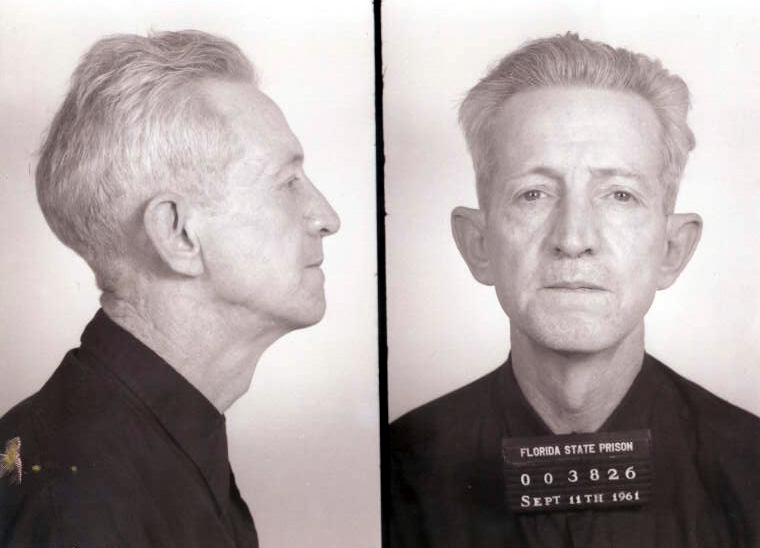

Shull blinds Isaac Woodard

Lynwood Shull died on 27 Dec 1997. He was 92.

Ridge Crest Memorial Park, Batesburg, Lexington County, South Carolina