MLK Jr Montgomery March

Preface

While most of us are familiar with the 1965 March to Montgomery, we may not be familiar with the spark that led to that famous, sometimes brutal, demonstration in support of voter registration.

Authorities had arrested and jailed the Rev James Orange in Perry County, Alabama on charges of disorderly conduct and contributing to the delinquency of minors. What had Orange specifically done? He had enlisted students to aid in voting rights drives.

Fearful that authorities might allow a lynching, on the night of February 18, around 500 people left Zion United Methodist Church in Marion and attempted a peaceful walk to the Perry County Jail about a half a block away where Orange was being held. The marchers planned to sing hymns and return to the church.

A line of Marion City police officers, sheriff’s deputies, and Alabama State Troopers met the marchers met at the Post Office. In the standoff, authorities had suddenly turned off the streetlights and the police began to beat the protestors. Among those beaten were two United Press International photographers, whose cameras were smashed, and NBC News correspondent Richard Valeriani, who was beaten so badly that he was hospitalized.

The marchers turned and scattered back towards the church.

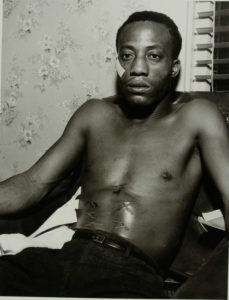

Pursued by Alabama State Troopers, twenty-six-year-old Jimmie Lee Jackson, his mother Viola Jackson, and his 82-year-old grandfather, Cager Lee, ran into a Mack’s Café behind the church. Police clubbed Cager Lee to the floor in the kitchen. The police continued to beat the cowering octogenarian Lee, and when his daughter Viola attempted to pull the police off. They beat her.

When Jimmie Lee attempted to protect his mother, one trooper threw him against a cigarette machine. A second trooper shot Jimmie Lee twice in the abdomen.

Jimmie Lee Jackson died at Good Samaritan Hospital in Selma on February 26. When civil rights organizer, James Bevel, heard of Jackson’s death he called for a march from Selma to Montgomery to talk to Governor George Wallace about the attack in which Jackson was shot. (see WW article on the long long road to justice for Jackson’s killer)

MLK Jr Montgomery March

The first attempt: Bloody Sunday

So, on Sunday 7 March 1965 about six hundred people left the Brown Chapel AME Church in Selma for a 54-mile march to the state capital of Montgomery.

So, on Sunday 7 March 1965 about six hundred people left the Brown Chapel AME Church in Selma for a 54-mile march to the state capital of Montgomery.

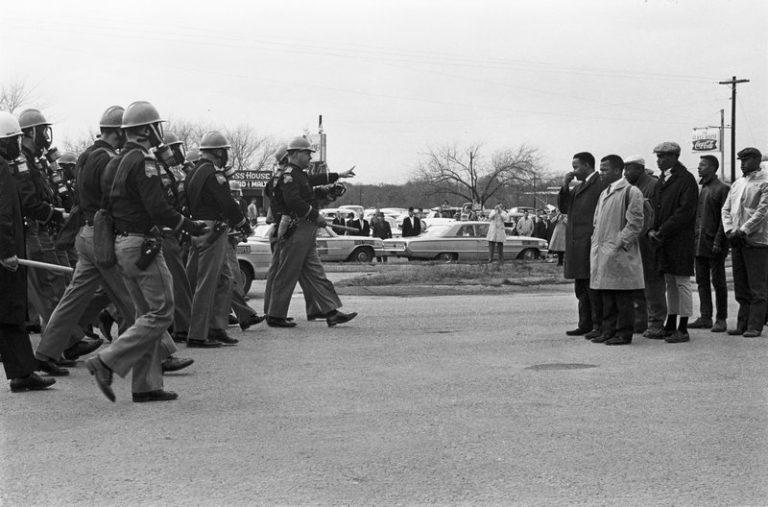

Southern Christian Leadership Conference’s Hosea Williams and Student Non-Violent Coordinating Committee’s John Lewis led them. A number of newsmen witnessed the long column of freedom singing marchers as they approached the Edmund Pettus Bridge, the gateway out of Selma.

Roughly 100 State Troopers, commanded by Major John Cloud, blocked the opposite end of the bridge. Hosea Williams tried to speak with Cloud twice, but the major said “There is no word to be had…you have two minutes to turn around and go back to your church.”

Within a minute, authorities attacked the marchers with tear gas, billy clubs, and charging horsemen. The incident was seen on national television. 16 marchers ended up in the hospital and another 50 received emergency treatment.

Media dubbed the incident “Bloody Sunday.”

MLK Jr Montgomery March

The second attempt: Turnaround Tuesday

On March 9, 1965, Martin Luther King, Jr led another march to the Edmund Pettus Bridge. About 2,000 people, more than half of them white and about a third members of the clergy, participated. King led the march to the bridge, then told the protesters to disperse.

That night White supremacists beat up white Unitarian Universalist minister James Reeb in Selma. Reeb died on March 11. (NYT abstract)

In April 1965, four men – Elmer Cook, William Stanley Hoggle, Namon O’Neal Hoggle, and R.B. Kelley – were indicted in Dallas County, Alabama for Reeb’s murder; three were acquitted by an all-white jury after a 95 minute deliberation that December. The fourth man fled to Mississippi and was not returned by the state authorities for trial.

In April 1965, four men – Elmer Cook, William Stanley Hoggle, Namon O’Neal Hoggle, and R.B. Kelley – were indicted in Dallas County, Alabama for Reeb’s murder; three were acquitted by an all-white jury after a 95 minute deliberation that December. The fourth man fled to Mississippi and was not returned by the state authorities for trial.

MLK Jr Montgomery March

Reorganizing/Re-strategizing

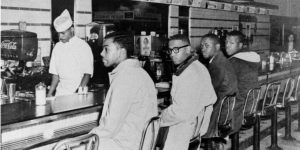

After the Turnaround Tuesday event and disagreeing with the the SCLC’s strategy in Selma, James Forman and much of the SNCC staff moved to Montgomery and began a series of demonstrations. The group also asked for students from across the country to join them. Tuskegee Institute students came to Montgomery in an attempt to deliver a petition to Wallace.

MLK Jr Montgomery March

Montgomery demonstrations

March 11, 1965: police arrested James Forman, executive director of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee, and others for blocking traffic on Capitol Hill after they had failed in an attempt to approach the State House. (NYT article)

On March 13, 1965 President Johnson met with Alabama’s Governor Wallace to decry the brutality surrounding the protests and asked him to mobilize the Alabama National Guard to protect demonstrators.

On March 13, 1965 President Johnson met with Alabama’s Governor Wallace to decry the brutality surrounding the protests and asked him to mobilize the Alabama National Guard to protect demonstrators.

March 14, 1965: SNCC staff members led 400 Alabama State University students, joined by a group of white students from across the country, on a march from the ASU campus to the Capitol. Although Montgomery police react peacefully to the march, as the students approach the Capitol, state troopers, the sheriff’s office, and a posse it had deputized attack the marchers.

That same day, fifteen thousand persons, including nuns, priests, ministers, rabbis, members of civil rights organizations, trade unionists and students, marched through Harlem, NYC to protest the events in Selma. (NYT article)

March 15: President Johnson spoke to a joint session of Congress calling for a voting rights act. (NYT transcript of speech)

March 16, 1965: police clashed with 600 SNCC marchers.

March 17, 1965: despite their disagreements, SCLC Martin Luther King, Jr joined SNCC James Foreman in leading a march of 2000 people in Montgomery to the Montgomery County courthouse.

After the march, King announced a third Selma-to-Montgomery march. The City of Montgomery officials apologized for the assault on SNCC protesters by county and state law enforcement and asked King and Forman to work with them on how best to deal with future protests in the city; student leaders promised they would seek permits for future protest marches. Gov. Wallace continued to arrest protestors who ventured on to state-controlled property.

March 18, 1965: a federal judge ruled that SCLC had the right to march to Montgomery, AL to petition for ‘redress of grievances’.

March 20, 1965: President Lyndon B. Johnson notified Alabama’s Governor George Wallace that he would use federal authority to call up the Alabama National Guard in order to supervise the planned civil rights march from Selma to Montgomery.

MLK Jr Montgomery March

Third attempt

March 22, 1965: 3,200 civil rights demonstrators, led by the Reverend Martin Luther King, Jr., and under protection of a federalized National Guard, began a third attempt at a week-long march from Selma, Alabama, to the state capitol at Montgomery in support of voting rights.

March 22, 1965: 3,200 civil rights demonstrators, led by the Reverend Martin Luther King, Jr., and under protection of a federalized National Guard, began a third attempt at a week-long march from Selma, Alabama, to the state capitol at Montgomery in support of voting rights.

March 25, 1965: after four days and nights on the road, 25,000 were refused permission to give a petition to Governor Wallace. The petition read: “We have come not only five days and 50 miles but we have come from three centuries of suffering and hardship. We have come to you, the Governor of Alabama, to declare that we must have our freedom NOW. We must have the right to vote; we must have equal protection of the law and an end to police brutality.”

During the rally that followed the refusal by the Governor of Alabama, Governor Wallace. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. stated “We are not about to turn around. We, are on the move now. Yes, we are on the move and no wave of racism can stop us.” The speech became known as the “How long? Not Long” speech or as, “Our God is Marching On.” (text of speech)

MKL Jr Montgomery March

Viola Liuzzo

Viola Liuzzo had come from Michigan to participate in the protest. After King’s speech in Montgomery, she helped drive some of the marches back to Selma. On the way a car pulled up beside her. Someone in the car shot and killed her. See Liuzzo for her sad story.

On August 6, 1965, after a long often bitter Congressional fight, President Johnson signed the Voting Rights Act of 1965 guaranteeing African Americans the right to vote. The bill made it illegal to impose restrictions on federal, state and local elections that were designed to deny the vote to blacks., making it easier for Southern blacks to register to vote. Literacy tests, poll taxes, and other such requirements that were used to restrict black voting were made illegal.

MLK Jr Montgomery March

We Know the March Is Not Yet Over

March 7, 2015: President Obama and a host of political figures from both parties came to Selma to reflect on how far the country had come and how far it still had to go.

Fifty years after peaceful protesters trying to cross a bridge were beaten by police officers with billy clubs, shocking the nation and leading to passage of the landmark Voting Rights Act of 1965, the nation’s first African-American president led a bipartisan, biracial testimonial to the pioneers whose courage helped pave the way for his own election to the highest office of the land.

But coming just days after Mr. Obama’s Justice Department excoriated the police department of Ferguson, Mo., as a hotbed of racist oppression, even as it cleared a white officer in the killing of an unarmed black teenager, the anniversary seemed more than a commemoration of long-ago events on a black-and-white newsreel. Instead, it provided a moment to measure the country’s far narrower, and yet stubbornly persistent, divide in black-and-white reality. [NYT article]