Linda Carol Brown

February 20, 1943 – March 25, 2018

Linda Brown lived in Topeka, Kansas with her parents and two younger sisters. Topeka, like many American school districts, had separate schools for their black children and white children so Linda was not allowed to attend Sumner School, the nearest school, but for whites only.

She later said: “We lived in a mixed neighborhood but when school time came I would have to take the school bus and go clear across town and the white children I played with would go to this other school,”

Oliver Brown, Linda’s dad, decided to enroll his daughter in Sumner. He walked her there, spoke to the principal who not surprisingly refused to admit Linda, not for any academic or classroom space reasons, but simply because Linda was black.

Oliver and Leola Brown decided to do something.

Linda Carol Brown

US history of legal apartheid

19th century

The judicial history of US Courts ruling that African-American were not entitled to the same rights and privileges as other Americans is a long one.

In the 1857 decision in Dred Scott, Plaintiff in Error v. John F. A. Sanford, the Supreme Court held that Blacks, enslaved or free, could not be citizens of the United States. Chief Justice Taney, arguing from the original intentions of the framers of the 1787 Constitution, stated that at the time of the adoption of the Constitution, Black people were considered a subordinate and inferior class of beings, “with no rights which the White man was bound to respect.”

In 1865, following the Civil War, many state governments passed laws designed to marginalize its blacks using Black Codes. These laws imposed severe restrictions such as prohibiting the right to vote, forbidding Black from sitting on juries, and limiting their right to testify against white men. They were also forbidden from carrying weapons in public places and working in certain occupations.

The Civil Rights Act of 1866 guaranteed Blacks basic economic rights to contract, sue, and own property, but enforcement was rare.

In 1868, the ratification of the 14th amendment overruled the Dred Scott decision. The amendment’s Section 1 reads: All persons born or naturalized in the United States and subject to the jurisdiction thereof, are citizens of the United States and of the State wherein they reside. No State shall make or enforce any law which shall abridge the privileges or immunities of citizens of the United States; nor shall any State deprive any person of life, liberty, or property, without due process of law; nor deny to any person within its jurisdiction the equal protection of the laws.

But on April 14, 1873, the US Supreme Court decided in the Slaughterhouse cases that a citizen’s “privileges and immunities,” as protected by the Constitution’s Fourteenth Amendment against the states, were limited to those spelled out in the Constitution and did not include many rights given by the individual states.

Congress passed the Civil Rights Act of 1875 which prohibited discrimination in places of public accommodation, but on December 15, 1883, the US Supreme Court ruled that The Thirteenth and Fourteenth Amendments did not empower Congress to safeguard blacks against the actions of private individuals. To decide otherwise would afford blacks a special status under the law that whites did not enjoy.

The Court continued to uphold the legality of discrimination with its 1896 Plesy v Ferguson decision that held that separate but equal facilities for White and Black railroad passengers did not violate the Equal Protection Clause of the 14th Amendment.

In 1899, in Cumming v. Board of Education of Richmond County, State of Georgia, the Supreme Court upheld a local school board’s decision to close a free public Black school due to fiscal constraints, despite the fact that the district continued to operate two free public white schools.

20th century

Linda Carol Brown

In 1908, in Berea College v. Commonwealth of Kentucky, the Supreme Court upheld a Kentucky state law forbidding interracial instruction at all schools and colleges in the state.

In 1927, in Gond Lum v Rice, the Supreme Court held that a Mississippi school district may require a Chinese-American girl to attend a segregated Black school rather than a White school.

Linda Carol Brown

Crumbs of progress

On December 12, 1938, in the State of Missouri ex rel. Gaines v. Canada, the Supreme Court decided in favor of Lloyd Gaines, a Black student who had been refused admission to the University of Missouri Law School. The decision did not mean separate but equal was unconstitutional. It was because there was no Black law school that the Court based its decision for Gaines.

10 years later on January 12, 1948, in Sipuel v. Board of Regents of University of Oklahoma, a unanimous Supreme Court held that Lois Ada Sipuel could not be denied entrance to a state law school solely because of her race.

On June 5, 1950, in Sweatt v Painter: the Supreme Court held that the University of Texas Law School must admit Herman Sweatt, a Black student. The University of Texas Law School was far superior in its offerings and resources to the separate Black law school, which had been hastily established in a downtown basement.

Linda Carol Brown

Stage set

And so under the auspices of the Topeka NAACP, on February 28, 1951 Brown v. Board of Education was filed in Federal district court, in Kansas. The plaintiffs were thirteen Topeka parents on behalf of their 20 children. The case listed the plaintiffs names alphabetically and Brown came first. Brown was Oliver, Linda’s father. The ohter 12 plaintiffs were: Darlene Brown, Lena Carper, Sadie Emmanuel, Marguerite Emerson, Shirley Fleming, Zelma Henderson, Shirley Hodison, Maude Lawton, Alma Lewis, Iona Richardson, and Lucinda Todd, each a parent and representing 20 children.

In August, a three-judge panel at the U. S. District Court unanimously held that “no willful, intentional or substantial discrimination” existed in Topeka’s schools. The U. S. District Court found that the physical facilities in White and Black schools were comparable and that the lower court’s decisions in Sweatt v. Painter and McLaurin only applied to graduate education.

The NAACP appealed that decision and in June 1952 the Supreme Court announced that it would hear oral arguments in Briggs and Brown during the upcoming October 1952 term.

Briggs was a similar case and was “bundled” with Brown. Actually the case of Brown v. Board of Education as heard before the Supreme Court combined five cases: Brown itself, Briggs, Davis v. County School Board of Prince Edward County (filed in Virginia), Gebhart v. Belton (filed in Delaware), and Bolling v. Sharpe (filed in Washington, D.C.). All were NAACP-sponsored cases.

The case was argued for the states in early December 1952. Politicking by some justices in an attempt to get a unanimous decision in favor of Brown caused a delay, so it wasn’t until December 1953 that the NAACP’s Thurgood Marshall presented the case for the plaintiffs.

Linda Carol Brown

May 17, 1954

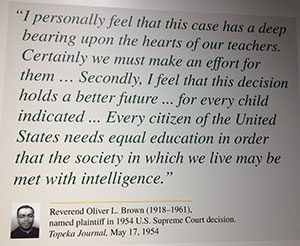

The Court delivered its unanimous decision in favor of the plaintiffs and in its decision said in part:

Does segregation of children in public schools solely on the basis of race, even though the physical facilities and other “tangible” factors may be equal, deprive the children of the minority group of equal educational opportunities? We believe that it does. …

“Segregation of white and colored children in public schools has a detrimental effect upon the colored children. The effect is greater when it has the sanction of the law, for the policy of separating the races is usually interpreted as denoting the inferiority of the negro group. A sense of inferiority affects the motivation of a child to learn. Segregation with the sanction of law, therefore, has a tendency to [retard] the educational and mental development of negro children and to deprive them of some of the benefits they would receive in a racial[ly] integrated school system.” …

We conclude that, in the field of public education, the doctrine of “separate but equal” has no place. Separate educational facilities are inherently unequal. Therefore, we hold that the plaintiffs and others similarly situated for whom the actions have been brought are, by reason of the segregation complained of, deprived of the equal protection of the laws guaranteed by the Fourteenth Amendment.

Linda Carol Brown

Linda later

By May 1954, Linda Brown was in middle school and in Topeka the upper grades had already been integrated.

From Wikipedia: Throughout her life, Brown continued her advocacy in the cause of equal access to education in Kansas. Brown worked as a Head Start teacher and a program associate in the Brown Foundation. She was a public speaker and an education consultant…

In 1979, with her own children attending Topeka schools, Brown reopened her case against the Kansas Board of Education, arguing that segregation continued. The appeals court ruled in her favor in 1993.

Linda Carol Brown

Death

When she died in 2018, Kansas Governor Jeff Colyer tweeted: “Sixty-four years ago a young girl from Topeka brought a case that ended segregation in public schools in America. Linda Brown’s life reminds us that sometimes the most unlikely people can have an incredible impact and that by serving our community we can truly change the world.”

2017 video with Linda’s sister, Cheryl Brown Henderson, speaks about modern educational inequality. She is a part of the Brown Foundation. whose “ mission is to build upon the work of those involved in the Brown decision, to ensure equal opportunity for all people. Our cornerstone is to keep the tenets and ideals of Brown relevant for future generations through programs, preservation, advocacy and civic engagement.”