Elizabeth Jennings Refused

July 16, 1854

We know the name Rosa Parks and her refusal to give up her seat in 1955. We are less likely to know the name Irene Morgan and her refusal in 1944. Nor Sarah Keys‘s refusal in 1954 nor Claudette Colvin‘s or Aurelia Browder‘s in 1955 before Rosa Parks.

What about the 19th century? Before there were busses, there were street cars.

Elizabeth Jennings Refused

Third Avenue Railroad Company

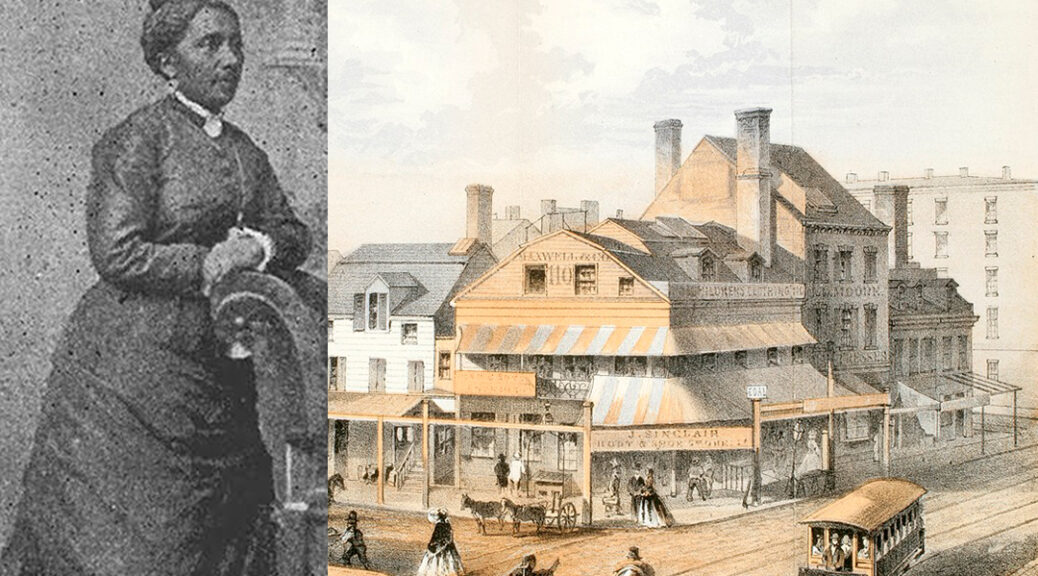

In July 1853, the Third Avenue Railroad Company began a streetcar service consisting of carriages pulled along these rails by horses. Passengers could board or leave the carriages at various points along the route. Some carriages carried a placard “Colored Persons Allowed,” but these carriages ran infrequently and African-Americans were often permitted to board the general streetcars at the discretion of the driver and conductor, provided none of the other passengers objected.

Elizabeth Jennings Refused

Elizabeth Jennings

Elizabeth Jennings lived in New York City and on July 16, 1854 the 24-year-old Black schoolteacher was on her way with friend Sarah Adams to the First Colored American Congregational Church on Sixth Street near the Bowery, where she was an organist. She boarded a Third Avenue Railroad Company horse-car at Pearl and Chatham Streets in lower Manhattan. Soon after boarding, the conductor ordered them to get off and wait for a car that served African American passengers.

Jennings refused, but with the assistance of police, the conductor succeeded in forcefully removing Adams and Jennings.

“I told him . . . I was a respectable person, born and raised in New York . . . and that he was a good for nothing impudent fellow for insulting decent persons while on their way to church,” she later said, according to a 2005 New York Times article.

“The conductor undertook to get her off, first alleging the car was full, when that was shown to be false. He pretended the other passengers were displeased at her presence. But [when] she insisted on her rights, he took hold of her by force to expel her. She resisted. The conductor got her down on the platform, jammed her bonnet, soiled her dress and injured her person. Quite a crowd gathered. But she effectually resisted. Finally, after the car had gone on further, with the aid of a policeman they succeeded in removing her.” — New York Tribune, February 1855

Elizabeth Jennings Refused

Church/Newspapers

That same NYT article stated, Her father, Thomas L. Jennings, was a prominent tailor who helped found both a society that provided benefits for black people and the Abyssinian Baptist Church, which later moved to Harlem.

The daughter had worked in black schools co-founded by a “conductor” of the Underground Railroad. Her own church — First Colored American — was a place of learning and political rebellion, where, one evening in 1854, addresses on God and the Bible alternated with talks on “The Duty of Colored People Towards the Overthrow of American Slavery” and “Elevation of the African Race.”

She wrote a letter that was read in church the next day. Parishioners forwarded the letter to The New York Daily Tribune, whose editor was famous abolitionist Horace Greeley, and to Frederick Douglass’s Paper. Both reprinted it in full.

Chester Arthur

Mr Jennings hired a young lawyer. Chester Arthur, who would become President of the United States in 1881 upon the assassination of James Garfield.

Arthur won. Judge William Rockwell of the Brooklyn Circuit Court ruled: “Colored persons if sober, well behaved and free from disease, had the same rights as others and could neither be excluded by the rules of the company, nor by force or violence.”

The all-male, all-white jury found for the plaintiff and awarded her damages of $225. She was also awarded $22.50 in costs. More importantly, the Third Avenue Railroad Company agreed to the immediate desegregation of its streetcar service.

Elizabeth Jennings Refused

Legacy

Other streetcar companies, however, retained segregated services and Thomas Jennings founded the Legal Rights Association to challenge racial segregation in public transportation. By 1861, all New York public transit was desegregated.

The importance of Elizabeth Jennings’s case is two-fold: The strategy of the Legal Rights Association became a model for later civil rights organizations through its use of public-opinion campaigns, lobbying, civil disobedience and litigation to effect change. [NY Courts site]

Elizabeth Jennings Refused

Honored

Elizabeth Jennings married and had a son; she ran a school for black children and died in 1901. She’s buried in Cypress Hills Cemetery in Brooklyn, but her name lives on with this City Hall street sign.

In New York City,only five female historical figures were depicted in statues in outdoor public spaces, according to She Built NYC, a city effort to expand representation of women in public art and monuments. All of those statues were in Manhattan, like the sculpture of Eleanor Roosevelt in Riverside Park and the bronze of Harriet Tubman in Harlem.

On March 6, 2019, the City announced that four more female historical figures would be honored with statues in New York. The announcement followed a months-long process seeking to fix what New York’s first lady, Chirlane McCray, called a “glaring” gender imbalance in the city’s streets and parks.

The four women — Billie Holiday, Helen Rodríguez Trías, Katherine Walker , and

…Elizabeth Jennings.

The city will place the statues in the boroughs they once called home.