June 21, 1927 – July 4, 1963

Clyde Kennard was born in Hattiesburg, Mississippi. When he was 12, he moved to Chicago to attend school. He graduated from Wendell Phillips High School.

He joined the military in 1945 and served in both Germany and Korea until 1952 when he was honorably discharged.

Activist Clyde Kennard

Furthering education

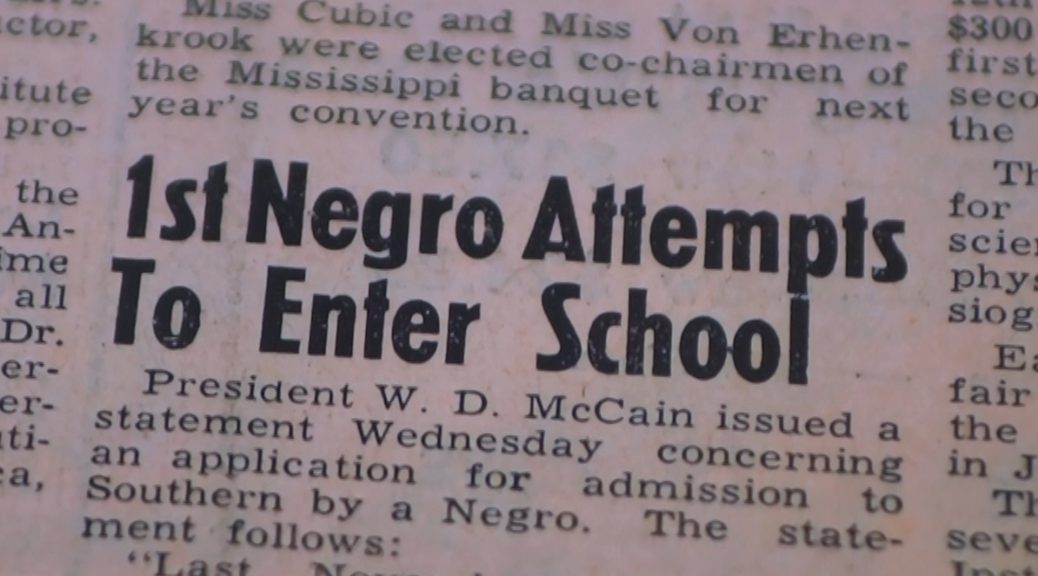

After the war, he returned to Chicago and completed three years of study at the University of Chicago. In 1955, Kennard returned to Hattiesburg to help care for his mother and run the family farm. Kennard wanted to complete his college education, so he sought to enroll at the all-white Mississippi Southern College, now the University of Southern Mississippi.

In 1955, Clyde Kennard attempted to enroll in Mississippi Southern College, an all-white public university in Hattiesburg. His credentials met the criteria for admission, but the university denied his application on the ground that he had been unable to provide references from five alumni in his home county.

In actuality, of course, it was because he was black.

Continued attempts

In 1958, Kennard argued that “merit be used as a measuring stick rather than race. We believe that for men to work together best, they must be trained together in their youth. We believe that there is more to going to school than listening to the teacher and reciting lessons. In school one learns to appreciate and respect the abilities of the other.”

On December 6, 1958, Kennard published a letter in the Hattiesburg American newspaper. He argued that “merit be used as a measuring stick rather than race. We believe that for men to work together best, they must be trained together in their youth. We believe that there is more to going to school than listening to the teacher and reciting lessons. In school one learns to appreciate and respect the abilities of the other.”

In response, the Mississippi Sovereignty Commission – a state agency formed to protect segregation – hired investigators to research Kennard’s background and uncover details that could be used to discredit him; these attempts were unsuccessful.

Kennard withdrew his application after Mississippi Governor James P. Coleman met personally with him to convince him to desist from applying to Mississippi Southern.

Activist Clyde Kennard

Framed

Kennard did not give up and reapplied in August 1959, threatening to take up the derailment of his application in federal court. He was again rejected on a technicality.

On September 15, 1959, the college president again rejected Kennard’s application on a technicality. Leaving the meeting, constables Charlie Ward and Lee Daniels arrested Kennard for reckless driving.

Ward and Daniels claimed before Justice of the Peace T. C. Hobby to have found five half pints of whiskey, along with other liquor, under the seat of Kennard’s car. Mississippi was a “dry” state, and possession of liquor was illegal.

Shortly afterward, on September 25, the Hattiesburg American published another letter Kennard wrote. In it he wrote, ““[W]e have no desire for revenge in our hearts. What we want is to be respected as men and women, given an opportunity to compete with you in the great and interesting race of life. We want your friends to be our friends; we want your enemies to be our enemies; we want your hopes and ambitions to be our hopes and ambitions, and your joys and sorrows to be our joys and sorrows.”

Activist Clyde Kennard

Convicted

Kennard was convicted and fined $600. He soon became the victim of an unofficial local economic boycott (also a tactic of the Sovereignty Commission), which cut off his credit.

All these claims were false, of course, and were meant to keep Kennard from continuing to apply to the university.

It didn’t. Kennard continued his attempts to register at Mississippi Southern.

Activist Clyde Kennard

Imprisoned

On January 23, 1960, after his third attempt to enter the college and his arrest on bogus charges, Kennard was still not ready to give up the fight. He wrote to the editor that he had “done all that is within my power to follow a reasonable course in this matter… I have tried to make it clear that my love for the State of Mississippi and my hope for its peaceful prosperity is equal to any man’s alive. The thought of presenting this request before a Federal Court for consideration, with all the publicity and misrepresentation which that would bring about, makes my heart heavy. Yet, what other course can I take?”

He was arrested again on September 25, 1960 with an alleged accomplice for the theft of $25 worth of chicken feed from the Forrest County Cooperative warehouse. Kennard went to trial, with the accomplice, Johnny Lee Roberts, testifying that Kennard paid him to steal the feed.

On November 21, 1960, an all-white jury deliberated 10 minutes and found Kennard guilty. He was convicted and sentenced to seven years at Parchman Penitentiary.

Speaking at a rally in support of his friend, the NAACP activist Medgar Evers broke down in tears as he described the “mockery of judicial justice” in Kennard’s case.

Activist Clyde Kennard

Cancer

He was diagnosed with colon cancer in prison, but he was refused treatment and forced to continue working in the fields despite his weakened physical state.

Only after Evers, Martin Luther King Jr., and others threatened to accuse the State of Mississippi of murder was the emaciated and terminally ill Kennard released. Dick Gregory paid for him to undergo treatment in Chicago. But it was too late to save the man who wanted a college degree. Kennard died on July 4, 1963, less than a month after his friend, Medgar Evers, was murdered.

Activist Clyde Kennard

Revelations

In 1991 the Clarion-Ledger newspaper in Jackson, Mississippi published previously secret documents from the files of the Mississippi State Sovereignty Commission, showing that Kennard had been framed.

In 2005 Jerry Mitchell, an investigative reporter for the Clarion-Ledger interviewed the black witness who, as a teenager, had testified against Kennard. The man admitted that Kennard had “nothing to do with the stealing of the chicken feed.”

[From the Americas Who Tell the Truth site} Kennard’s case came to the attention of a high school teacher in Chicago. Barry Bradford and his students teamed up with Steve Drizin, the Director of the Center on Wrongful Convictions at Northwestern University’s School of Law, LaKeisha Bryant the president of the Afro-American Student Association at the University of Southern Mississippi, Dr. Joyce Ladner and Raylawni Branch, the woman who had served Kennard coffee on his way to apply to Mississippi Southern the third time and had gone on to an impressive career of her own.The team documented the case in favor of Kennard, discovered the legal arguments that could get the case back into court, and began to apply public pressure with the help of the former federal judge from Mississippi, Charles Pickering.

Finally, on May 16, 2006, the case that Steve Drizin called, “one of the saddest of the civil rights era because he was silenced by ‘respectable’ people – academics, politicians, lawyers, prosecutors, judges, businessmen – all acting under the ‘color of law,'” finally ended up in the same court where the 33-year-old Clyde Kennard had been convicted. The presiding judge at the Circuit Court of Forrest County, Robert Helfrich declared, “It is a right-wrong issue. To correct that wrong I’m compelled to do the right thing and declare Mr. Kennard innocent.”