George Whitmore Jr Crucified

We seem to differentiate the mistreatment and torture of the enslaved from the miscarriage and misuse of justice when slavery constitutionally ended. I don’t know why. It seems to me such wrongs need no differentiation.

The story of George Whitmore, Jr is a long one. One that is difficult to read. We keep hoping someone will stop the story, but it keeps going and going and going.

In our eagerness to solve a mystery and ease our pain, we too often create a truth and point a finger at a person. We say “Did it. They are guilty.”

We make an arrest. We have a trial. We find the alleged guilty. We will allow local, state, and federal appeals, but we will put them to death or sentence them to die imprisoned.

That was the sentence we gave to George Whitmore, Jr. An innocent man.

George Whitmore Jr Crucified

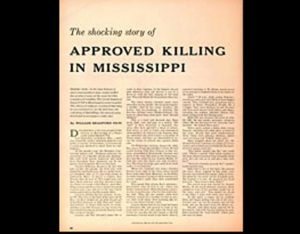

Career Girl murders

August 28, 1963: Janice Wylie, a 21-year-old Newsweek magazine researcher and summer stock actress, and Emily Hoffert, a 23-year-old teacher, were stabbed to death in the apartment they shared at 57 E. 88th Street in Manhattan; Wylie was raped. Wylie is the daughter of Max Wylie, a New York novelist, playwright, and advertising executive. Hoffert is the daughter of a Minneapolis surgeon. The media will call it the Career-Girl Murders. George Whitmore, Jr listened to Kin’g speech in his Wildwood, NJ home. In seven months, Whitmore, an African-American drifter with a limited IQ, will be picked out of a photo lineup by a woman who had been assaulted.

August 30, 1963: Newsweek offered a $10,000 reward for the arrest and conviction of the murderer or murderers.

George Whitmore Jr Crucified

Minnie Edmonds

April 14, 1964: Minnie Edmonds, a 46-year-old African American cleaning woman and mother of five, was stabbed to death by a man who attempted to snatch her purse near Sutter Avenue and Chester Street in the Brownsville section of Brooklyn.

George Whitmore Jr Crucified

Elba Borrero

April 23, 1964: Elba Borrero, a 21-year-old Puerto Rican practical nurse, was assaulted at 1:15 a.m. in what she described as an attempted purse-snatching in Brownsville. NYPD Patrolman Frank Isola heard Borrero scream and ran to the scene. He fired four warning shots at the fleeing assailant. Police Sergeant Thomas J. Collier interviewed Borrero and wrote a report describing the assailant as “an unnamed Negro” and the crime as an attempted purse-snatching. Borrero gave a button that she had ripped off the assailant’s coat to the police after the assault, Patrolman Frank Isola encountered George Whitmore Jr. on the street, but concluded that Whitmore was shorter and thinner than the man he saw running from the scene.

George Whitmore Jr Crucified

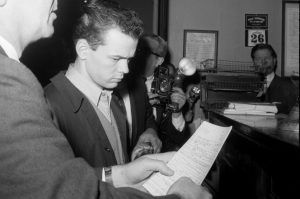

George Whitmore

April 24, 1964: cruising Brownsville, NYPD Patrolman Frank Isola and Detective Richard Aidala spotted Whitmore and, despite the discrepancy between his appearance and that of the assailant Isola had seen, took Whitmore to the 73d Precinct station for questioning. After Detective Aidala called Elba Borrero and told her a suspect was in custody, she viewed Whitmore through a peephole in a door and said Whitmore was the man who tried to rape her. (This was the first mention of attempted rape.) Whitmore had in his possession a photograph of a young white woman whom Detective Edward Bulger identified as Janice Wylie.

April 25, 1964: after 26 hours of interrogation, George Whitmore, Jr., a 19-year-old eighth-grade dropout with a 90 IQ, signed a 61-page confession admitting to

a) the murders of Wylie, Hoffert; (see May 6)

b) the murder of Minnie Edmonds; (see April 28)

c) attempted rape of Elba Borrero. (see May 6)

April 28, 1964: Whitmore indicted in for the Minnie Edmonds murder. His court-appointed attorney, Jerome Leftow, stated that Whitmore had repudiated the confessions, claiming he was beaten during interrogation, and would like to take a lie-detector test.

May 5, 1964: Whitmore indicted in Kings County for the attempted rape and assault of Elba Borrero.

May 6, 1964: Whitmore indicted in New York County for the Wylie-Hoffert crime.

George Whitmore Jr Crucified

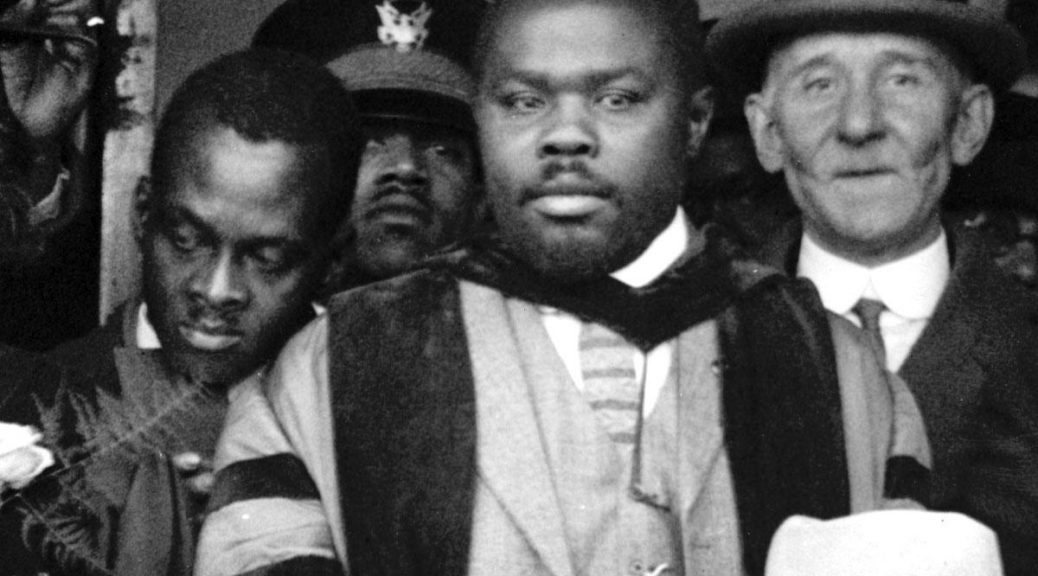

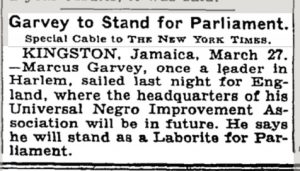

Richard Robles

October 31, 1964: Police disclosed that they were questioning another unidentified suspect in the Wylie-Hoffert case. The suspect was identified as a white 19-year-old narcotics addict who had a record of burglary and sexual assault. (Evidently the suspect was Richard Robles, although Robles is not 19 but in his early 20s.

November 9, 1964: Whitmore’s trial for the attempted rape and assault of Borrero opened in Brooklyn. (When a defendant faces trials for more than one crime, it is a common tactic of prosecutors to try the least serious case first so that, if convicted, the defendant will have a criminal record when he goes to trial for a more serious crime. This will discourage the defendant from taking the stand in the latter trial. If the defendant nonetheless chooses to testify, the prior conviction may be used for impeachment purposes on cross examination. It also may be used against the defendant at sentencing.)

George Whitmore Jr Crucified

Whitmore convicted

November 18, 1964.: Whitmore convicted by a jury before Brooklyn Supreme Court Justice David L. Malbin of the Elba Borrero assault and attempted rape, but Malbin delayed sentencing pending Whitmore’s trial for the Wylie-Hoffert murders.

January 22, 1965: The New York Times quoted Stanley J. Reiben, George Whitmore, Jr.’s pro bono lawyer, as saying that the photo found in Whitmore’s possession was not a photo of Wylie but of a women named Arlene Franco, who lived in Wildwood, N.J.

January 26, 1965: Richard “Ricky” Robles, a white 22-year-old narcotics addict, charged with the Wylie-Hoffert crime. While not dismissing the indictment against George Whitmore, Jr., New York County DA Frank S. Hogan presented a 1,400-word recommendation that Whitmore be released on his own recognizance. The document seemed to absolve Whitmore of the crime, as did a statement Hogan released to the press. Says the latter, “In spite of every safeguard, occasional honest mistakes are made. To eliminate even this minute fraction of error is the ceaseless effort of those entrusted with the administration of justice.” Hogan’s recommendation that Whitmore be released was accepted, although it was a meaningless gesture, given that Whitmore was being held pending sentencing for the Borrero crime and pending trial for the Edmonds murder.

January 27, 1965: The New York Times quotes an unnamed assistant to NY County DA Frank Hogan as saying, “I am positive that the police prepared the confession for George Whitmore, Jr., just as his lawyer charged a few days ago. I am also sure that the police were the ones who gave Whitmore all the details of the killings that he recited to our office.”

January 29, 1965: Kings County DA Aaron E. Koota met with five representatives of the Brooklyn N.A.A.C.P. who demand that he dismiss the indictment against Whitmore for the Minnie Edmonds murder. Koota refused and told the press that Whitmore’s “guilt or innocence of this crime should be determined by a jury based on all the evidence in the case.”

January 30, 1965: The New York Times published an editorial praising both Stanley J. Reiben (Whitmore’s lawyer) and Frank Hogan (NY prosecutor) for acting “in the highest tradition of the bar.” The editorial said that the case “provokes fresh doubt” about the validity of the death penalty and urged its abolition.

February 1, 1965: Whitmore’s former attorney, Jerome Leftow, and one of this current attorneys, Arthur H. Miller, revealed that Whitmore had been given “truth serum” (sodium amytal) at Bellevue Hospital and, while under the influence of the drug, had consistently maintained his innocence. The N.A.A.C.P. and ACLU asked Governor Nelson Rockefeller and FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover to investigate the circumstances that led to Whitmore’s false confession in the Wylie-Hoffert case.

February 2, 1965: a U.S. Justice Department spokesperson said the department was “following the situation closely.”

George Whitmore Jr Crucified

Governor Nelson Rockefeller

February 4, 1965: NY Governor Nelson Rockefeller refused the NAACP’s demand for an investigation. The Governor stated that he had “no jurisdiction over the courts and therefore it would be inappropriate to seek to intervene in matters pending before them.”

Whitmore’s attorney, Stanley J Reiben, filed an affidavit opposing a blue-ribbon jury. Reiben said that such a jury would be a “lily-white all-male” jury, which would enhance “the conviction ration of the District attorney.”

George Whitmore Jr Crucified

Stanley J Reiben

February 11, 1965: Whitmore’s attorney, Stanley J Reiben filed a motion asking Justice Malbin to set aside George Whitmore, Jr.’s conviction in the Elba Borrero attempted rape/robbery case on the grounds that police lacked probable cause to arrest Whitmore and that his confession, therefore, whether voluntary or involuntary, should have been suppressed at the trial. The motion stated that Detective Aidala had testified before the grand jury that he had arrested Whitmore on a Brooklyn street — a concession that police lacked probable cause.

The motion also stated that, in an unrelated case, Detective Edward Bulger (the detective who had incorrectly said the picture Whitmore had in his possession was one of the murdered Janice Wylie) had obtained a confession from 22-year-old David Coleman to the 1960 murder of a 77-year-old woman in Brooklyn — a crime for which Coleman is on death row.

February 14, 1965: District Attorney Aaron E Koota agreed to reopen the David Coleman case.

George Whitmore Jr Crucified

Richard Robles indicted

February 15, 1965: Richard Robles indicted for the Wylie/Hoffert murders. Robles "maintains his innocence," according to his court-appointed attorney.

George Whitmore Jr Crucified

Stanley J Reiben

February 17, 1965: Whitmore’s attorney, Stanley J Reiben, said that he had covered the route supposed to have been followed by Whitmore before the attack on Elba Borrero and stated that Whitmore “would have to have a vehicle or be an Olympic runner” to get from his former girl friend’s house to an elevated subway station seven blocks away, follow Borrero back from the station nearly five blocks to her home, attack her, and run away.

March 1, 1965: Gerald Corbin, a juror in the Elba Borrero case, testified at a hearing before Justice Malbin on the motion for a new trial that “practically everyone” on the jury knew that George Whitmore, Jr. had been charged with the Wylie-Hoffert crime. According to Corbin, one of his fellow jurors had stated, “This is nothing compared to what he is going to get in New York.”

Corbin also testified that at least one juror “on more than one occasion” used racial slurs referring to the sexual proclivities of Negroes and Puerto Ricans. “Whitmore,” said the juror in question, “was guilty of attempted rape because Negros are “like jackrabbits” and “got to have their intercourse all the time.” An FBI report, which the prosecution had withheld at the trial, was introduced at the hearing. It stated that the button Borrero ripped from her assailant’s coat differed in size and color from the buttons on the tan poplin raincoat Whitmore was wearing when he was taken into custody.

George Whitmore Jr Crucified

District Attorney Aaron Koota

March 2, 1965: District Attorney Aaron Koota conceded that George Whitmore, Jr. deserved a new trial in the Borrero case, but Justice Malbin reserved ruling.

March 3, 1965: At a hearing before Justice Dominic S. Rinaldi, before whom the Minnie Edmonds case was pending, defense lawyers moved to suppress Whitmore’s confession on the ground that police lacked probable cause to arrest him and that, in any event, the confession was unworthy of belief in view of Whitmore’s false confession in the Wylie-Hoffert case.

On the probable cause issue, Detective Richard Aidala testified that he erred when he told the grand jury that he had arrested Whitmore on the street. In fact, Aidala asserted, he merely asked Whitmore to go to the station, Whitmore “willingly agreed,” and the arrest was not made until Borrero identified Whitmore.

George Whitmore Jr Crucified

Patrolman Frank Isola

March 8, 1965: Patrolman Frank Isola testified before Justice Dominic Rinaldi that he did not arrest George Whitmore, Jr. upon their initial encounter, five hours after the Borrero assault, because Whitmore “did not appear to be same man” he had seen fleeing the scene.

March 9, 1965: Police Sergeant Thomas J. Collier, who took the initial report from Elba Borrero, testified that Borrero did not mention the attempted rape but rather alleged only that her assailant “attempted to take her pocketbook.”

March 19, 1965: NY Supreme Court Justice David L. Malbin found that the jury in the Elba Borrero case had been influenced by “prejudice and racial bias” and reversed George Whitmore, Jr.’s conviction, granting him a new trial. Malbin stated: “The hearing revealed that prejudice and racial bias invaded the jury room. Bigotry I any of its sinister forms is reprehensible, it must be crushed, never to rise again. It has no place in an American courts of Justice.”

On the same day, a bipartisan commission recommended the end of capital punishment in New York State.

George Whitmore Jr Crucified

DA Frank Hogan

March 25, 1965: DA Frank Hogan dismissed first-degree murder charges against two drifters — James Stewart, 24, and R. L. Douglas, 32 — who had been charged with the hammer-slaying of John Walshinsky, a derelict — a crime to which Stewart and Douglas confessed. The men said that the confessions were beaten out of them.

March 26, 1965: Justice Dominic Rinaldi ruled that Whitmore’s confession to the Minnie Edmonds murder was voluntary and admissible. Rinaldi chastises Whitmore’s attorney, Stanley Reiben, for “talking to the newspapers” about the case.

April 2, 196: The N.A.A.C.P. revealed that Detective Edward Bulger, in addition to his involvement in obtaining the dubious David Coleman confession (see Feb 11, 1965), also had been accused in another case of obtaining a confession by fraud from a man named Charles Everett. If Everett would admit the crime, Detective Bulger allegedly promised to intercede with the victim to work out a light sentence. The victim in fact was dead. Everett was convicted of murder, but his conviction was later reversed.

George Whitmore Jr Crucified

Blue-ribbon juries

April 6, 1965: The New York Assembly passed a bill to abolish blue-ribbon juries in New York City. Blue ribbon juries were established in the 1930s and are made up of persons selected on the basis of education and economic status.

April 12, 1965: Whitmore’s trial for the Minnie Edmonds slaying opened before an all-male blue-ribbon jury and Kings County Supreme Court Justice Dominic S. Rinaldi. (Blue-ribbon juries — criticized by liberal groups as self-righteous and conviction-prone — are composed of persons from high educational and economic levels and permitted in counties with more than a million population under a New York statute enacted in the 1930s.)

April 14, 1965: Detective Joseph Di Pima testified that George Whitmore, Jr.’s confessions were voluntary, telling the jury, “All I had to say to him was: “What happened next George?”

April 19, 1965: In view of the “the antipathy and antagonism” Justice Dominic Rinaldi had shown Whitmore’s attorney, Stanley Reiben, Reiben asked to withdraw from the case, saying he can no longer effectively represent his client. Rinaldi denied the request.

April 21, 1965: The prosecution rested in the Minnie Edmonds murder trial.

April 23, 1965: Whitmore testified that Detective Aidala and Patrolman Frank Isola beat him.

April 28, 1965: Prosecutor Sidney A. Lichtman told the jury that the Wylie-Hoffert indictment was still pending in Manhattan. Whitmore’s attorney, Stanley Reiben argued, “How can the Wylie-Hoffert confession be bad and the others good beyond a reasonable doubt, given the same day to the same detectives Is it possible for Wylie-Hoffert to be phony while the others are not?”

May 4, 1965: DA Frank Hogan formally dismissed the Wylie-Hoffert indictment pending against Whitmore.

May 5, 1965: DA Aaron Koota said his office would again try George Whitmore, Jr. for the Elba Borrero attempted assault and rape in Brooklyn.

George Whitmore Jr Crucified

Abolishing the death penalty

May 13, 1965: The New York Senate by a vote of forty-seven to nine approved a bill abolishing the death penalty for all murders except those of peace officers or prison guards and murders committed during an escape.

May 19, 1965: The New York Assembly passes the abolition bill by a vote of seventy-eight to sixty-seven.

May 22, 1965: The New York State Association of Trial Lawyers and the Northern New York Conference of the Methodist Church urged Governor Rockefeller to sign a bill that would virtually abolish capital punishment in the state.

May 26, 1965: Justice Vincent D. Damiani of Kings County Supreme Court granted a motion by Whitmore’s attorney, Stanley J Reiben, requiring DA Aaron Koota to bring Whitmore to trial for the Minnie Edmonds murder before retrying him for the lesser crime against Borrero. Damiani wrote, “To permit the defendant to be tried again on the lesser charge of attempted rape before his trial on the more serious indictment for murder will result in further publicity and substantially increase the difficulty in selecting an impartial jury in the murder case.”

June 1, 1965: NY Gov Nelson Rockefeller signed the abolition of death penalty bill.

June 3, 1965: DA Aaron Koota argued before George J. Beldock, presiding justice of the Appellate Division of the Supreme Court, that Justice Vincent Damiani had no authority to exert control over the prosecution calendar. Beldock directed Damiani to explain more fully why Whitmore should not be tried first for the Borrero case.

June 8, 1965: the Appellate Division unanimously held that Whitmore may be tried first in the Elba Borrero case.

July 15, 1965: Governor Nelson Rockefeller signed legislation abolishing blue-ribbon juries.

October 14, 1965: Richard Robles went on trial before a jury and New York County Supreme Court Justice Irwin D. Davidson for the Wylie-Hoffert murders.

October 18, 1965: Prosecutors disclose that friends of Richard Robles cooperated in the surreptitious recording of conversations in which he admitted the double murder. When confronted with the tapes after his arrest, Robles “freely and voluntarily confessed” in the presence of eight police officers, including Thomas J. Cavanagh Jr., the commander of the Manhattan detective squad.

George Whitmore Jr Crucified

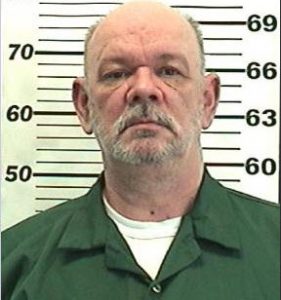

Richard Robles guilty

December 1, 1965: the jury found Richard Robles guilty. January 11, 1966: Justice Davidson sentenced Richard Robles to life in prison.

George Whitmore Jr Crucified

George Whitmore, Jr.’s retrial

March 22, 1966: George Whitmore, Jr.’s retrial for the attempted rape and assault of Elba Borrero opened before a Kings County jury and Supreme Court Justice Aaron F. Goldstein.

March 23, 1966: after Detective Richard Aidala testified that Whitmore’s confession to the Elba Borrero crime was voluntary, Whitmore’s attorney, Stanley Reiben asked, “Did anyone coerce or force him into making the Wylie-Hoffert confession?” Justice Aaron Goldstein immediately dismissed the jury and then upbraided Reiben for his “intemperate question.”

Out of the jury’s presence, Reiben labeled Aidala “the world’s biggest liar,” and asked Goldstein, “How can I achieve justice unless I can establish this?” Goldstein said he would reserve ruling on the admissibility of the evidence resulting to Whitmore’s confession in the Wylie-Hoffert case.

March 24, 1966: Justice Aaron Goldstein held evidence of the Wylie-Hoffert confession inadmissible. Whitmore’s attorney, Stanley Reiben waived further examination of witnesses, declaring that George Whitmore, Jr. cannot receive a fair trial absent the Wylie-Hoffert evidence. Both sides rest. (see Mar 25, 1966) March 25, 1966: Whitmore convicted for the second time in the Elba Borrero attempted rape and assault case.

May 27, 1966: Justice Aaron Goldstein sentenced Whitmore to five to ten years in prison for the attempted rape and assault. With time off for good behavior and credit for 25 months already served, Whitmore was eligible for release in 15 months.

June 13, 1966: in Miranda v. Arizona the US. Supreme Court holds that police must warn suspects of their rights to remain silent and consult with a lawyer before submitting to questioning.

June 30, 1966: on DA Aaron Koota’s motion, Kings County Supreme Court Justice Hyman Barshay dismissed the indictment against Whitmore in the Minnie Edmonds murder case.

July 12, 1966: Justice Hyman Barshay set bail at $5,000 for George Whitmore, Jr. pending appeal of his conviction in the Elba Borrero case.

George Whitmore Jr Crucified

Whitmore released

July 13, 1966: Whitmore was released two years, eleven weeks, and three days after his arrest — 810 days in all —on bail guaranteed by NYC AM radio station WMCA. R Peter Straus, the station’s president, agreed to put up the necessary collateral and said that he had been interested in the case, had often commented editorially on it, and was concerned about a poor man unable to make bail.

April 10, 1967: The Appellate Division of the Supreme Court reversed George Whitmore, Jr.’s conviction in the Borrero case and granted him yet another trial, holding that “under the peculiar circumstances of this case, it was prejudicial error for the trial court to refuse to allow cross examination with reference to all of the defendant’s statements to the police.”

April 13, 1967: DA Aaron Koota stated that “in the interests of justice” Whitmore will be tried a third time for the Elba Borrero crime.

May 15, 1967: Whitmore’s third trial opened before Justice Julius Helf and in Kings County Supreme Court and jury selection completed. In view of the Miranda ruling, the confession is inadmissible. The case now rests entirely on Elsa Borrero’s identification.

May 16, 1967: both sides rest in the third Whitmore trial for assault and attempted rape of Elba Borrero.

George Whitmore Jr Crucified

Whitmore guilty again

May 17, 1967: the jury returned a verdict of guilty. Whitmore was taken into custody for a psychiatric examination as required by state law. If he law did not so require, Justice Julius Helf stated, he would have continued Whitmore’s bail.

June 8, 1967: Whitmore again sentenced to five to ten years in prison.

June 15, 1967: Kings County Supreme Court Justice Philip M. Kleinfeld granted a motion to release George Whitmore, Jr. on $5,000 bail. The additional time he had spent in custody following his third conviction in the Elba Borrero case had added 395 days of incarceration to the 810 days he had served pending his first two trials and his first release on bail, bringing Whitmore’s total incarceration time to two years, fifteen weeks, and five days.

July 25, 1968: The Appellate Division held George Whitmore, Jr.’s latest appeal in abeyance pending a hearing before Justice Julius Helf on the validity of the in-court identification by Elba Borrero in view of the fact that her initial identification of him was at a one-man show-up through a peephole.

November 5, 1968: Eugene Gold was elected Brooklyn District Attorney to succeed Aaron Koota.

April 8, 1969: Justice Julius Helf upheld the validity of the identification, saying there was “an unmistakable ring of truth to her testimony.”

George Whitmore Jr Crucified

Supreme Court

July 28, 1970: The Supreme Court’s Appellate Division unanimously affirmed George Whitmore, Jr.’s third conviction in the Elba Borrero case.

September 24, 1970: New York Court of Appeals affirmed the conviction of Richard Robles in the Wylie-Hoffert case.

April 21, 1971: The New York Court of Appeals by a four-to-three vote upheld the Whitmore conviction without an explanatory opinion.

February 28, 1972: The U.S. the Supreme Court refused to disturb Whitmore’s conviction for the attempted rape and assault of a practical nurse Elba Borrero almost eight years earlier.

December 22, 1972: Brooklyn DA Eugene Gold announced he was reopening the case in view of an affidavit obtained by TV journalist Selwyn Raab from Elba Borrero’s sister, Celeste Viruet, who lived near Borrero at the time of the assault but had since returned to her native Puerto Rico. The affidavit stated that before Borrero identified George Whitmore, Jr. police had shown her a photo array and she had identified another person as her assailant.

George Whitmore Jr Crucified

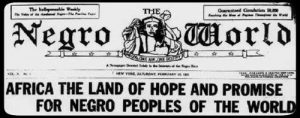

“The Marcus-Nelson Murders“

March 8, 1973: CBS aired “The Marcus-Nelson Murders,” a three-hour film based on the Wylie-Hoffert murders with Telly Savalas staring as Detective Lieutenant Theo Kojack (later shortened to Kojak) — a character loosely based on Detective Cavanagh, who had been instrumental in developing the evidence that the murders were committed not by George Whitmore, Jr. but by Richard Robles.

Leon Vincent, superintendent of Green Haven prison in upstate NY, permitted George Whitmore to go to the sick ward and watch the show in privacy.

George Whitmore Jr Crucified

Whitmore released a final time

April 10, 1973: NY Supreme Court Justice Irwin Brownstein released Whitmore from jail at the request of Brooklyn DA Eugene Gold based on “fresh new evidence” indicating that Borrero’s identification of him was suspect.” Gold told Brownstein, “If in fact he is guilty of these charges, surely his debt to society has been paid by his incarceration. If he is innocent, I pray that my action today will in some measure repay society’s debt to him.” He termed Whitman’s treatment by the law “a disgrace.” Justice Borwnstein stated, “It is indeed disgraceful that this defendant has been subjected to nine years of prosecution and appeals.” Whitmore’s most recent incarceration totaled 406 days, bringing his total time behind bars to 1,216 days.

April 16, 1979 : The NY Times reported that Whitmore’s $10 million claim against New York City for improper arrest and imprisonment and his request for a jury trial were dismissed for technical reasons the previous week by Justice William Bellard in State Supreme Court.

April 22, 1985: Stanley J. Reiben, chief defense attorney in the George Whitmore murder case, died at his home in Manhattan after a long illness. He was 70 years old.

November, 1986: Richard Robles, who had himself protested his innocence over the original double-murders, admitted his guilt to a parole board hearing. He had broken into the flat in order to obtain money for drugs and had assumed at first it was empty.

George Whitmore Jr Crucified

Richard Robles tells his story

October 2, 1988: The New York Times published an article by Selwyn Raab, who interviewed Richard Robles in light of a forthcoming pardon hearing. Raab quoted Robles as saying that he broke into the Wylie-Hoffert apartment believing no one was home. He was looking for money to support his $15-a-day heroin habit, but when he encountered Wylie he raped her. Then he bound her and was preparing to leave when Hoffert came home. He took $30 from her purse and bound her as well. As he again prepared to leave, Hoffert said, “I”m going to remember you for the police. You”re going to jail.” When she said that, Robles continued, “I just went bananas. My head just exploded. I got to kill. You”re mind just races and races. It’s almost like you”re not you.” He said he clubbed both women unconscious with pop bottles, then slashed and stabbed them with knives he found in their kitchen.

November 4, 1988: Richard Robles, who had served 24 years in the famous ”career girls” murder case, was denied parole for a second time. Mr. Robles, 45 years old, was given a life sentence for the killing of Janice Wylie, a Newsweek researcher, and Emily Hoffert, an elementary-school teacher, in an East Side apartment on Aug. 28, 1963.

August 29, 1993: Richard Robles, 50 years old, had served 29 years in prison, one of the longest sentences in the state penal system. The Parole Board, citing “the seriousness of the crime,” has denied him parole five times. Prison officials said that of the state’s 65,000 inmates, only 20 have been imprisoned longer than Mr. Robles.

October 8, 2012: Whitmore died in a Wildwood, N.J., nursing home. He was 68. In a NY Times Op-Ed article entitled, “Who Will Mourn George Whitmore?” T. J English wrote:

This week, a flawed but beautiful man who offered up his innocence to New York City died with hardly any notice. To those who benefited from his struggles or who believe the city is a fairer place for his having borne them, I ask: Who grieves for George Whitmore?

In recent months, I’d fallen out of touch with George Whitmore, Jr.. Knowing him, and attempting to assume a measure of responsibility for his life, was often exhausting. While I had come to love him, the drunken phone calls, the calls from hospital emergency rooms and flophouses, and the constant demands for money became overwhelming. When people who claimed to be friends of his starting calling me and asking for favors, I decided to back off. But when I received a cryptic e-mail from one of his nephews, informing me that Whitmore had died on Monday, I was overcome with sadness and regret.

February 28, 2014: from an article in The Paris Review by Sabine Heinlein. I mailed a copy of my book Among Murderers, about the struggles three men faced when they returned to the world after several decades behind bars, to Richard Robles.

Robles wrote back:

Remorse is a tough subject. It’s complicated by the human desire to avoid pain and punishment, which is actually stronger, I think. It includes feelings of shame and guilt. Then there’s the drive to rehabilitate oneself and change. It is complex and confusing. One has to take an honest look at himself and get rid of that “bullshit ego.”

He added:

I found it [the book] very honest and real. I think it will be an eye opener for those who have the misconception that parole is freedom. I’d like to see it as mandatory reading for all first offenders because they often think “parole is freedom” and are quickly, very negatively struck with profound disappointment when reality smacks or kicks them in the face.

Along these lines I would have liked to see more about the unrealistic expectations prisoners fantasize about in prison—and how fantasies inhibit reform/rehabilitation efforts. I think you tried to portray that but I’m not certain the average reader could get it. You portray a prisoner as saying “Expect the unexpected.” I’d rephrase that to “Expect to be disappointed in every dream you conjure in prison.”

George Whitmore Jr Crucified